Santa Fe, a city with more than 250 art galleries and dealers, long has traced much of its economic vitality — and its identity — to its visual arts scene. Forbes magazine labeled it the third-largest art market in the country, behind only New York City and San Francisco, in a February 2024 report — a designation repeated often by a variety of media outlets, including CNN. Travel + Leisure named it the seventh-best city in the world for art lovers in 2022, ahead of destinations such as Seattle, Berlin and Milan.

Most recently, the Meadow School of the Arts at Southern Methodist University in Dallas ranked Santa Fe the nation's most "arts-vibrant" medium-size community in the U.S. in its annual Arts Vibrancy Index, which includes performing arts and cultural institutions as part of its formula.

While many in the local art market point to signs that business is booming — or at least solid at a time when the global art market has seen declines — others view the city’s lofty standing with a dose of skepticism, recalling past decades when Santa Fe seemed to be in its peak period of making and marketing artwork. Ivan Barnett, the former longtime creative director of Patina Gallery in Santa Fe, argues the numbers simply don’t add up. “This idea that it’s the third-largest art market in the [country]? It’s not true,” he said, noting the city’s population is only about 90,000 people.

“It’s not big enough to claim that.” Even though the local arts scene remains robust, especially for a city with a relatively small population, Barnett said, it is not scaling the same economic heights it was 30 or 40 years ago, when Santa Fe style was all the rage — a period he refers to with a hint of derision as “the Ralph Lauren era.” It was a time when Canyon Road was a beehive of activity, especially during Friday evening gallery walks, and the sidewalks were teeming with wealthy Texans and Californians.

“There was a time in the ‘80s and ‘90s when Santa Fe was such a hot destination, anybody and everybody could get into [the art business] and sell stuff,” he said. “That’s changed.” Sandy Zane, a co-owner of Zane Bennett Contemporary Art and form & concept, both in the Railyard area, said she thinks Barnett is right in a lot of respects.

Santa Fe’s art scene no longer attracts the kind of national and international media attention it did during that high-water mark, she said. That’s unfortunate, she added, noting the city’s rich art history and the number of esteemed art figures who have lived here and continue to live here. “Having those kinds of prestigious artists choosing to live here” is significant, she said.

“If you go to a party in Santa Fe, you have no idea the kind of people you might meet, maybe a board member from the Whitney Museum [of American Art in New York City] or the Guggenheim [Museum, also in New York]. There are folks who come here to be under the radar.” Zane said the city doesn’t do enough to market itself as a gathering place for folks like that.

“I don’t know exactly what the right kind of vehicle for that action would be," she said, "but we still have an unbelievable number of artists who have made their mark here, and we deserve that kind of recognition.” A recent report indicates the global art market has seen a slowdown in the last couple of years, which likely has impacted Santa Fe sales. The Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report, released last week, says global art sales dropped 12% in 2024, the second year of slowing sales after a strong post-pandemic recovery.

The report notes the U.S., which led the market with 43% of sales, saw a smaller annual decline of 9%.

But there is little to no hard data examining how much art is sold in Santa Fe on an annual basis, and there seems to be no consensus about how the city's art galleries are faring these days. Ray Nowicki, who owned the Ahmyo River Gallery at 652 Canyon Road for six years before leasing the space earlier this month to another operator, said the industry has had to contend with several hurdles over the past several years. Topping the list is the coronavirus pandemic, when galleries and most other businesses were forced to shut down for several months, followed by runaway inflation that reduced the buying power of many Americans.

“Every few years, it seems to be something coming up that limits a fantastic season,” he said. Connie Axton, the owner of Ventana Fine Art, at 400 Canyon Road, said her business has managed to hold its own in recent years in the face of challenges, including the pandemic. “But it’s tough right now,” she said.

Lisa Stewart Keating, a self-proclaimed champion of the local art scene and executive director of the Santa Fe Gallery Association, acknowledged the pandemic took a toll, with the organization's members dwindling to just 30. However, she said, a majority of the members experienced record-breaking years when the COVID-19 shutdowns were lifted and in-person business resumed. The association doesn’t aggregate statistics for the local art market, she said, but it does monitor the figures provided by Tourism Santa Fe and the Hiscox Group, an insurance company that issues an annual online art trade report.

Anecdotal information from members is another important indicator, Keating said, and the returns that have come her way have been positive. “We are a resourceful and resilient bunch,” she wrote in an email. “As national and global events present challenges, gallerists react with new strategies to reach clients and cultivate new markets.

Right now, we are seeing a surge in art fair participation with robust sales.” As evidence of the strength of the local art market, Keating pointed to post-pandemic membership numbers. By 2021, the association had rebounded to 59 members.

Today, she said, it boasts a roster of more than 100 members — more than three times the number from the pandemic era. Nocona Burgess, a Comanche painter who relocated to Santa Fe from Oklahoma in the 1990s, said he, too, believes doubts about the city's status as a visual arts destination are overstated. "I still feel like I get a lot of people to come in from other states," he said.

He recalled showing his paintings at exhibitions in Texas and Oklahoma after he moved to Santa Fe, and said his work did not sell as well in those galleries as it does in his adopted hometown. Randy Randall, executive director of Tourism Santa Fe, the city of Santa Fe's tourism bureau, acknowledged some local gallery owners may be dissatisfied with the state of the market. But that’s always going to be the case, he said, even in times when business seems to be booming.

“Do they sell enough art? I don’t think you’ll ever find that they do,” he said, chuckling. Randall believes Santa Fe is attracting more visitors and gallery foot traffic than ever, he said, although he noted that doesn’t necessarily translate into art sales. “There are definitely more people in Santa Fe,” he said, citing the city’s population growth — more than 8% in the last decade and about 38% since 2000, according to census data — and his agency’s visitation numbers, which exceeded pre-pandemic levels in 2023.

