Lawmakers in Oregon and Washington are considering whether striking workers should receive unemployment benefits, following recent walkouts by Boeing factory workers, hospital nurses and teachers in the Pacific Northwest that highlighted a new era of American labor activism. Oregon's measure would make it the first state to provide pay for picketing public employees — who aren't allowed to strike in most states, let alone receive benefits for it. Washington's would pay striking private sector workers for up to 12 weeks, starting after at least two weeks on the line.

“The bottom line is this helps level the playing field,” said Democratic state Sen. Marcus Riccelli, who sponsored Washington's bill. “Without a social safety net during a strike, workers are faced with tremendous pressure to end the strike quickly or never go on strike in the first place.

” But the bills are raising questions about how they would affect employers, especially amid economic uncertainties tied to federal funding cuts and tariffs imposed by President Donald Trump. “It’s inappropriate to unbalance the bargaining table in a way that forces employers to pay for the costs of a striking worker,” Lindsey Hueer, government affairs director with the Association of Washington Business, told senators during a committee hearing in February. “Unemployment insurance should be a safety net for workers who have no job to return to.

" So far only two states, New York and New Jersey, give striking workers unemployment benefits. Senate Democrats in Connecticut have revived legislation that would provide financial help for striking workers after the governor vetoed a similar measure last year. Benefits bills advance but face opposition The measures in Washington and Oregon have been passed by the state Senate of each and are now in the House.

The Washington bill faces its final committee hearings on Friday and Monday. The Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit, pro-labor think tank in Washington, D.C.

, has studied the effects of giving unemployment benefits to striking workers and found it to be good for workers and employers alike, said Daniel Perez, state economic analyst for the organization. First, he said, lengthy strikes are extremely rare. More than half of U.

S. labor strikes end within two days — workers wouldn't receive pay in those cases — and just 14% last more than two weeks. Second, the policy costs very little — less than 1% of unemployment insurance expenditures in every state that has considered legislation.

Bryan Corliss, spokesperson for the Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace union, told The Associated Press that the big winners would be low-wage workers. “If low-wage workers had the financial stability to actually go on strike for more than a day or two without risking eviction, we believe that would incentivize companies to actually come to the table and make a deal," he said. During a hearing in the Washington House labor committee last week, several Republican lawmakers tried to amend the bill to require striking workers to look for other jobs or to shorten the time covered from 12 weeks to four.

The Democratic majority shot those ideas down. Republican Rep. Suzanne Schmidt said the bill might be good for workers, but it would hurt employers.

