For a second consecutive year, Wall Street gave investors plenty of reason to smile. When the curtain closed on 2024, the ageless Dow Jones Industrial Average ( ^DJI 0.80% ) , broad-based S&P 500 ( ^GSPC 1.

26% ) , and innovation-inspired Nasdaq Composite ( ^IXIC 1.77% ) had respectively rallied by 13%, 23%, and 29% for the year, and hit multiple record-closing highs along the way. But as history has shown, Wall Street's major stock indexes don't move up in a straight line.

Investors are constantly on the lookout for predictive tools and data points that might signal a shift in the Dow Jones, S&P 500, and Nasdaq Composite and give them a competitive advantage. Even though no such tool or metric exists that's 100% accurate in forecasting short-term directional moves in the major stock indexes, there are a small number of data points and events that have strongly correlated with moves higher or lower in the Dow, S&P 500, and Nasdaq Composite over time. While a strong argument can be made that a historically pricey stock market is the biggest concern for investors, a first-in-90-years shift in another monthly reported economic data point may take the cake.

U.S. money supply last did this in 1933 The correlative data point in question that should be raising eyebrows on Wall Street is U.

S. money supply . While there are five different measures of money supply, the two that tend to earn the most attention are M1 and M2.

The former takes into account cash and coins in circulation, demand deposits in a checking account, and traveler's checks. M1 is essentially money that can be spent by consumers on the spot. Meanwhile, M2 factors in everything within M1 and adds in money market accounts, savings accounts, and certificates of deposit (CDs) below $100,000.

This is still money consumers can spend, but it requires more effort to get to. It's also the specific money supply measure that's cause for concern on Wall Street. Normally, the M2 chart slopes up and to the right.

This is to say that as the U.S. economy has grown over time, money supply has also increased, which reflects the need for more cash in circulation to facilitate transactions.

But in those exceptionally rare instances throughout history when M2 has endured notable declines, it's spelled trouble for the U.S. economy and stock market .

US M2 Money Supply data by YCharts . Based on data reported monthly by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, M2 clocked in at $21.448 trillion in November 2024, which is down from an all-time peak of $21.

723 trillion in April 2022. This represents a modest drop off of 1.26% from the all-time high.

But between April 2022 and October 2023, M2 money supply declined by a peak of $1.06 trillion, or 4.74%.

This marked the first time since the Great Depression that M2 had dipped by more than 2% on a year-over-year basis. However, this historic drop-off in M2 only tells part of the story. For example, fiscal stimulus during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic caused M2 to jump by more than 26% on a year-over-year basis .

The 4.74% decline witnessed between April 2022 and October 2023 might be just a form of mean reversion after the fastest expansion of money supply dating back more than 150 years. Furthermore, M2 has reversed course since October 2023 and is now growing on a year-over-year basis.

