Jim Chalmers will end up counting the cost of his tough talk about interest rates after a week of avoidable argument about who bears the blame for household pain. There is no sign the treasurer has helped the government or himself with his statement that higher rates were “smashing” the economy, which set off the argument about whether he was blaming the Reserve Bank for the problem. In fact, there are good reasons for thinking it has backfired.

First, Chalmers has lost ground personally. The Resolve Political Monitor tracks the personal ratings of most federal leaders and has generally found the treasurer has a positive or neutral rating. That changed last week when his net rating went negative.

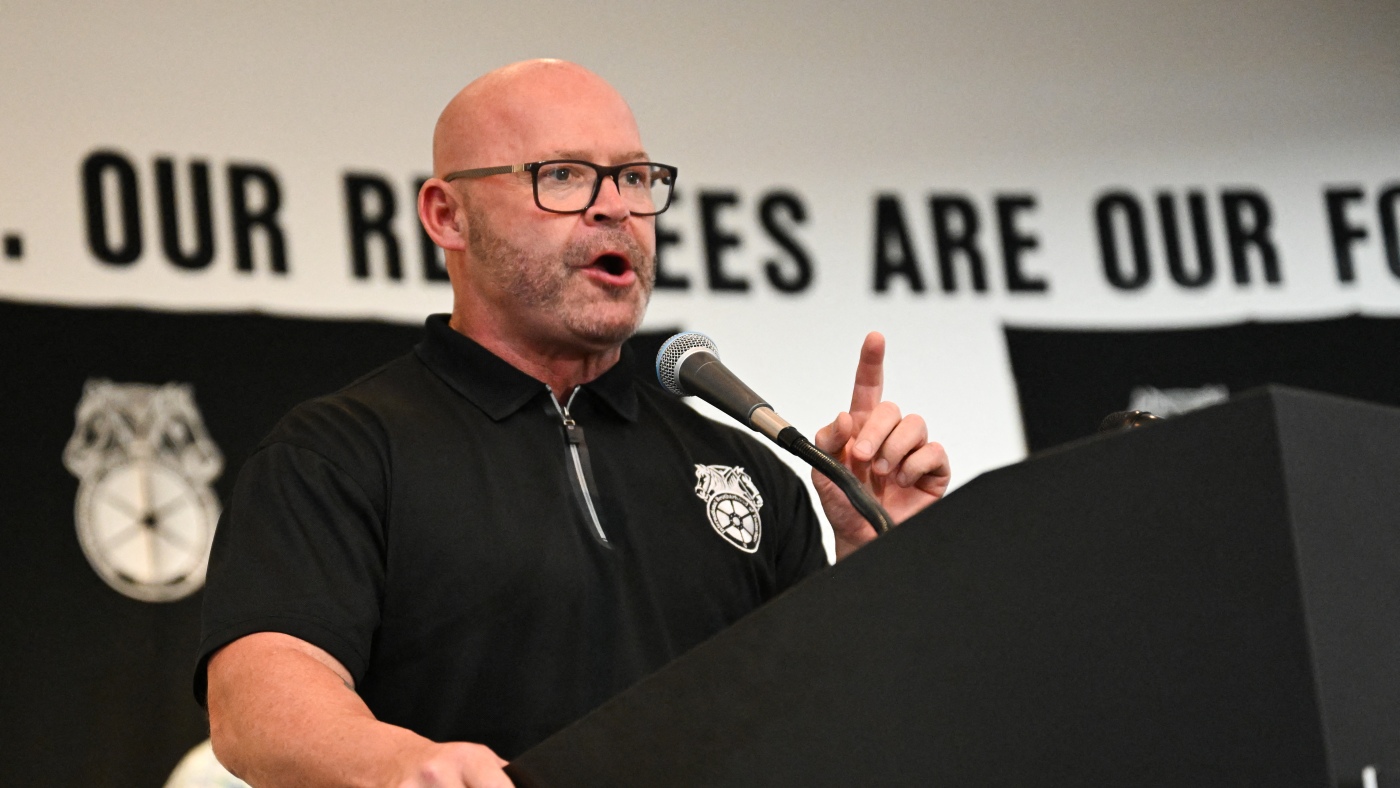

The latest survey found that 18 per cent had a positive view of him, while 21 per cent had a negative view, which meant a net negative rating of minus three per cent. Treasurer Jim Chalmers Credit: AAP This is only one small fact in the regular polling of the government’s performance, and it is important to note that most voters are yet to make up their minds about Chalmers. The survey found that 33 per cent were not familiar with him and 29 per cent were neutral about him.

