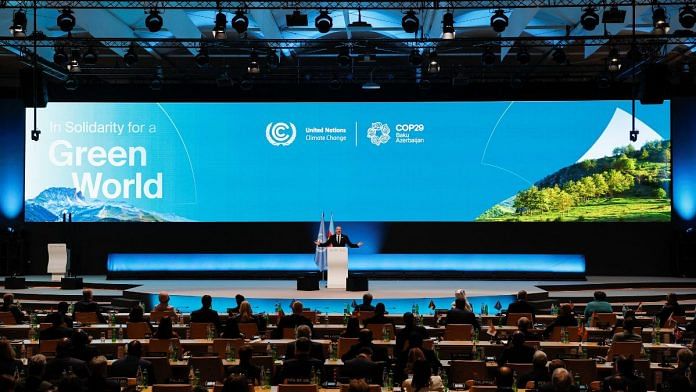

Bengaluru: All United Nations member countries will soon be able to trade carbon credits under supervision on a global carbon market. This was made possible after Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement was adopted on the first day of the climate change summit COP29 at Baku, Azerbaijan.

Multiple attempts previously to both define and adopt it have failed. Yalchin Rafiyev, the lead negotiator of COP29 from Azerbaijan, after Monday’s adoption of the article, called it a “game-changing tool”. Once operationalised, the UN carbon market would allow the world to save $250 billion a year while implementing climate plans, he said.

However, many experts are still sceptical about not just the article, but also the entire idea of carbon markets and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement. ThePrint explains Article 6 and its subsections, what the carbon credits markets will do, and what climate experts think of them. Also Read: Global carbon market ‘breakthrough’ can save $250 bn annually, says COP29 lead negotiator Rafiyev Article 6 or A6 of the Paris Agreement deals with rules that enable various countries and global entities to use carbon markets and credits to jointly work towards achieving net zero.

Essentially, countries or entities with higher carbon emissions can theoretically make up for what they emit by investing or paying for an environmental activity somewhere else so that they can still achieve their climate targets. This is why carbon credits are also called carbon offsets. However, given its ill-defined language and lack of enforceable guidelines, the article has already caused much confusion, led to misinterpretations, and allowed for the exploitation of its mechanisms.

Putting A6 at the forefront and setting out substantive guidelines for it was a priority for this conference, according to the COP presidency. It outlined two markets and one non-market mechanism to implement this. Subsection 6.

2 allows countries to trade carbon credits, known as internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs), to meet their NDCs under the Paris Agreement. Article 6.8 lays out the framework of non-market methods for climate cooperation between countries, where instead of trading carbon credits or emissions, countries share knowledge, technology, financial aid, and increased emissions tax, among others.

On Monday, members adopted subsection 6.4 which enables the formation of a new global carbon market overseen by a United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)—the Article 6.4 Supervisory Body—from 2025.

This will allow countries and companies to trade Article 6.4 Emission Reduction Credits (A6.4ER credits) authorised by the UNFCCC guidelines that are yet to be established.

Countries use carbon credits to offset emissions in a way that they can achieve their targets under the NDCs. However, NDCs have come under criticism themselves. NDCs are plans laid out by various countries that are unique to their ability and interest in contributing to mitigating climate change.

They draw from the overarching goal of the historic Paris Agreement, adopted at COP21 in 2015, where the 196 participating UN members agreed to limit global warming below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This is a legally binding agreement that is revised and updated every five years.

Under their NDCs, many countries have pledged net zero. For instance, India announced its target to reach net zero by 2070 at COP26 in 2021. These pledges have driven investment in global climate efforts at varying levels and degrees globally, including creating jobs in clean energy.

However, while having an NDC is legally binding, achieving it is not. Moreover, many expert individuals and institutions have said that the NDCs are not ambitious enough to meet the scale of change required. A report from the World Resources Institute, said, “Far from limiting global temperature rise to 1.

5°C, the actions outlined in existing NDCs are on track for a catastrophic 2.5-2.9°C of warming by 2100.

” Carbon offsets have also come under tremendous criticism for being a tool to distract from actually increasing emissions. There are three main criticisms of carbon offsetting. Firstly, experts say, compensating for emissions by reducing emissions elsewhere does not result in a real reduction in emissions, especially considering that the build-up of atmospheric greenhouse gases is cumulative.

Secondly, studies have shown that carbon accounting—that is, the way countries and entities measure their emissions and the offsets they require—can be unreliable or, even false. This leads to “phantom credits” where the emissions and their offset don’t actually match. In some cases, carbon offset projects can also fail.

Researchers said increasing emissions also render carbon offsetting useless. They describe it as “overconfidence in climate overshoot”. Lastly, many describe the concept of carbon credit markets as greenwashing, where countries and entities give the impression of carbon neutrality while continuing to pollute.

A UN Trade and Development report has said that while the least wealthy nations emit less than 4 percent of global emissions, they face the full brunt of climate change. Therefore, it said, carbon markets must link economic growth with climate action. Last year, negotiations on A6 failed because the European Union insisted on more transparency and clearer guidelines, while the US opposed the demands.

The biggest point of contention was the definition of what constitutes a good carbon credit. At the Bonn intersessional climate conference in June, the EU and the US reached an agreement on Article 6.2 and, later, Article 6.

4. However, negotiations are still ongoing, and actors will continue to voice concerns, frame and reframe guidelines, and improve standards. Subsequently, the supervisory body will develop credit rules that can be implemented from some point in 2025.

Some experts at the event have raised concerns about the risk of pushing A6.4 through so quickly without fleshing it out fully. They say it sets a poor precedent and, more importantly, lacks any requirement to monitor how functional the credit projects are.

“Kicking off COP29 with a back-door deal on Art 6.4 Supervisory Body recommendations sets a poor precedent for transparency and proper governance. Adopting these rules on highly sensitive and contentious issues during the plenary on day 1 reduces crucial time for countries and observers to look at and debate the issues, undermining trust in UNFCCC decision-making processes,” Isa Mulder, global carbon markets expert at Carbon Market Watch, said in a statement.

Other concerns have also followed about the lack of a proper plan for evaluating the impact of carbon credits. In a press statement, Dhruba Purkayastha, Director of Growth & Institutional Advancement at Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), said, “Overall, this is a constructive step towards the operationalisation of Article 6.4.

However, some additional steps are necessary for rigorous implementation.” Outlining a few, he added that it is important to ensure that less than best approaches are viable, the risk assessments of carbon reversal technology needs to be evaluated, and a minimum period of monitoring post crediting to assess the impact of the credit. (Edited by Sanya Mathur) Also Read: COP 29, Day 1: Baku summit sets tone with ambitious finance goal amid leader absences, Trump threat var ytflag = 0;var myListener = function() {document.

removeEventListener('mousemove', myListener, false);lazyloadmyframes();};document.addEventListener('mousemove', myListener, false);window.addEventListener('scroll', function() {if (ytflag == 0) {lazyloadmyframes();ytflag = 1;}});function lazyloadmyframes() {var ytv = document.

getElementsByClassName("klazyiframe");for (var i = 0; i < ytv.length; i++) {ytv[i].src = ytv[i].

getAttribute('data-src');}} Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. Δ document.getElementById( "ak_js_1" ).

setAttribute( "value", ( new Date() ).getTime() );.