The latest exhibition at Poolside Gallery started out as a bit of a lark. Read this article for free: Already have an account? To continue reading, please subscribe: * To continue reading, please subscribe: *$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.

00 a X percent off the regular rate. The latest exhibition at Poolside Gallery started out as a bit of a lark. Read unlimited articles for free today: Already have an account? The latest exhibition at Poolside Gallery started out as a bit of a lark.

“I was making a joke to a friend months ago, I was like, ‘What if I brought the club to the gallery?’” says artist Mahlet Cuff, whose two-person exhibit with Evan Tremblay, , opened last week. is a playful show, with its throbbing score of classic house music and kaleidoscoping scenes of dance and nature enveloping the gallery. It’s tons of fun to step into.

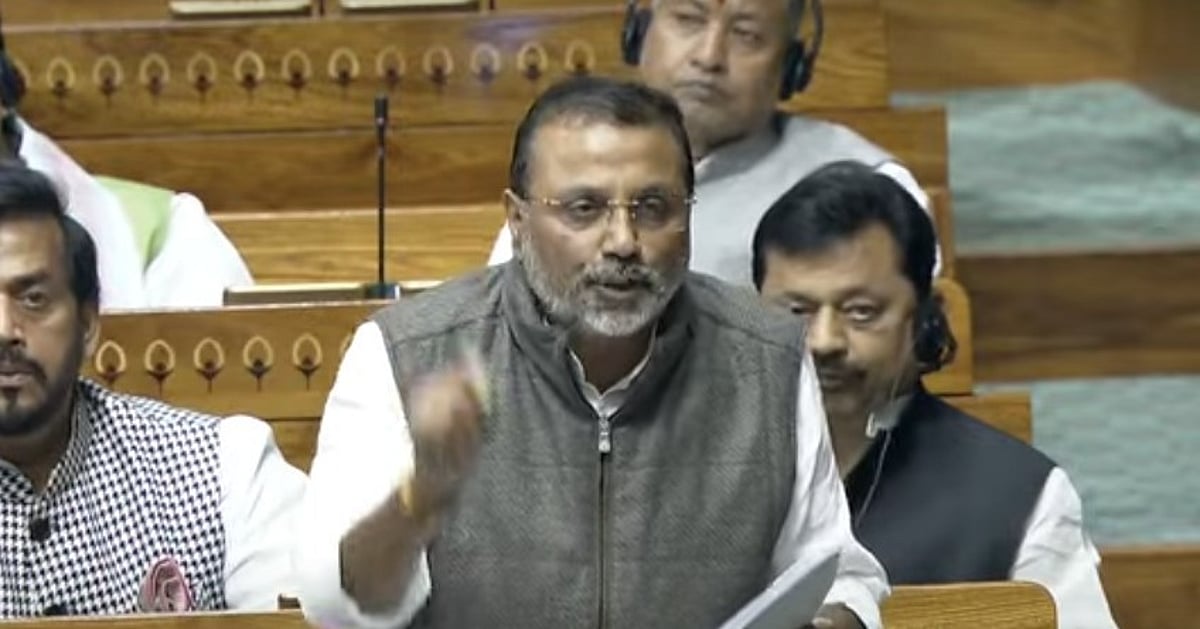

photos by MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS Video Pool’s artists-in-residence Mahlet Cuff (left) and Evan Tremblay. The pair’s two-person exhibit, World Building as Radical Imagination, opened last week. But it also plays with serious questions about technology, community and freedom — plays, because the artists have the finesse to evoke rather than bludgeon with these themes.

Born from the Video Pool and TakeHome Art House Media Arts + Technology Residency, is most directly about two things: utopia and dance. Is utopia actually possible in our lifetime? Cuff, 26, and Tremblay, 37, dare to say yes in an exhibit rich with sights and sounds that bring to mind activist Emma Goldman’s quip, “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution.” Their best case for dance’s utopian elements is the sheer wit and pleasure of the exhibit itself, which sweeps you up in ways that few shows with this many internal citations can.

But they say yes in different ways, as is really two works and two visions in dialogue. On one panel, Cuff’s piece, , channels Detroit techno, Chicago house and ballroom culture with samples of intersectionalist and Afrofuturist-adjacent thinkers. Tremblay’s work, , on the other panel, draws on different influences, from psychedelia to his Métis heritage.

