The purge saga in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) continues. The latest names of senior military officials, who reportedly have been removed from their posts, as tweeted by Jennifer Zeng, a writer, reporter and China expert, are: Wang Haijiang, Commander of the Western Theatre Command; Wang Peng, Minister of the Training and Administration Department of the Central Military Commission (CMC); Wang Zhongcai, Commander of the Eastern Theatre Command Navy; and Ding Laifu, Commander of the 73rd Group Army. Defence Minister Dong Jun is also under investigation.

All these were one-time favourites of President Xi Jinping. December 2024 Purge China’s Ministry of Defence announced in December 2024 that Admiral Miao Hua, a very senior figure within the PLA, had been suspended and is under investigation for ‘serious violation of discipline’. Admiral Miao Hua, the number four military leader below Xi, oversaw the political and organisational work of the PLA.

Miao’s ouster makes him the third PLA general in charge of political and organisational work Xi has purged and the second of the six members of the 20th CMC. Admiral Miao Hua’s military career took off soon after Xi came to power. In 2014, he received a major promotion to become the political commissar of the PLA Navy, making an unusual switch from a career in the Ground Force.

Three years later, he was promoted into the CMC, the apex of military power. As the chief political commissar of the PLA, Miao was tasked with ensuring the PLA’s loyalty to the ruling Communist Party. He oversaw promotions in the military, vetting key candidates for their political loyalty.

Xi might have viewed Miao as becoming too powerful and independent and wanted to uproot what he saw as a bastion of influence that he could not fully control. Miao’s downfall comes less than a year after former defence minister Li Shangfu was removed from the CMC. By suspending Miao, Xi has further demonstrated a willingness to remove a perceived loyalist at the highest levels of China’s military to ensure compliance with his political agenda and set an example.

Xi wants to ensure the PLA develops in the direction he intends. An official announcement in late December also confirmed the removal of two former PLA Generals from the National People’s Congress (NPC), You Haitao, former deputy commander of the PLA Ground Force, and Li Pengcheng, former commissar of the PLA’s Southern Theatre Command Navy. Another case is of He Weidong, who has long been a key member of Xi Jinping’s core military circle, having served as the commander of the Eastern Theatre Command and was directly responsible for Taiwan Strait affairs.

He is currently the No. 3 figure in the PLA. His influence within the Party and military was immense.

More recently he has been CMC’s vice chairman. He Weidong’s houses were searched, and he was taken away on the spot after returning to the building following the end of the “Two Sessions” of interrogation on March 11. Next, Zhao Keshi, a General born in 1947, once served as the Commander of the Nanjing Military Region and the Minister of the General Logistics Department, and was well-versed in military funding flows, material allocation, and the military-industrial system.

His downfall signifies the unravelling of a corruption chain. Is it related to a major anti-corruption purge in the military? Or has factional struggle within the military entered a new phase? The focus of Xi’s purge has shifted ominously from financial corruption to political reliability. More than half of the CCP’s CMC members have either been removed or have encountered significant problems.

Several Fujian-origin army commanders have been detained, indicating a fierce escalation of factional struggles. Fujian has long been an important base for Xi Jinping. The CCP is trying to cover up information regarding Qin Gang and Li Shangfu’s cases to minimise the impact on Xi Jinping’s reputation.

