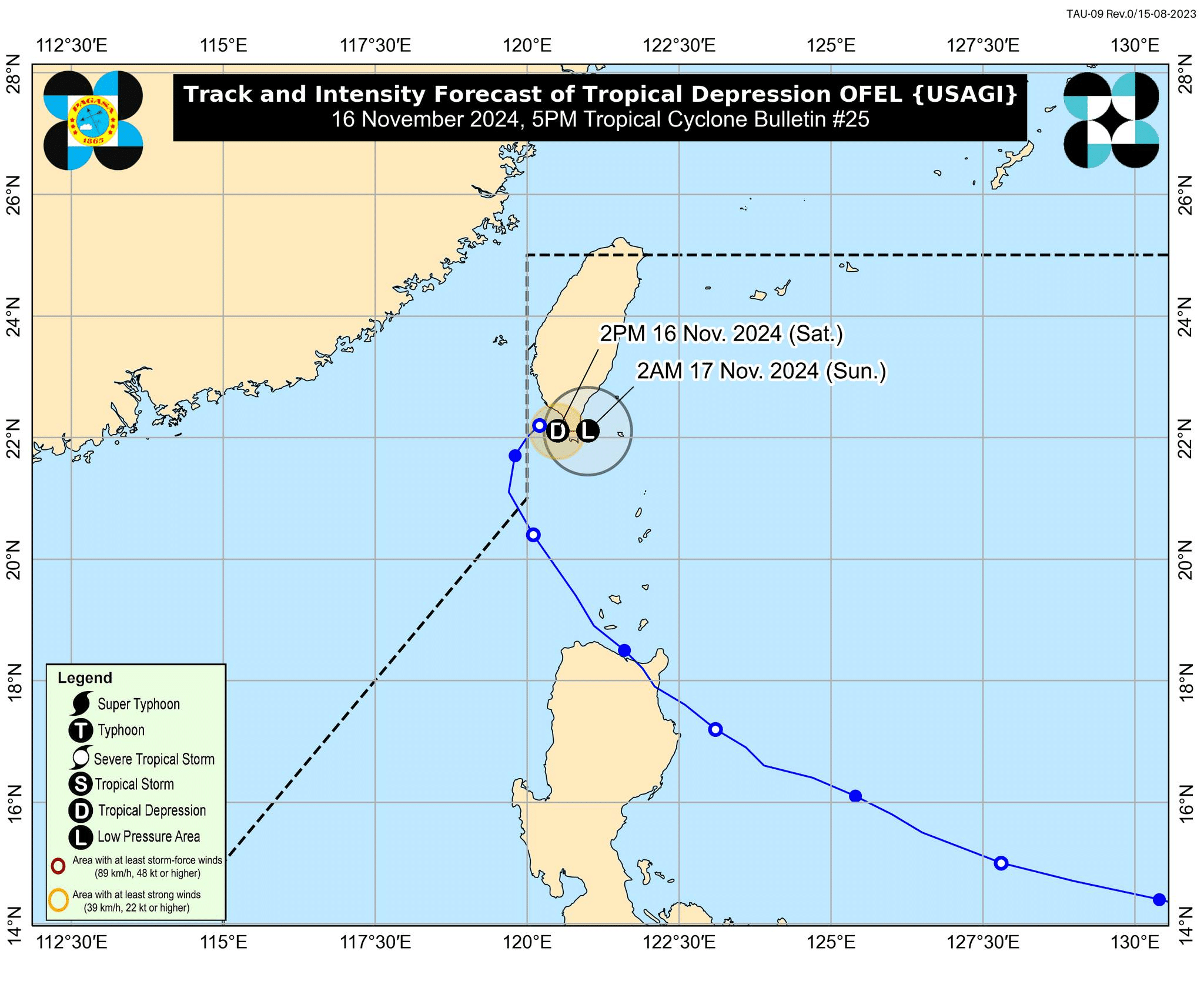

Bruce Dickinson stares out across a sea of 300,000 Brazilian faces, and a sea of 300,000 Brazilian faces stare back at him. What they see is a sweat-coated Englishman, blood running down his face, barely bothering to hide his anger. It’s Friday, January 11, 1985, and are playing the opening show of the 10-night megafestival, second on the bill under headliners Queen.

