Welcome to a controversial topic. This writer normally keeps things short and sweet—concise, and usually with no opinions shared. I first created “THEN & NOW” 30 years (and three newspapers) ago to offer bite-sized, tempting morsels of history.

But this story is complicated and will take longer to tell. So, stay with me. It will include the opinions of historians, sometimes with differing views.

It will also include my own views, some controversial. For example, as a writer, editor, and researcher with 50 years of experience, I have learned over the last decade that Native American communities have the best perspective to tell their history. So, as a historian of mostly European descent whose maternal ancestors settled in Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1634, I offer this narrative with respect and admiration toward all Native American communities.

Now, on to the topic represented by the old postcard shown above. The dolomite monument inscription was clearly readable when the postcard was published in 1905. Over the decades, the words have been eroded by the tears of time.

Most of the letters can no longer be seen. Some believe that Mother Nature had a reason for the gradual erasure.In 1904, the women of the Thursday Morning Club, one of Great Barrington’s civic organizations, installed the so-called Indian Fordway monument near the Bridge Street Bridge.

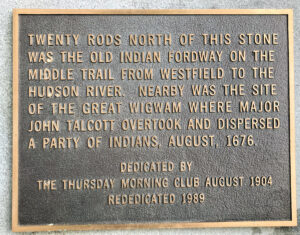

The club has been a generous benefactor to countless groups and individuals since it was founded in 1892. When the monument became unreadable by the 1980s, the highly respected club installed a replacement bronze plaque with the exact same wording at the monument’s base. It reads:Twenty rods north of this stone was the old Indian Fordway on the middle trail from Westfield to the Hudson River.

Nearby was the site of the Great Wigwam where Major John Talcott overtook and dispersed a party of Indians, August, 1676. Dedicated by the Thursday Morning Club August 1904. Rededicated 1989.

Before considering the above statement, we must first discuss the subject of “King Philip’s War.”Relentless European encroachment on tribal lands in 17th-century New England eventually resulted in Native American hostility. This culminated in 1675 with the start of King Philip’s War.

Wampanoag Indian sachem Metacom (called King Philip by European settlers) united warriors from several tribes, including the Narragansetts, and attempted to drive the colonists from New England. More than half of the towns and villages in New England became involved in the conflict.Initially, the Natives had some success, but it was short lived.

Metacom was beheaded on August 12, 1676. The war in southern New England largely ended with his death and continued in northern New England until the signing of the Treaty of Casco Bay in 1678. Based on the percentage of the overall population killed, King Philip’s War is now considered the bloodiest conflict in North American history.

An additional clash came several days after Metacom’s death. And it may have happened in the wilderness of the Berkshires along the Housatonic River (referred to as the Ausotiunnoog River in early records). Back then, there were no colonial settlements here, only a few seasonal Dutch and English fur trappers.

But where exactly did this specific battle take place? Was it in what is now Great Barrington? One 19th-century writer suggested Stockbridge. Others, Sheffield. Or perhaps northwest Connecticut?In 1889, the Berkshire Courier published an article about the Housatonic River attack, likely pulling information from earlier primary and secondary sources.

The article read, in part:Major John Talcott with a detachment of Connecticut militia, and a body of friendly Indians, was stationed at Westfield, then an outpost far into the wilderness. One August evening this officer was informed by scouts that the fresh trail of about two hundred Indians had just been discovered a few miles south of his post, and though his force was somewhat inferior in number, he determined to set out in pursuit..

. the remnant of the Narragansett tribe fled westward, hoping to find an asylum with the Mohawks..

. [near Albany, New York]Meanwhile, upon arrival at the Housatonic River, the Narragansetts proceeded more leisurely and camped on the western bank. Here, they were apparently discovered by Talcott late in the afternoon of the third day’s march.

Fatigued, Talcott decided to wait until morning to attack. Early the next day, Talcott launched his assault. His troops were quickly discovered by an Indian scout who yelled out a warning.

The Natives bravely resisted the attack, but were soon overcome. It was reported that 45 Natives were captured and 25 were killed or wounded. The rest successfully escaped to the west.

Some historians believe that Talcott exaggerated the kill count in his report. Talcott reported the loss of only one man on his side of the battle—a Mohegan Indian fighting with the soldiers.Some early reports suggest that the Natives were headed toward an Indian encampment near Albany.

Others dispute this. More on that later.Getting back to the stone monument and bronze plaque.