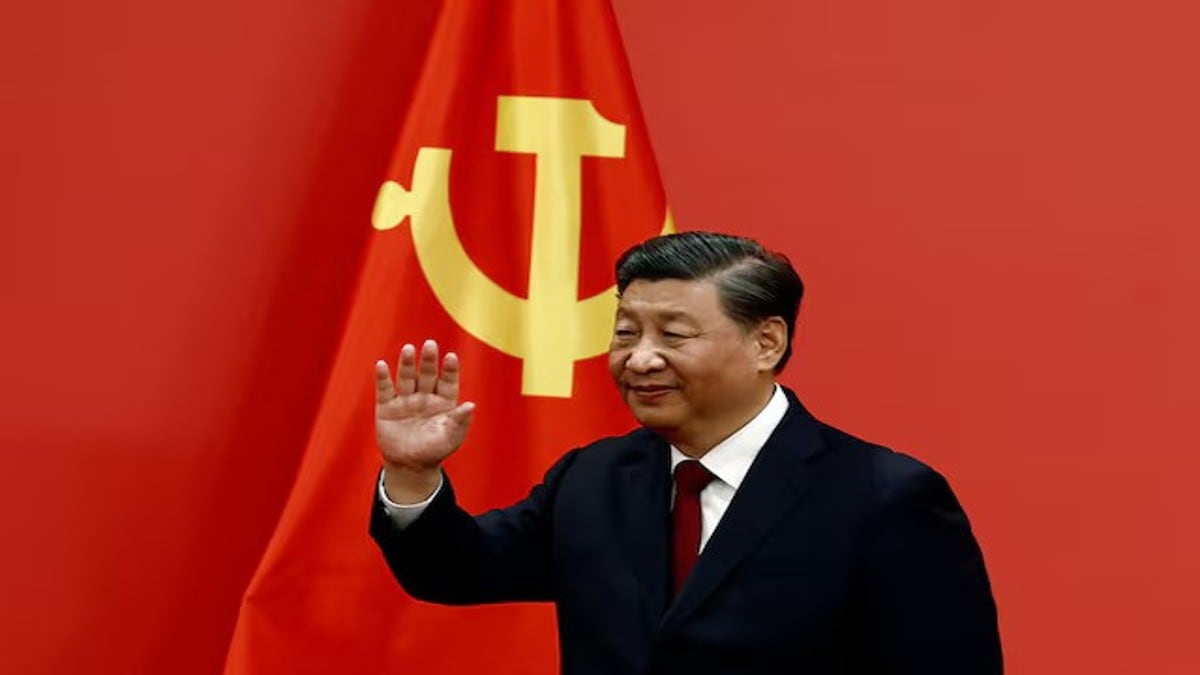

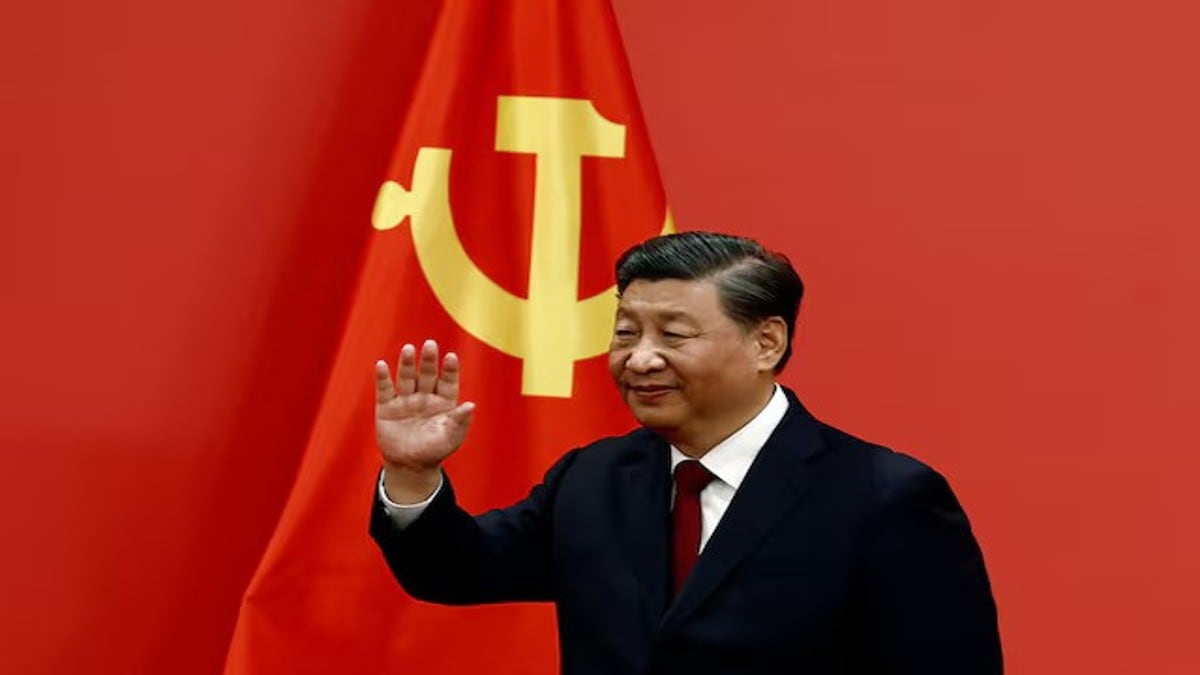

It is believed that the downfall of these people signifies that Xi Jinping’s power base in the military has been fundamentally shaken. Would Xi Jinping be stepping down at or before the Fourth Plenary Session of the CCP? Xi’s Unrelenting Campaign Anti-corruption efforts have been on the agenda of successive Chinese leaders, though the effectiveness of these campaigns has been diverse. Since economic reforms began in 1978, political corruption in China has grown significantly.