This is the biggest gig Maiden will ever play, and it should be a triumph. Except things aren’t going as planned. A local monitor engineer is messing up their sound, and Bruce is getting increasingly irate about it.

During , his fury spills over. Frustrated, he rips off the guitar he’s been playing, only to bash the instrument against his forehead, cutting it open. Blood begins to flow and he sees red in more ways than one.

“Fucking fix the sound. Don’t fucking stand there like a goldfish!” he yells at the hapless engineer, before smashing the guitar across the mixing desk. “I expect I looked like a raving lunatic,” Bruce wrote in his 2017 autobiography, , “which at that moment I was.

” As Bruce steps behind the amps to compose himself, a roadie gives him a message from the band’s formidable manager, Rod Smallwood. Can the singer squeeze the gash on his head to make more blood come out? It’ll look great. Smallwood isn’t wrong.

“Next day, the picture was front-page news: sweaty, bloodstained me, and 300,000 new Iron Maiden fans,” wrote Bruce. Onstage shit-fits aside, Rock In Rio is a ringing victory for Iron Maiden, and a marker of their escalating fame. It comes on the back of their pivotal fifth album, , released four months earlier, in September 1984.

That record remains one of the most ambitious albums Maiden have ever made. Lyrically and thematically, Powerslave saw them travelling from ancient Egypt to the very end of the 20th century and impending apocalypse, via Napoleonic Europe, World War II and the fevered dreamworld of a Romantic poet. Musically, its longer, more intricate songs – especially 13-minute closer – offered an early pointer to both Iron Maiden’s own future and the entire genre.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox! More importantly, Powerslave made Iron Maiden international superstars. The album, and the all-conquering World Slavery Tour, took them where no metal band had ever been before: not just Europe, the US and Japan, but South America and the Eastern Bloc too. Powerslave put Iron Maiden on the global stage, and they’ve never left it.

The 1980s was the decade that metal truly became a dominant cultural force, and Maiden were marching in lockstep with its rise. Their self-titled 1980 debut and the following year’s turned them into stars at home in the UK, but it was 1982’s – the first to feature Bruce Dickinson – and 1983’s that secured them a foothold in the US. That success didn’t come without some hard graft.

“We just toured: album, tour, album, tour, writing, recording, touring,” remembered in the documentary . “Even though we were young and fit and able, it was absolutely mad how many shows we did, how much recording we did in such a short period of time. But when it’s going well, you’ve just got to keep it going.

” The air of bulletproof confidence that surrounded Maiden extended to the prospect of continuing their red hot run of albums. “The truth is I didn’t really feel any pressure at the time,” Steve told the band’s official biographer, Mick Wall, of writing the follow-up to . “It wasn’t arrogance.

I just never worried about what we had done before or what other people – management, record companies, tour promoters, the music press – expected of us.” When Maiden decamped to Jersey in the Channel Islands in January 1984 to start writing the follow-up to , they had the wind at their backs, metaphorically and literally. Their HQ was Le Chalet, a cliffside hotel built to withstand the gusts whipping in from the sea.

“I swear the windows were bending half an inch from the Atlantic gale,” recalled Bruce in The History Of Iron Maiden. The band and their crew had booked out the whole hotel. The fact that it was freezing cold and out of season meant there would be no distractions.

At least that was the plan. “We were supposed to be there writing,” recalled Steve during a 2021 Tim’s Twitter Listening Party online playback session dedicated to . “I say ‘supposed to’, because mainly the first week or so we ended up getting pissed! We had the whole hotel to ourselves and it had a 24-hour bar.

You’ve got to get into the vibe of things, I suppose.” The allure of all-day drinking eventually wore off, and they got down to the matter in hand. Maiden weren’t the kind of band to carry unused songs over from previous albums, but they had ideas kicked around.

One of these was a song Bruce Dickinson had been working on during the tour in support of . This rough outline would eventually become ’s epic, seven-minute title track. “I was thinking about [occult-themed track] , and I was looking for something missing,” the singer told French magazine in 1984.