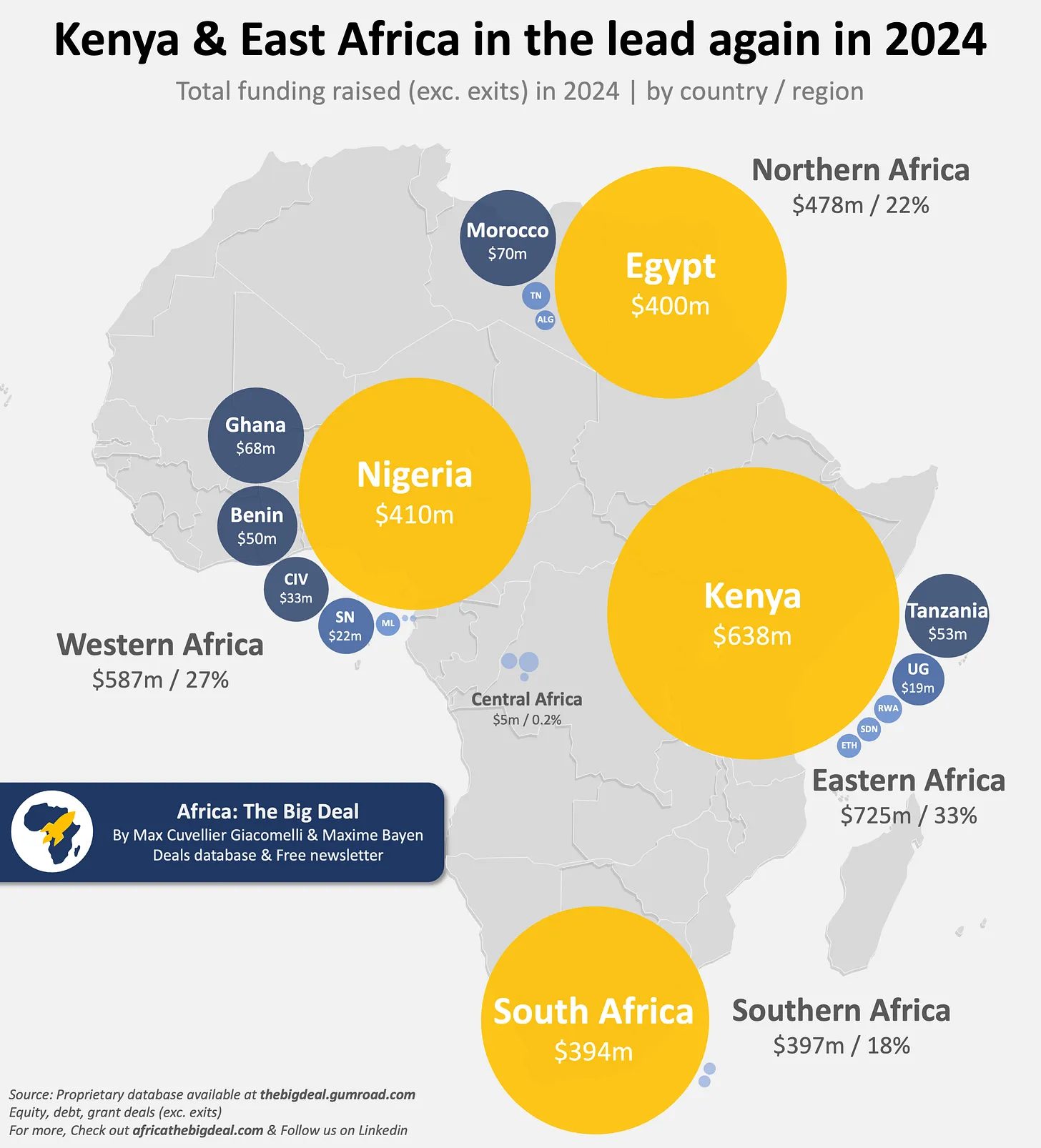

As noted, an increase in money supply typically accompanies a healthy economy. Nevertheless, sizable year-over-year drops in M2 have a flawless track record of foreshadowing trouble for the economy. The chart you see above, which was posted on social media platform X by Reventure Consulting CEO Nick Gerli in March 2023, examines the correlation between year-over-year declines of at least 2% in M2 and the performance of the U.

S. economy dating back to 1870. Over the last 155 years, there have been only five occurrences when M2 has dipped by at least 2% on a year-over-year basis : 1878, 1893, 1921, 1931-1933, and 2023.

Here's the kicker: All four prior instances correlate with economic depressions and double-digit rates of unemployment for the U.S. economy.

The asterisk to this correlative data is that the fiscal and monetary policy tools available today differ greatly from what could be done in the late 1800s or early 1900s. For instance, the Federal Reserve didn't even exist in 1878 or 1893. Meanwhile, the knowledge the central bank now has makes a depression unlikely in the modern era.

Despite this asterisk, there's concern that a dip in M2 amid a period of above-average inflation will cause consumers to put off discretionary purchases. This can lead to an economic downturn that eventually weighs on corporate earnings. According to an analysis from Bank of America Global Research from 1927 through March 2023, around two-thirds of the S&P 500's drawdowns occur after, not prior to, a recession being declared.

History works both ways -- and it strongly favors long-term investors Based solely on what history tells us, the new year could bring volatility and a sizable correction to the Dow Jones Industrial Average, S&P 500, and Nasdaq Composite. But the thing to understand about history is that the outlook for stocks can change dramatically depending on your investment horizon. For example, the analysts at Crestmont Research have been updating a data set for years that examines the rolling 20-year total returns, including dividends, of the benchmark S&P 500 since the start of the 20th century.

Although the S&P didn't officially exist until 1923, Crestmont was able to locate its components in other indexes in order to back-test total return data to 1900. Doing so produced 105 rolling 20-year periods, with ending dates from 1919 through 2023. What Crestmont found was that, inclusive of dividends, the S&P 500 has generated a positive total return in 105 out of 105 rolling 20-year timelines .

If an investor had, hypothetically, purchased an S&P 500 tracking index at any point from 1900 through 2004 and simply held that position for 20 years, they'd have made money every single time. A data set published on X in June 2023 by Bespoke Investment Group provides even more compelling evidence of how important patience and perspective are on Wall Street. As you can see in the table above, the researchers at Bespoke calculated the calendar-day length of every bear and bull market in the S&P 500 dating back to the start of the Great Depression in September 1929.

According to Bespoke's calculations, the 27 S&P 500 bear markets over 94 years lasted an average of just 286 calendar days, or 9.5 months. Further, the longest bear market on record, which occurred in the mid-1970s, stuck around for only 630 calendar days.

On the other side of the aisle, the typical S&P 500 bull market since the very late 1920s has endured for 1,011 calendar days , or roughly two years and nine months. Additionally, over half (14 out of 27) of all bull markets, including the current bull market if extrapolated to present day, have lasted longer than the lengthiest S&P 500 bear market. Regardless of how scary short-term economic data may be, history undeniably favors long-term investors.

.