The types of offences vary, though usually they involve trading bribes for political favours, such as trying to secure large government contracts, or subordinates seeking promotions for higher office. Upon taking office in 2013, Xi vowed to crack down on “Tigers and Flies”, that is, high-level officials and local civil servants alike. He also tried to convince his colleagues on the Politburo that corruption would doom the party and state.

Several provinces faced the brunt of his anti-corruption campaign, Guangdong, Shanxi, Sichuan, and Jiangsu, in particular. In addition to curbing corruption, the campaign was also meant to reduce regional factionalism and dissolve entrenched patron-client networks that have flourished since the beginning of economic reforms in the 1980s. The Central State-owned enterprises (SOEs) were also investigated.

Between 2013 and 2017, twelve top executives of core central SOEs were removed from office due to corruption charges. Most of the officials investigated and removed from office had faced accusations of bribery and abuse of power. The campaign caught over 120 high-ranking officials, including about a dozen high-ranking military officers, several senior executives of SOEs, and five national leaders.

As of the end of 2023, approximately 2.3 million government officials had reportedly been prosecuted. In January 2025, President Xi emphasised that corruption remains the “biggest threat” to the Communist Party, underscoring the government’s commitment to addressing entrenched corruption.

Xi, who also directed the anti-graft efforts of the military through his holding the office of Chairman of the CMC. Proposed National Supervisory Commission The proposed constitutional changes published in February 2025 envisioned the creation of a new anti-graft state agency that merges the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and various anti-corruption government departments. The proposed National Supervisory Commission will be the highest supervisory body in the country and will be a cabinet-level organisation outranking courts and the office of the prosecutor.

Deep Rot at Highest Levels of PLA Command? Heads rolling at the highest levels of PLA command expose deep rot and large-scale corruption that have been exposed in the last nearly a decade. The PLA now faces a significant leadership crisis. Military commanders are known to be notorious for selling promotions, taking bribes and running side businesses that are hollowing out the PLA from within.

Xi was forced to launch a second wave of purging in 2023. The sacking of the heads of the PLA Rocket Force, officials from the Equipment Development Department, and more recently, Adm Miao from Xi’s inner circle at the CMC, has sent shock waves. Miao was responsible for ensuring political loyalty throughout the officer corps.

His removal suggests even Xi’s handpicked enforcers can’t also be trusted. Blind loyalty to the CCP has had a higher premium than military competence. As Xi’s geopolitical ambitions grow, he finds himself commanding a military rife with uncertainty, distrust and corruption.

The high turnover in leadership is also very bad for the PLA’s effectiveness and strategic continuity. Mid-level officers are already imagining that they could be next on the block. Officers are preferring to play it safe and take no risks.

The PLA may project strength through military parades and new equipment, but its leadership core is deeply compromised. Corruption’s Direct Effect on Operational Preparedness When internal reports show that corruption has directly compromised China’s strategic weapons, it is a new low. Funds meant for the PLA Rocket Force were allegedly misappropriated.

Affecting silo construction quality and questionable missile components, including fuel. Xi’s anti-corruption campaign exposes how unprepared his forces might be for actual conflict and weakens his resolve to push for a Taiwan takeover. Also, his capability to secure the South China Sea and handle border disputes with India, or intimidate any of its neighbours through military posturing.

It also threatens his grand vision of Chinese military dominance by 2049. It emboldens the US and makes Eastern neighbours feel secure. Yet, this instability also creates dangerous uncertainty.

The crackdowns on graft inside the PLA are motivated at least in part by a desire to increase military readiness after viewing the effects of corruption on the Russian armed forces during the invasion of Ukraine. Reactions to the Campaign Xi Jinping inherited a political party that was faced with pervasive corruption and in danger of collapse. Xi Jinping obviously believes that his anti-corruption campaign was vital to enable him to save the Party.

The campaign is believed to enjoy popular support among most ordinary Chinese. The anti-corruption campaign’s Chinese public approval rating was 71.5 per cent.

Some analysts felt that Xi’s anti-corruption campaign looked more like a Stalinist political purge where he relied on the regulations of the party and not on the laws of the state; the people carrying it out operated like the KGB. Factional struggle has been suggested as another explanation. Effectively Xi cleared up what once used to be “patron-client” relationships, rather than merit, which became the primary factor in securing promotions, giving rise to the formation of internal factions based on personal loyalty.

Proponents of Xi’s view believe that the ultimate aim of the campaign is to strengthen the role of institutions, thereby creating a more united and meritocratic organisation and improving efficiency for governance. Xi’s campaign did curb corrupt practices at all levels of government. It may have restored public confidence in the CCP’s mandate to rule and also returned massive ill-gotten wealth back into state coffers, which could be redirected towards economic development.

