In the previous article in this series, we realized how power was concentrated in the hands of a small clique from Gitararma and this progressively reduced the geographical base of President Gregoire Kayibanda’s PARMEHUTU party. Inequality in cabinet representation frustrated members of the military from the north. The beginning of the end of Kayibanda’s regime had begun as this piece will.

Massacre of the Tutsi in 1973 In 1972, President Kayibanda convened his closest friends in order to execute his divisive plan. It was aimed at chasing the Tutsi from schools and higher institutions as well as from all public and private establishments. He contended that this was aimed at achieving the objectives of the 1959 revolution.

The same explanation was used again in 1994, before and during Genocide against the Tutsi. Kayibanda and his friends put in place “committees of national interest” to execute the plan. Members of those committees were administrative agents, provincial governors, security agents and army officers.

Kayibanda used the Burundi crisis, which began in April 1972, as an opportunity and a pretext to realize his project. Mugesera tried to work out the chronology of events and made an inventory of the names of pupils/students and civil servants who were removed in all Rwanda’s provinces. In February 1973, the massacre of the Tutsis was organized.

Evidence to prove the above assertion abounds. Names of “undesirable” Tutsi civil servants were hung on notice boards on the same day, on the night of February 26-27, 1973. Orders for Tutsi to leave establishments were formulated everywhere in the same manner.

No province was spared and all Tutsi were affected. There was no government official, head of school, state or parastatal institution that officially approved the above act. Everybody kept silent.

The government and its sympathizers argued that the Hutu could no longer tolerate being a minority in schools and other establishments when they were demographically the majority. To that effect, the Rwandan Ambassador to Belgium said: “More than ten years after the Hutu revolution (..

.), enterprises employ only Tutsi. In universities, 65 per cent of the students are Tutsi.

The majority of the teaching staff is Tutsi. In government, almost all high-level civil servants are Tutsi. The majority of the clergy are Tutsi.

All this shows that the government has never pursued an aggressive policy against Tutsi.” However, a study conducted by the Ministry of Secondary and Higher Education put the percentage of Tutsi students in secondary schools at 36.3 per cent in 1962-1963 and later at 11 per cent in 1972-1973.

In higher institutions of learning, Tutsi students were 8.5 per cent at the National University of Rwanda (NUR), 6 per cent at NPI and 3 per cent in foreign schools. Fictitious figures were published during the period of persecution.

According to these figures, Tutsi students were between 50 per cent and 70 per cent. These were mere fantasies which did not correspond to reality. Lying was one of the weapons used by the Kayibanda regime and its allies.

The real causes of the 1972-1973 events originated from within Kayibanda’s regime itself. He provoked these events with the view of reconstituting the unity PARMEHUTU. The Tutsi, who were portrayed as the real enemies of the Hutu, became a scapegoat.