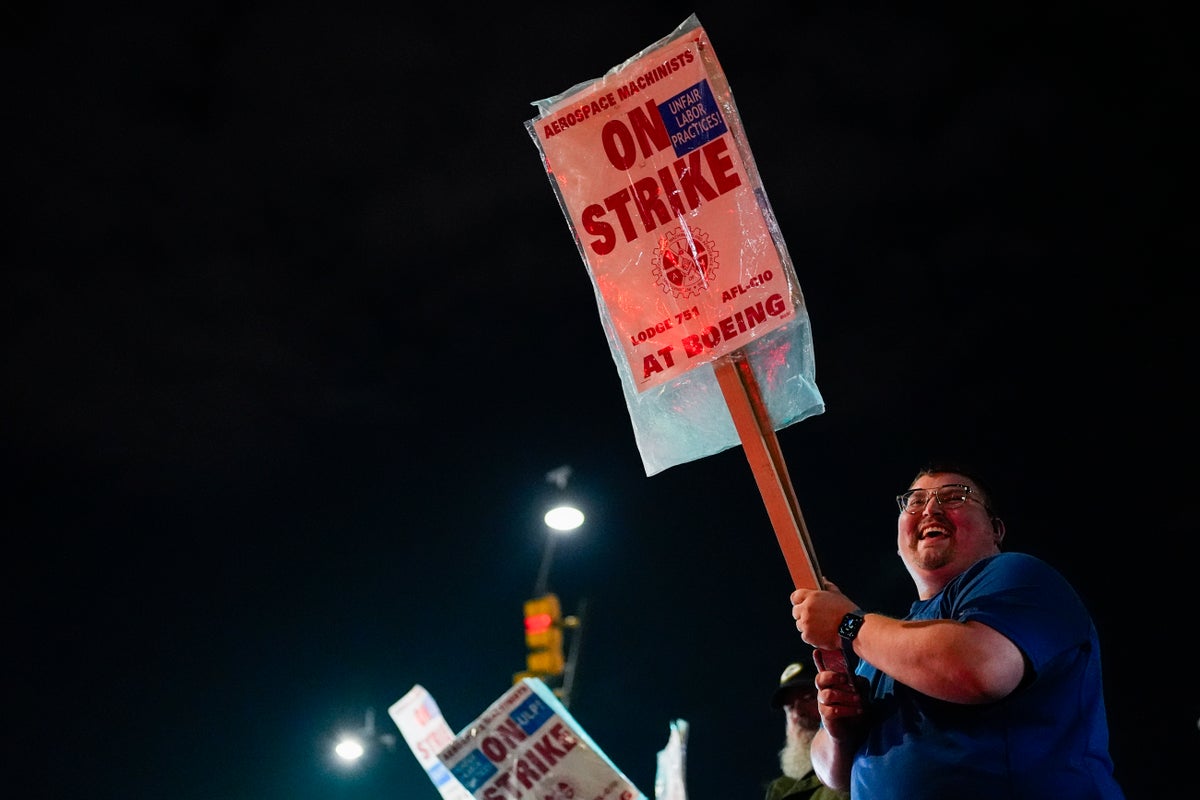

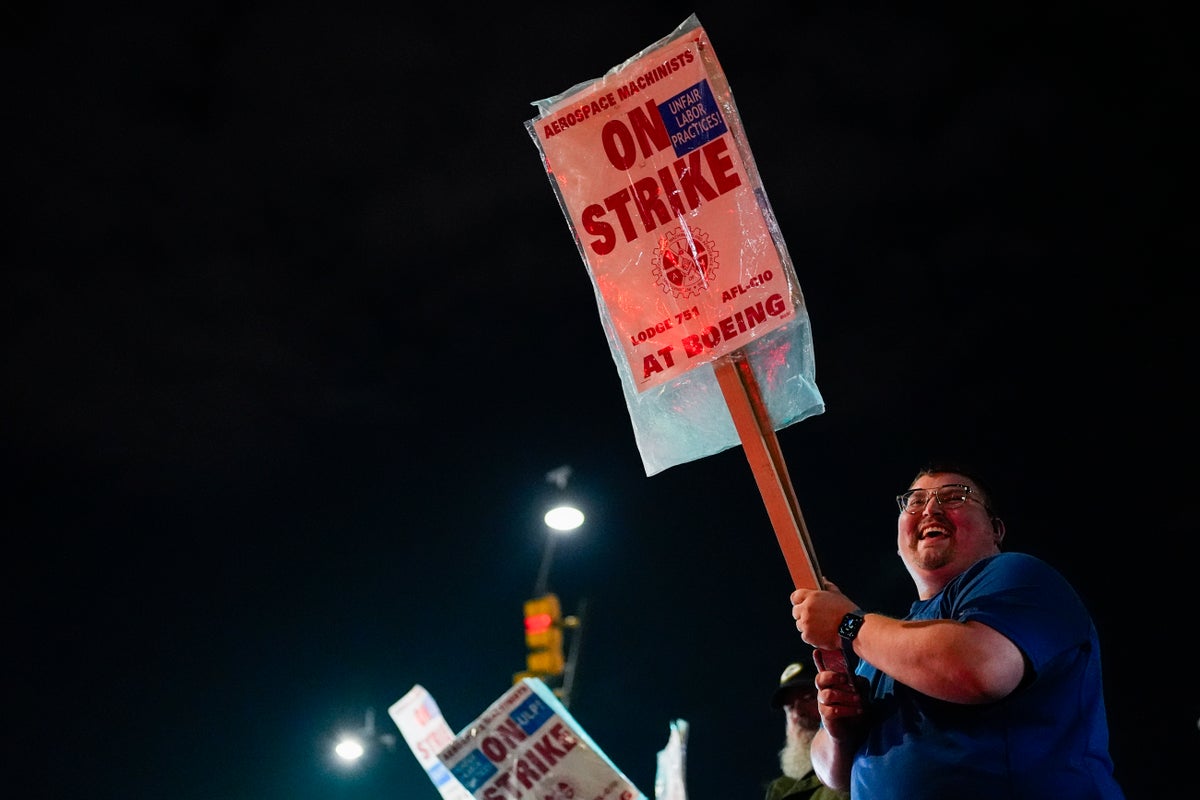

“We’ve seen instances of this with the Boeing strike last year for the machinists," she said. "We had 32,000 people on strike at the same time and if this had been in play it would have cost millions of dollars to cover those workers. Boeing did actually lose billions having the workers on strike for several months.

” The Oregon bill, which also would make striking workers eligible for unemployment benefits after two weeks, sparked a similar debate, both among Democratic and Republican lawmakers as well as constituents, with hundreds of people submitting written testimony. The state has seen two large strikes in recent years: Thousands of nurses and dozens of doctors at Providence's eight Oregon hospitals were on strike for six weeks earlier this year, while a 2023 walkout of Portland Public Schools teachers shuttered schools for over three weeks in the state's largest district. The Oregon Senate passed the measure largely along party lines, with two Democrats voting against it.

On the Senate floor, Democratic Sen. Janeen Sollman said she worried about the effect on public employers such as school districts, which “do not have access to extra pots of money.” Private employers pay into the state's unemployment trust fund through a payroll tax, but few public employers do, meaning that they would have to reimburse the fund for any payments made to their workers.

Democratic Sen. Chris Gorsek, who supported the bill, argued it wouldn't cost public employers more than what they've already budgeted for salaries, as workers aren't paid when they're on strike. Also, those receiving unemployment benefits get at most 65% of their weekly pay, and benefit amounts are capped, according to a document presented to lawmakers by employment department officials.

“Unemployment insurance is partial wage replacement, so unemployment insurance in and of itself is not an additional cost to the employer," Gorsek said. “In fact, the only way Senate Bill 916 would yield additional cost for what was already budgeted by the employer is if the employer decided to hire replacement workers.” ___ Rush reported from Portland, Oregon.

Associated Press writer Susan Haigh in Hartford, Connecticut, contributed..

Top

Unemployment benefits for striking workers being considered in Oregon, Washington

Lawmakers in Oregon and Washington are considering whether striking workers should receive unemployment benefits