“I come from a ‘psy-trance’ background, and my interest is specifically festival culture and rituals of rebirth and creation,” he says. Psy-trance, a partial throwback to ’60s counterculture, pairs pulsing, electronic beats with cosmic vibes. It thrives in open-air festivals such as Shambhala in British Columbia or Shankra in the Swiss Alps — part rave, part spiritual retreat.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS The works by Mahlet Cuff (left) and Evan Tremblay interact with each other. Tremblay’s background is in landscape architecture and environmental design, skills he puts to impressive use in designing projections and installations for music festivals, as well as for . He now lives south of Riding Mountain, but spends a lot of time collecting materials in Duck Mountain, drawn by the region’s roots in traditional harvesting.

His part of the exhibit features a “living altar” made up of materials, including deer bones and lichen, tied to traditional Métis culture and harvesting. It also features swirling projections of the landscape melting into each other through feedback loops he likens to the Earth’s natural rhythms and cycles. “My practice envisions a world where human relationships with the land and technology evolve in ways that are symbiotic, regenerative and deeply rooted in reciprocal exchange,” he says.

Staring into these kaleidoscopic forms, it’s hard not to ask: what does Tremblay make of the ’60s counterculture and the way so many of its grand ideals slipped into stoned escapism? “It takes time, it takes time. A big inspiration for my work is one of the few remaining hippie communes from the ‘70s that actually did devote itself to spirituality,” he says. Tremblay also cites the influence of sci-fi titan Isaac Asimov, whose mostly optimistic visions of the future put science and reason at the centre of things.

For all his fondness for a certain back-to-the-land utopianism, Tremblay isn’t anti-tech. The whole exhibit pulses with his know-how and gadgetry. Cuff (who uses they/them pronouns) is inspired by other influences and their piece responds differently to similar questions.

A favourite DJ of Winnipeg’s underground dance scene, Cuff curates the exhibit’s soundtrack. Their panel is a trippy remix of archival footage from ‘80s and ‘90s underground Chicago dance scene, where house music was born. MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS World Building as Radical Imagination features music and projections.

But Cuff’s inspiration also hearkens back to an earlier moment in urban dance culture. “Detroit is definitely an influence on this show. I’m thinking not only about house music, but dance music overall,” says the artist.

“And recognizing that this is Black music, something that’s oftentimes erased.” Detroit in the late ‘70s and ‘80s was the cradle of techno, a genre of modern dance music pioneered by three Black DJs — Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson — known as the Belleville Three. In just a few decades, Detroit had gone from the poster child of the American Dream — a symbol of industrial power and innovation — to a stark symbol of its collapse, as automation, outsourcing and economic decline hollowed out the city.

Early techno echoed this collapse but also pushed defiantly forward. Using synthesizers, drum machines and sequencers, the Belleville Three crafted a robotic, hypnotic sound inspired by the rhythms of Detroit’s factories — but infused it with the soul and futurism of Black music traditions. Atkins, widely regarded as the Godfather of Techno, found his muses in Kraftwerk, Parliament-Funkadelic, Prince and science-fiction writers such as Asimov — a mix that would later be seen as helping set the Afrofuturist movement in motion.

“This wasn’t escapism, and I don’t want people to escape. I want people to face the realities that are currently happening. I think escapism is another form of white supremacy,” Cuff says.