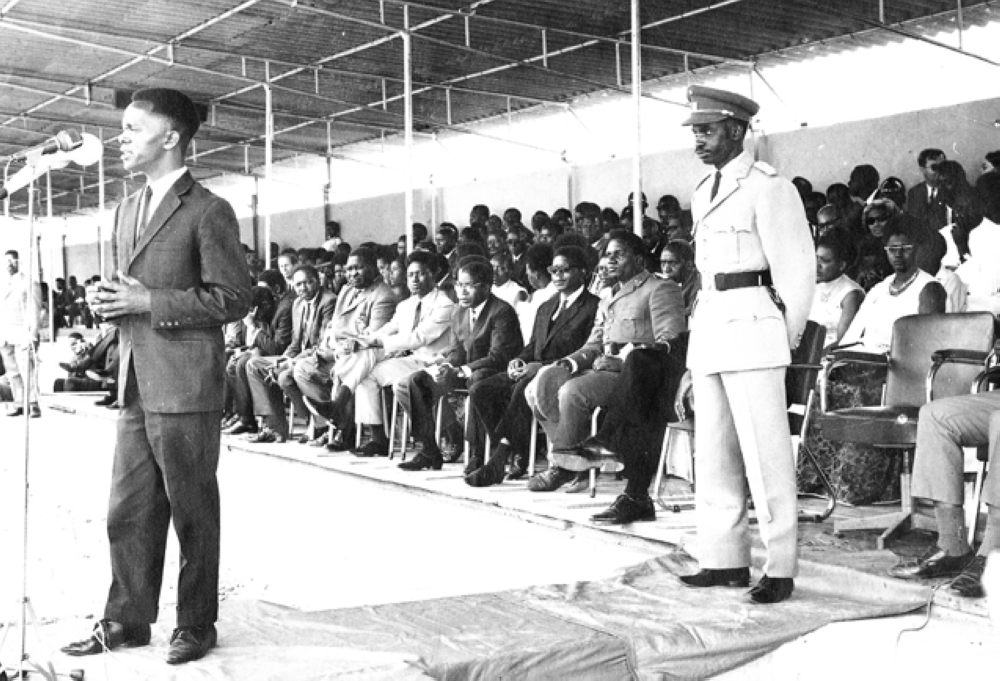

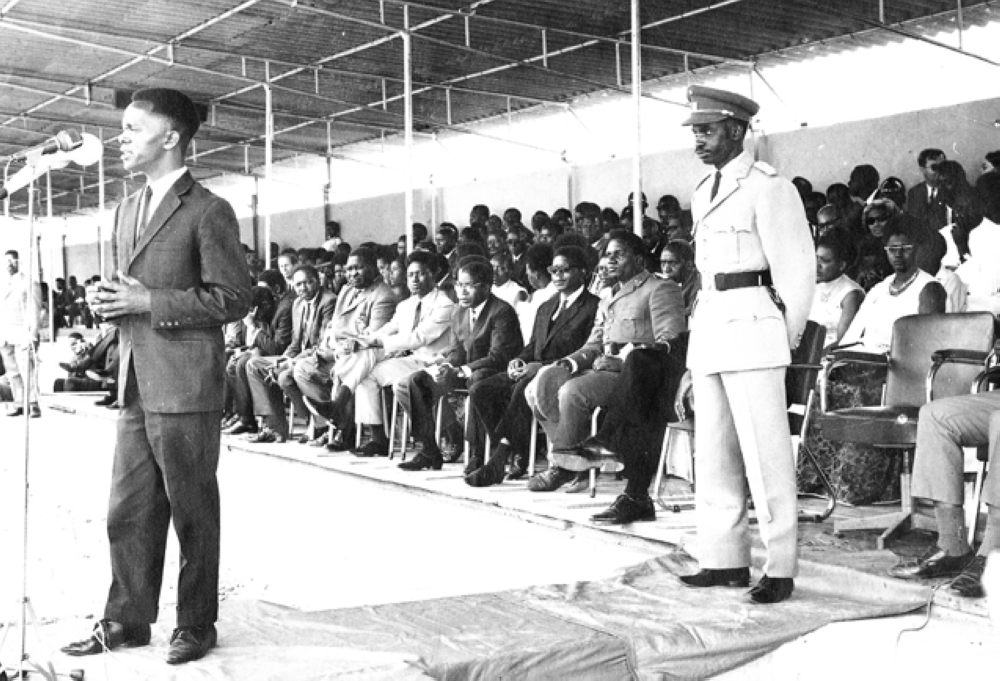

The coup of July 1973 The 1972-1973 events led to the coup d’etat, which was executed by Minister of Defence Juvenal Habyarimana. The northern group that Habyarimana represented was very influential in the army and did not want Kayibanda’s friends to carry out operations of persecuting Tutsi. However, this was just on the surface.

It was obvious the military command was aware of everything and involved in the campaign. It could not have taken place without their blessing. The military took control of the operations the very moment it wanted to control the country.

However, no study specifies the role played by the army in these events. By the end of February 1973, President Kayibanda had lost his control of power. He was a victim of sectarianism and divisions within his own party.

The fact that he was witch-hunting the Tutsi did not help him to survive. Before the end of his presidential term in May 1973, President Kayibanda and his confidants did not want to leave power. They yet provoked a political crisis when they amended the constitution to the discontent of their opponents, as did other politicians and the military.

The presidential term was changed from 4 to 5 years with unlimited eligibility. The First Republic was already exhausted by many years of infighting when the coup d’état of July 5, 1973 occurred. PARMEHUTU was completely tired and exhausted.

Word has it that it was not overthrown but “rather picked like a rotten fruit.”.

Politics

Years of infighting in PARMEHUTU led to 1973 coup d’état

In the previous article in this series, we realized how power was concentrated in the hands of a small clique from Gitararma and this progressively reduced the geographical base...