E ducation is the cornerstone of national development. Yet, in Pakistan, education financing continues to fall short of what is necessary to meet the country’s growing needs. It is in this context that the recent Public Financing in Education Sector 2019-23 report, produced by the Pakistan Institute of Education, deserves commendation.

By collating scattered education financing data from across federal, provincial and regional levels, the PIE has provided a rare, holistic view of where Pakistan stands in public investment in education. This effort is a significant step forward in ensuring transparency and accountability, equipping policymakers with the insights needed to make informed decisions. Pakistan’s allocation to education has hovered between 11 and 13 per cent of the national budget over the past four years.

This falls significantly short of international benchmarks i.e. 15-20 per cent of public expenditure.

UNESCO recommends allocating four to six per cent of GDP to education. Pakistan lags far behind not just globally but regionally. Other South Asian countries like Nepal, Bhutan, and India spend much higher proportions of their GDP on education, placing Pakistan among the lowest in terms of public investment in this sector.

Where Pakistan has not been successful in spending around two per cent of its GDP on education for the past 20 years, India has consistently spent over four per cent of its GDP on education. Bhutan, on the other hand, has been allocating over seven per cent of its GDP to fund public education, making it one of the highest spenders on education in South Asia. The chronic underfunding in Pakistan is not just a failure to meet global standards but also a missed opportunity to reap the socio-economic dividends of stronger education systems.

This low spending is compounded by inefficiencies and underutilization, with only 94 per cent of the education budget being spent, leaving critical resources untapped. The unspent funds, a symptom of bureaucratic delays and poor planning, are often redirected to other sectors, further depriving education of the support it desperately needs. One of the most glaring issues highlighted is the imbalance between recurring and development expenditures.

A staggering 88 per cent of the education budget is consumed by recurring costs, such as salaries, leaving only 12 per cent for development. This allocation reflects a system geared towards maintaining the status quo rather than transforming education through infrastructure improvements, teacher training or digital learning tools. Without a significant shift towards development spending, Pakistan will struggle to address the systemic inequities and quality deficits that plague its education sector.

Another pressing issue is the stagnation of the devolution process when it comes to education. The 18th Amendment devolved significant powers to provincial governments. However, this decentralisation has largely stopped at the provincial level.

The lack of further devolution to district, tehsil and school levels has led to a disconnect between grassroots stakeholders and decision-making processes. Empowering local actors, including school management committees, teachers and community representatives, is essential for crafting education policies that are responsive to local needs and realities. A staggering 88 per cent of the education budget is consumed by recurring costs, such as salaries, leaving only 12 per cent for development.

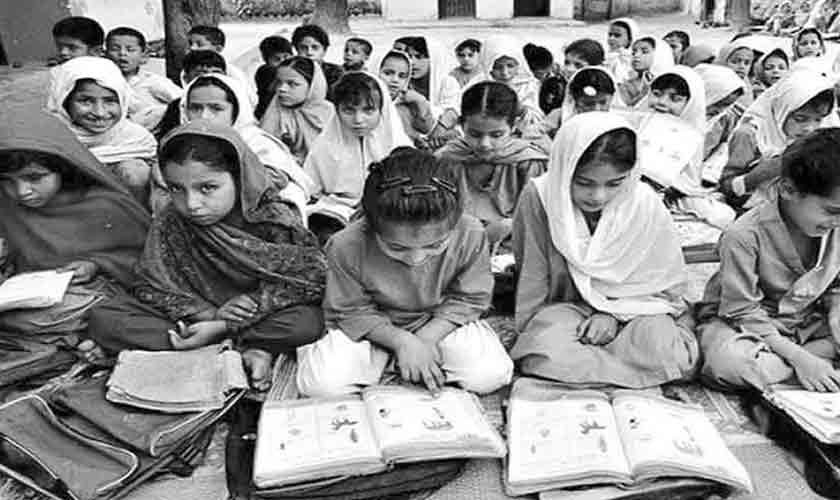

Regional disparities exacerbate these challenges. Education in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa remains chronically underfunded. This inevitably translates into an acute lack of opportunities for children in underserved areas, perpetuating cycles of poverty and underachievement.

Another critical concern is the neglect of sub-sectors like early childhood and secondary education. Early childhood education is widely recognised as one of the most cost-effective ways to improve long-term learning outcomes, yet it receives minimal investment in Pakistan. Similarly, secondary education, which is vital for preparing skilled youth for the 21st-Century labour market remains underfunded.

These gaps highlight a lack of strategic planning in education financing, with short-term needs often overshadowing long-term benefits. Despite Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif announcing an education emergency earlier this year, challenges vis-à-vis financing reflect a clear lack of priority when it comes to the expansion of education in Pakistan. Increasing the education budget to align with global standards is not merely important for Pakistan to meet its international commitments; it is a necessity for the country to develop and prosper.

However, raising the budget alone is insufficient. Ensuring that these funds are spent efficiently and equitably is equally critical. Implementing real-time tracking systems for budget disbursement and expenditure can help reduce inefficiencies and ensure that every rupee allocated to education serves its intended purpose.

A more balanced approach to spending is also essential. Recalibrating the budget to allocate a greater share to development activities can catalyse meaningful change. Investments in infrastructure, teacher capacity building, skill-based education at every stage of education and digital education tools are urgently needed to improve both access and quality.

Public-private partnerships can play a crucial role here, bridging resource gaps and introducing innovative solutions to persistent challenges. Addressing regional inequities in education financing requires bold, targeted actions. The federal and provincial governments must work collaboratively to design funding models that reflect the unique needs of each region.

Special focus should be given to Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where educational outcomes lag far behind national averages. Equity, rather than uniformity, should guide policy decisions, ensuring that all children, regardless of where they are born, have access to quality education. It is equally important to advance the devolution process beyond the provincial level.

Local actors must be empowered to shape policies and utilise resources effectively, ensuring that decisions are grounded in the realities of classrooms and communities. Grassroots stakeholders, such as district education officers, parent-teacher associations and school heads, need meaningful participation in decision-making. This is not just a matter of governance but a strategy to make education policies more inclusive and impactful.

Education in Pakistan cannot be treated as an expenditure; it is an in vestment in human capital. Policymakers, civil society and development partners must unite around a shared vision by adopting bold reforms, prioritising strategic investments and empowering grassroots stakeholders. Investing in education is the most effective pathway to social and economic prosperity.

The writer is the executive director of the Society for Access to Quality Education and the national coordinator for the Pakistan Coalition for Education. She tweets at @Zehra2576.