“In , there are all sorts of signs related to Hindu and Egyptian mythology about life and death. But there was something missing: the power of death over life, which is a theme you find very often in Egyptian mythology. I basically wrote while listening to , a cup of tea in one hand and bacon in the other.

” His bandmates were no less productive. Bruce and guitarist had struck up a writing partnership on , delivering soaring single and sparkling, samurai-inspired deep cut . In Jersey, they began working on a song that would prove to be one of ’s defining tracks, the razor-sharp .

The seeds for the song were sown one night when Adrian was doodling on his guitar in his hotel room and Bruce knocked on his door. “I played him the music. He started singing, and we had ” the guitarist told Mick Wall.

“We wrote it in about 20 minutes.” If that captured Maiden’s liquid energy, another song that began life in Jersey showcased the scale of their ambition. Steve Harris’s was shaping up to be a weighty, multi-part epic based on the lengthy 1798 poem of the same name by early 19th-century Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

It found the bassist using Coleridge’s original 625-line ode about a sailor cursed after killing an albatross at sea as the jumpingoff point for his own version of the kind of classic prog rock songs he loved as a kid. “Steve’s mad idea” is how Adrian Smith described the track that would stand as the first of Maiden’s true prog metal epics. By the time the band left the wind and rain of Jersey after six weeks in Le Chalet, they had most songs of the songs that would appear on in various stages of completion.

It was the raw clay of a new album. But it would take the heat of the Caribbean sun to bake it into something solid. There were worse places to make an album in the 80s than Compass Point Studios in the Bahamas.

had recorded the zillion-selling there in 1980, while everyone from the Rolling Stones to pop diva Grace Jones had enjoyed all the luxuries that Compass Point and its surroundings had to offer. Iron Maiden arrived there in the spring of 1984 to record with trusted producer Martin Birch. The latter was a wry and charming Englishman with a devilish side.

His nickname was ‘Pool Bully’ for the way he would sometimes shove unsuspecting bandmembers into the nearest swimming pool. He was also a karate fanatic, occasionally stopping sessions to practise his chops and kicks in the middle of the studio. One eventful evening found the producer and keen swordsman Bruce Dickinson embroiled in a ‘fencing vs karate’ duel to find out which was the most effective method of fighting (spoiler: it’s fencing).

The same relaxed mood that permeated their time in Jersey continued here. The Bahamas may have been considerably warmer and drier than the Channel Islands, but in other respects it wasn’t so different. “We ended up a bit stir crazy,” said Bruce in .

“So you get up to mischief. There was a bar down the road where you could drink frozen banana daiquiris that were lethal and play all day.” The bar in question was The Waterloo Club.

“We used to do a take and then Nicko [McBrain, drummer] would go, ‘Let’s go down the Waterloo,’” recalled Steve. “We’d go, ‘Oh no, not again..

. oh, alright then.’ Then we’d go down there and come back at six or seven in the morning.

It’d end up being a day off after that usually.” Martin Birch didn’t mind. In fact, he was sometimes the instigator of shenanigans.

The producer had a hellraising alter ego, ‘Marvin’, which would emerge after drinks had been consumed. “Marvin kind of appeared on nights off,” Martin, who died in 2020, explained in . “Or if Marvin appeared, it was a night off.

” One morning, he summoned Adrian into the studio to record a solo for the song . The guitarist had been drinking until the small hours with Martin and the rest of the band, and wasn’t exactly thrilled at the prospect of playing. “I was extremely hungover,” he told .

“We were out until three in the morning, and I went home thinking, ‘We’re not working tomorrow, we’ve gone too hard.’” Martin had other ideas. When Adrian arrived, he found him sitting in the control room with Robert Palmer, the suave singer most famous for 80s megahit , who lived near the studio.

Palmer was wearing pyjamas and a cravat. It turned out the producer had called on him after the rest of Maiden retired to bed and the two men had carried on drinking rum. “I had to do my solo for , and I had the shakes, but I just went, ‘Fuck it’,” Adrian told .

“I pulled off a solo and Robert Palmer was going, ‘That’s fucking great!’” Amid all the boozing and karate chopping, Maiden found time to actually make a record. They began putting meat on the bones of the songs they had come up with in Jersey. Bruce completed the lyrics to , the song he and Adrian had written in less than half an hour.