In net terms, however, he did not benefit from his decision last week to use the sharper language about interest rates. Second, the government is not making any headway in this fundamental argument about who is responsible for rising prices. Chalmers did not blame the Reserve Bank for inflation, of course, but his remark set off a week of argument about where the blame lies.

And the government is losing that argument. When the Resolve Political Monitor asked voters about inflation last June, it found that 44 per cent believed the government had the greater responsibility for keeping inflation down. This fell to 42 per cent on the same question in July.

But it just rose to a narrow majority. The latest survey found that 51 per cent believe the government has the greater responsibility. It is fair to say that “responsibility” is different from “blame” but the message is that Labor owns this problem.

Pointing to Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock, or even attempting a quiet nod of the head and a glance in her direction, will not change that. “Chalmers is now rated in negative territory for the first time,” says Resolve director Jim Reed. “That is likely a result of both a general decline in Labor’s standing and also his rhetoric becoming less positive.

He’s been a pretty strong communicator, but tone is important in forming opinions.” This is a danger sign for Chalmers when he has been so effective in attack and defence for so long. He mocked Peter Dutton three weeks ago for leaving the shards of his glass jaw on the floor of parliament – a light touch that hit home.

Then he felt the need to go big, and hard, with his claim that the Opposition Leader was the most divisive leader in modern Australian history. He forgot that when you are trying to tear down an opponent, ridicule works better than rage. Labor feels it has the facts on its side.

It is true that the Reserve Bank’s interest rate decisions have cut growth. It is also true the economy would be weaker if government spending did not shore up growth. But those two facts simply highlight the way monetary and fiscal policy are working against each other.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Treasurer Jim Chalmers during Question Time. Credit: The Sydney Morning Herald Wayne Swan was no help to Labor by leaping into the argument and accusing the Reserve Bank of “punching itself in the face” – leading to suspicions that Chalmers wanted the former Labor treasurer, his former boss and mentor, to come to his defence. The treasurer is stuck in the slow lane of the national economic argument right now – and it shows.

He can talk about big decisions, such as energy subsidies and personal tax cuts, and he can point to progress on ideas like competition reform. But he cannot hit the accelerator just yet and swerve into the policy fast lane too soon. Chalmers has to wait for the mid-year budget update in December to outline his next plans on fiscal policy and he has to wait for the election campaign next year to reveal his fix for households on the cost of living.

Australians will only get a true measure of the treasurer when he puts his foot to the floor. Right now, he is in the uneasy position of assuring voters he has the answers without giving them anything too solid. His news on Sunday, for instance, was the estimate that tax revenue would be $4.

5 billion lower from the fall in commodity prices – a classic example of empty news because it is not about an actual policy decision, it is largely theoretical and the forecasts are always wrong anyway. No wonder the economic debate is consumed with a blame game instead. The row over interest rates has been a gift to Peter Dutton and Angus Taylor because they have so little to offer on the economy.

The Opposition Leader and shadow treasurer are yet to outline any significant policy on the cost of living. Taylor’s vague “back to basics” theory on government spending is about as detailed as they get. The Coalition is clearly heading toward a policy that scales back spending, but it skirts questions about what this means for millions of voters.

Chalmers remains one of the government’s best performers, and the headlines about last week’s blame game will fade fast. The real test for the treasurer is in choosing what to fight for in the election campaign to come. Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis from Jacqueline Maley.

Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter here ..