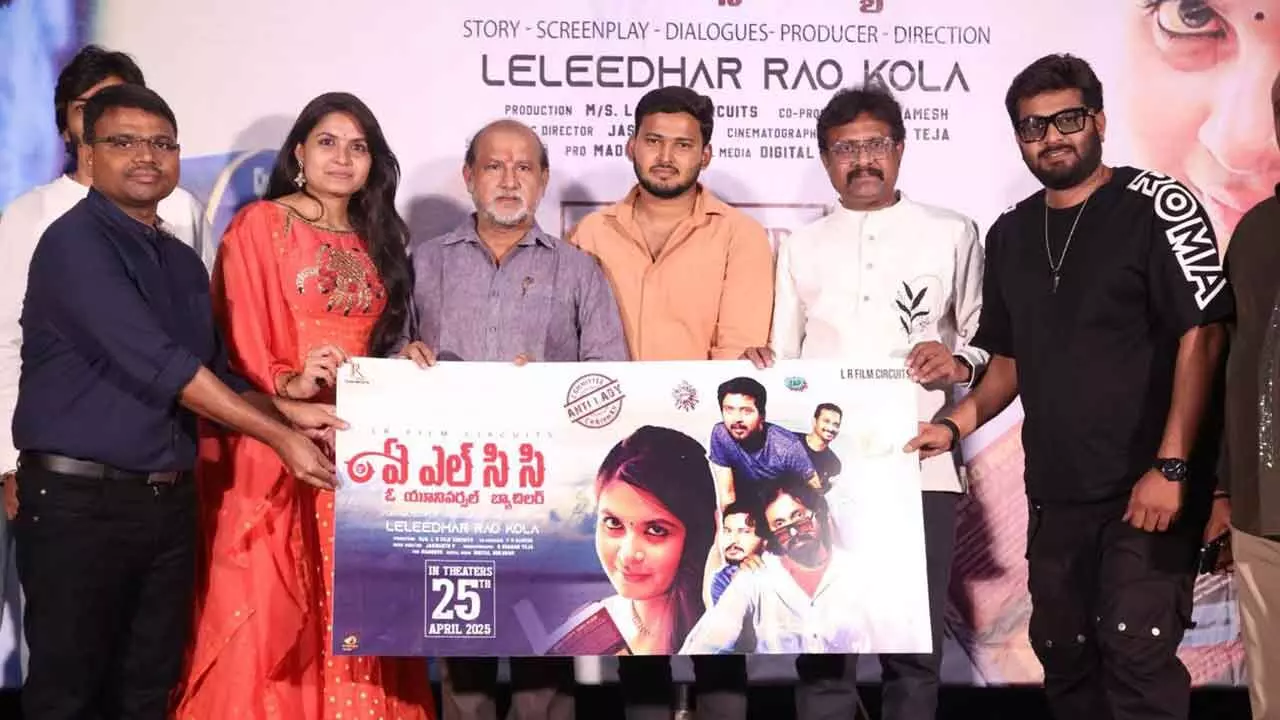

Detroit’s techno scene offered not just refuge, but a vision of the future, one restoring Black communities’ agency over both city politics and even technological progress itself. Cuff leverages this Afrofuturist theme by incorporating recordings of iconic sci-fi writer Octavia Butler, as well as other Black authors, into . MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS World Building as Radical Imagination includes a score of classic house music and kaleidoscoping scenes of dance and nature.

The soundtrack and visuals pay homage to pioneering DJs such as Frankie Knuckles and the early Chicago house scene. That scene emerged a few years after Detroit and soon spread throughout the Midwest as a vital cultural space for queer Black and Latino communities. During Elections Get campaign news, insight, analysis and commentary delivered to your inbox during Canada's 2025 election.

“Dance music is inherently political because the reasons people come into certain spaces to be together is always political,” Cuff says. Despite their strongly contrasting visions, Cuff and Tremblay have designed their works to not only to share space, but also interact with one another. “Where (the feedback) is picking up both Mahlet’s videos and mine is the same loop, but is reacting differently to each of them.

They’re both kind of part of the same pool of utopian futures of exchange,” says Tremblay. “Everyone has the ability to create their own utopia,” adds Cuff. “But I think asking two people to be in a space to think about radical imagination would be completely different if it were individual exhibitions.

The fact that we’re in collaboration says a lot.” conrad.sweatman@winnipegfreepress.

mb.ca Conrad Sweatman is an arts reporter and feature writer. Before joining the full-time in 2024, he worked in the U.

K. and Canadian cultural sectors, freelanced for outlets including , and . Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism.

If you are not a paid reader, please consider . Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

World Building as Radical Imagination: A Projection Mapping Installation Evan Tremblay and Mahlet Cuff ● Poolside Gallery, 100 Arthur St. ● To May 9 ● Wednesdays to Fridays, 1-5 p.m.

Conrad Sweatman is an arts reporter and feature writer. Before joining the full-time in 2024, he worked in the U.K.

and Canadian cultural sectors, freelanced for outlets including , and . Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider .

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support. Advertisement Advertisement.

Entertainment

Utopian dance

The latest exhibition at Poolside Gallery started out as a bit of a lark. “I was making a joke to a friend months ago, I was like, ‘What if I [...]