Need To Address Systemic Issues Many contend that the root of problems will not be permanently fixed until much deeper systemic problems are addressed, including the judicial system. Many regulations and laws governing cadre work and public service were rarely enforced. There were two prevailing approaches among the officialdom.

Firstly, “If everyone else is doing it, then it must be okay,” and secondly, “I probably won’t ever be caught anyway.” Bribe giving and accepting is common and considered a normal process in Chinese society. This needs to be looked down upon and changed.

To Summarise A renewed anti-corruption drive has led to the dismissal of a remarkable number of defence ministers and Chinese top brass. Xi’s purge of the PLA is widening. There are unconfirmed reports that the current defence minister, Dong Jun, is under investigation for corruption.

The sacking of Admiral Miao Hua is a clear sign that graft and disloyalty within the military continue to haunt China’s leadership. Not even Xi-appointed officers are safe from the ongoing purge. In front of the entire military top brass, Xi referred to political war as the “lifeline” of the PLA, emphasised the need for party leadership to be upheld, and demanded that senior officers “introspect, engage in soul-searching reflections, and make earnest rectifications”.

In the early years of Xi Jinping’s war on corruption, he consolidated control over the world’s largest military by taking down powerful generals from rival factions and replacing them with allies and protégés loyal to himself. A decade later, he is still engrossed in a seemingly endless struggle against graft and disloyalty. China has purged nine generals from its national legislative body, a move that analysts say exposes corruption in the senior army ranks and could slow Xi’s campaign to modernise the military and raises questions about China’s ability to fight a war.

Xi had remained unsure of the PLA’s leadership and their commitment to the party and its goals. Over a dozen top generals have been removed from their posts or placed under investigation since mid-2023, including two consecutive ministers of defence, Li Shangfu and his predecessor, Wei Fenghe. Xi has also fired the two generals who headed the PLA Rocket Force, which is in charge of China’s missile and nuclear capabilities.

If the investigation into Dong Jun is confirmed, this would turn him into the third consecutive defence minister to be fired for corruption. Has Xi misjudged his personal appointments? As the party is pushing for an ever-greater focus on conflict preparedness. Xi has called for China’s top national security officials to be prepared for “worst-case and extreme scenarios” and has repeatedly exhorted the PLA to be ready for war.

But the corruption may dampen Xi’s appetite for conflict in the short term. His pursuing the purge is with geopolitical goals in mind. Tackling any signs of disloyalty in the military has moved to the top of Xi’s to-do list.

Xi has stated that the PLA should be able to ‘fight and win wars’. Given China’s geopolitical situation and designs on Taiwan, this means a military which can confidently prevail over the United States in a regional conflict. While in terms of material capabilities, there are signs of success.

China’s current military production capacity is among the best, and some of its weapon systems are world beaters. PLA is also focused on ‘informatised’ and ‘intelligentised’ warfare backed by integrating AI and the cyber domain and multi-domain cognitive control across conventional air, land and sea combat. However, material capability is of little use if not backed by an effective command structure.

The Strategic Support Force (SSF) that focused on information dominance was dissolved to create three new branches that all sit directly under CMC control. This move indicates a desire for direct political supervision of China’s integrated strategy at the highest level. The intent of building the advertised silos was always unclear.

The construction would be so flawed and missiles would be compromised was unexpected. It will take some time for China to clean up the mess and restore confidence in the Rocket Force’s competence and trustworthiness. In 1938, Mao said, “Every communist must grasp the truth; political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.

” In modern China, it implies that the authority of the supreme leader rests upon his control over the military. Xi’s urgent mission now is to fill the top ranks of the PLA with officers whom he trusts to “fight and win wars”. Because of corruption and purges, the military morale and cohesion are being hit.

International credibility is also getting eroded. The PLA’s capabilities might be less formidable than officially announced. This is capped by the perception that the PLA’s lack of overall combat experience and very few multi-nation exercises place it at a disadvantage.

To offset perceptions of PLA incompetence, Xi has chosen demonstrations of capability through increased large-scale exercises around Taiwan. If Xi cannot trust the PLA’s leadership or capability, he is less likely to risk combat operations against Taiwan or India. The importance of success in such conflicts is too high for Xi’s own legitimacy.

The writer is former Director General, Centre for Air Power Studies. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.

.

Politics

Xi’s sacking of Chinese Generals continues: Is the PLA corrupt or is he insecure?

If Xi Jinping cannot trust the Chinese military leadership or capability, he is less likely to risk combat operations against Taiwan or India. The importance of success in such conflicts is too high for the Chinese president’s own legitimacy