“But I don’t think there are as many buyers as 20 years ago,” Randall said. Santa Fe visitors who are younger than 40 have changed, he said, adding fewer of those folks are art collectors, compared to previous generations. “Art is not as important to them as experiences,” he said.

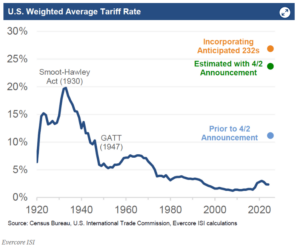

The election of President Donald Trump and the priorities and policies of his administration are the latest wild card for Santa Fe’s gallery owners, many of whom fear his tariffs and funding cuts for arts organizations and government agencies could have a strong negative effect on the art scene nationwide or, worse yet, trigger a recession. “It’s on everybody’s mind,” Axton said. “But we’ll keep our heads down and do the best we can do.

We’ve been through highs and lows before, and we will weather this.” Zane said she thinks the challenges posed by those shifting sands are very serious, noting the business world seems to be growing ever smaller. “Whether it happens in Greece or Zimbabwe, all of these things affect us in ways much [greater] than they ever have before,” she said.

Barnett — who recently launched Serious Play LLC, a consulting business for museums, galleries, artists and arts organizations — said it’s unclear how the art market locally and nationwide will be impacted by the changes. But he isn’t expecting any of them to be helpful. “We’re in for quite an interesting ride, and I don’t think culture matters at all to what’s going on in Washington,” he said.

“ ...

This is not an art-friendly atmosphere right now.” Gallery association members have taken a preemptive approach to the issue, Keating said, and have been talking across borders with arts organizations that may be impacted by new tariffs. “Our conversations aim to strengthen relationships and brainstorm effective ways to keep our markets strong,” she said.

“These times require cooperation, collaboration and creative solutions. Fortunately, our community has vast amounts of creativity to tap.” A range of factors affect local brick-and-mortar gallery sales, from rising rent and supply costs that drive up prices for artwork to competition from online marketers.

Burgess said he, like many of his fellow artists, has had to increase the asking price for his work in recent years as the cost of almost everything — including paint — has escalated. "You have to add in that cost. I kind of raise my prices every year," he said, noting a jar of paint that cost $6.

99 a few years ago now goes for $15.99. Keating agreed.

"While I haven't seen art prices rise as much as gas or groceries," she said, "I have seen art prices go up to meet the increasing costs of doing business." The online art market — which also has declined since a peak during the pandemic, according to the Art Basel and UBS report — certainly affects some gallery sales, Randall said. But he doesn’t think that segment of the market will replace in-person art shopping for a simple reason: “It’s not as much fun,” he said.

“If you really want the fun part of buying art, you’ve got to see it and visit it.” Randall remains optimistic about the future of the art market in Santa Fe, noting the occupancy rate of local hotels has been much higher for the past few years than it was before the pandemic. He also pointed to city lodgers tax collections that show remarkable growth over the last several years, aside from the COVID-19 era.

The strongest year before the pandemic was 2019, when collections reached almost $13 million. Over the last three years — 2022, 2023 and 2024 — collections have reached between $17.2 million and $18.

9 million each year, according to his agency. “If we can maintain that, we’re in great shape,” Randall said. One of the things that has allowed the Santa Fe art market to remain healthy is its diversity of styles, he said.

Instead of being regarded as the capital of a particular genre — such as Scottsdale, Ariz., with its Western art or Charleston, S.C.

, with oil paintings of shady plantations featuring trees draped in Spanish moss — Santa Fe offers art lovers almost every kind of art imaginable. Burgess speculated much of the art sold in Santa Fe is attractive to out-of-towners specifically because it was purchased here. "Maybe it sounds more exotic to say, 'I bought it in Santa Fe, not Fort Worth,' " he said.

While the variety of art offered citywide might be a draw, “the best [galleries] do not have something for everybody," Barnett said. "I’m a purist that way.” Many folks have a romanticized notion of what it takes to run an art gallery in Santa Fe, he said, noting the work requires a serious commitment.

At its best, he added, it can be a rewarding business, especially for those who approach it like a calling and develop a clear vision for what they want their gallery to be — and the kind of clientele they hope to attract. “I think the best galleries and the best museums have a distinct curatorial vision to them, and it’s not something everybody can do,” he said. Barnett said he sticks to the premise that gallery owners should believe in the style of work they are promoting or, better yet, in the artists whose work they feature.

If they successfully develop an identity and tell their story — separating themselves from hundreds of competitors — commercial sustainability will follow, he said. That’s the message he is trying to get across to his clients through Serious Play, his new venture, which aims to help artists and venues enhance their storytelling capacity and realize sustainable growth. Barnett, who was known for the elaborate and provocative ways in which he drew attention to the Patina Gallery during his time there, said he has nothing but respect for anyone who tries to run an art gallery in the crowded Santa Fe market.

But he argues having a passion for the art itself is the most important element. Zane said making the decision to open a gallery in Santa Fe is akin to taking a leap of faith. In her experience, that has not been a bad thing.

“I have always been optimistic, and I’ve jumped off an awful lot of cliffs in my life,” she said. “So far, I haven’t hit the ground.”.

Business

Up for interpretation: Data says art market booming; gallerists paint different picture

“This idea that it’s the third-largest art market in the [country]? It’s not true,” Ivan Barnett, the former longtime creative director of Patina Gallery.