The wording is ripe with challenges. Let’s take them one at a time.1.

Great WigwamBecause some Native American artifacts were once found near the present-day First Congregational Church in Great Barrington, early residents assumed that the legendary Great Wigwam (home of tribal leaders) was once located there. This is not likely. Artifacts are still found in numerous locations throughout southern Berkshire County.

The late historian James Parrish believed the Great Wigwam was located along the Housatonic River, but north of downtown. There is a significant ancient site there, but its location is secret. The late Lion Miles of Stockbridge, a respected historian of Stockbridge-Munsee culture, along with other local researchers, believed that the more likely site of the Great Wigwam was Vosburg Hill, near Wyantenuck Country Club, off West Sheffield Road.

This was also likely the home of tribal sachem Umpachene and is a spacious site overlooking the valley of the Green River. It is located within an area known as the Skatekook Reservation, some of which was retained by local Native Americans for another hundred years, after most were relocated to the Stockbridge Mission in the 1730s.2.

Indian FordwayThere were several Native American paths/fur trade routes from the Connecticut River valley to Albany. One went through Stockbridge. One of the most prominent trails went through the present-day Water Street Cemetery along State Road, near the Pizza House in Great Barrington.

Where the trail went from there changed over the decades and is still debated.The trail was widened and adapted into a military road in 1758 by General Jeffery Amherst so his troops could move more easily toward their destination of Fort Carillon (now Fort Ticonderoga) near Lake Champlain during the French and Indian War. By the time Amherst arrived here, a “Great Bridge” had been established across the Housatonic River at the site of the present-day so-called “Red Bridge.

” General Henry Knox followed the same route (but in reverse) in early 1776 to deliver cannons and assorted weapons to discourage British occupation of Boston.Exactly when was the “Great Bridge” first erected over the Housatonic River? This is also debated, but sometime between 1737 and 1745. Meanwhile, the original trail continues along present-day East Street, and up Quarry Street heading south.

This later became a County Road, the south portion of which was discontinued by the early 20th century. Portions of the road can still be found near the power lines, and on Camp Eisner property. Some believe that this early trail also branched off toward the river.

In the years before the “Great Bridge” was built, the most likely crossing of the Housatonic was in the area referenced on the stone monument—a bit north of the present-day bridge near the former Searles High School. It is here that the river banks are low and gentle. Old maps also suggest the fordway was located here.

Two years before his death in 1904, town historian Charles Taylor was quoted in a newspaper referring to this old fordway. “A few years ago,” he said, “one could [still] see the indentation in the bank where the old wagon road, which followed the old Indian path closely, left the water.”In the 1950s and ‘60s, this portion of the river was dredged and partially rip-rapped, so there is no longer evidence of the fordway.

There was another Indian trail from Westfield that went southwest through northwest Connecticut and/or southern Sheffield. Stockbridge historian Lion Miles strongly challenged the belief that Talcott’s battle took place in what is now Great Barrington. A few years before his death, Miles explained to this writer, and also wrote, that later testimony by one of the fleeing Natives indicates that they were headed for an encampment near present-day Saugerties, N.

Y., not Albany. This, he explained, suggests they might have crossed the Housatonic River further south.

3. Talcott’s RaidThe stone monument and bronze plaque stated: “Nearby was the site..

. where Major John Talcott overtook and dispersed a party of Indians, August, 1676.”It is, perhaps, unfair to judge this statement written in 1904 in the context of today’s knowledge and understanding of history.

Several years ago, a few interested parties found fault with the monument, suggesting the word “dispersal” should read as “massacre.” One or two people complained to officials at town hall that the plaque should be removed. A Native American from east of the Berkshires—who claimed to have psychic abilities—stated his belief that Native children had been killed at the site.

Shortly thereafter, the bronze plaque was stolen. A local newspaper described the plaque theft more gently, with the carefully chosen alternative: “disappeared.”THEN: This bronze plaque was installed in 1989 when the wording on the Indian Fordway stone monument was no longer legible.

The plaque was stolen in 2022. Photo courtesy Great Barrington Historical Society.NOW: The eroding dolomite monument as it looks today.

Photo by Gary Leveille..

Top

THEN & NOW: The Indian Fordway Monument in Great Barrington

I first created “THEN & NOW” 30 years (and three newspapers) ago to offer bite-sized, tempting morsels of history. But this story is complicated and will take longer to tell. So, stay with me.