The title referred to the so-called Doomsday Clock, the symbolic countdown of how close humanity is to wiping itself out through nuclear war or other self-inflicted catastrophes. The singer piled on the apocalyptic imagery (‘ / ’), but while he might have delivered the song with lip-smacking relish, his contempt for ‘the killer’s breed’ behind it all was tangible. “It’s a song about the experience of war and about the romance of it and the horror of it and the two things together.

And the fact that, unfortunately, we’re repelled and fascinated by it,” explained Bruce in . If found Maiden staring down the real world, they retreated to more familiar ground elsewhere. , the album’s Steve Harris-penned opening track, was a barnstorming, Boy’s Own tribute to the RAF fighter pilots who took part in the Battle Of Britain during WWII.

The song would become enshrined as Maiden’s set opener on the subsequent World Slavery tour, preceded by Winston Churchill’s iconic “We shall fight them on the beaches” speech, as immortalised on 1985’s album (even Steve Harris has admitted that he wonders where the Churchill speech is whenever he hears the studio version). There was more historical action in the swashbuckling one-two of and , a pair of songs centred around sword fighting. Ironically, only the former was written by trained fencer Bruce Dickinson; the latter, inspired by the 1977 Ridley Scott movie of the same name, was a Steve Harris track.

, the album’s second (and less essential) Dickinson/Smith co-write, was a sequel of sorts to from , itself based on the mind-bending 1960s TV show of the same name. The punningly titled instrumental was as throwaway as its name suggested. Maiden saved the two heftiest songs for the end of the album.

itself was a monumental slab of Egyptian-themed metal, as imposing as a pyramid and mysterious as the Sphinx. On the surface, it was the tale of a Pharaoh both blessed and cursed by the power he wields, a living god destined to be sacrificed. “At the beginning of the song, the Pharaoh dies,” the singer told .

“At the end of the song, he’s still alive but a change has occurred. His spirit is still alive and tries to break free of his dead body.” The song was also the singer’s subtle commentary on Maiden’s own growing success.

“The tours were getting longer and crazier, and the expectations around us were astronomical by the time we came to ,” he said. “We were slaves to the power, whether musically or in terms of just chasing success. In fact, we were both.

” The last song Iron Maiden finished at Compass Point was the song that would close : . Steve Harris was still working on his seafaring magnum opus well into the recording sessions. “I knew that we had to get it done because we were getting through the songs a lot quicker than I thought we would,” the bassist said in .

“There was a bit of pressure to get it finished.” Eventually, he whittled the original poem’s 625 lines down to a mere 82 lines. There was just one snag: Bruce Dickinson still had to learn them.

“Steve had to hang the lyrics from the top of the wall all the way to floor, there were so many for Bruce to learn,” said Adrian. The finished track came in at a meaty 13 minutes and 45 seconds - by far the longest song Maiden had recorded to that point. “The funny thing is, no one actually thought it was 13 minutes long at all,” Steve told in 2008.

“We thought it was only eight or nine minutes long, maximum. When Martin Birch timed it at 13 minutes we were all like, ‘Fuckin’ ’ell, 13 minutes?!’” Bruce was a big fan of the song, despite its lyrical density. “I can remember all the words and have a cup of tea in the middle of it,” the singer joked to magazine in 2008.

More seriously, he added: “It’s the closest thing you’re going to get to an Iron Maiden symphony movement.” was the perfect capstone for Iron Maiden’s most adventurous album yet. had all the galloping anthems, lionhearted lyrics and guitar duels with which they had made their name, but it was bolder and grander than anything they’d done before.

Maiden were no strangers to epic, but with , epic got even bigger. was released on September 3, 1984, housed in one of the all-time great metal sleeves. Inspired by the title track’s Egyptian theme, Maiden cover artist Derek Riggs re-imagined the band’s deathless mascot as an ancient Pharaoh, immortalised as a stone statue in front of a huge pyramid with a glowing apex (Riggs also hid Easter Eggs in the painting, including graffitied references to Indiana Jones and an image of Mickey Mouse).

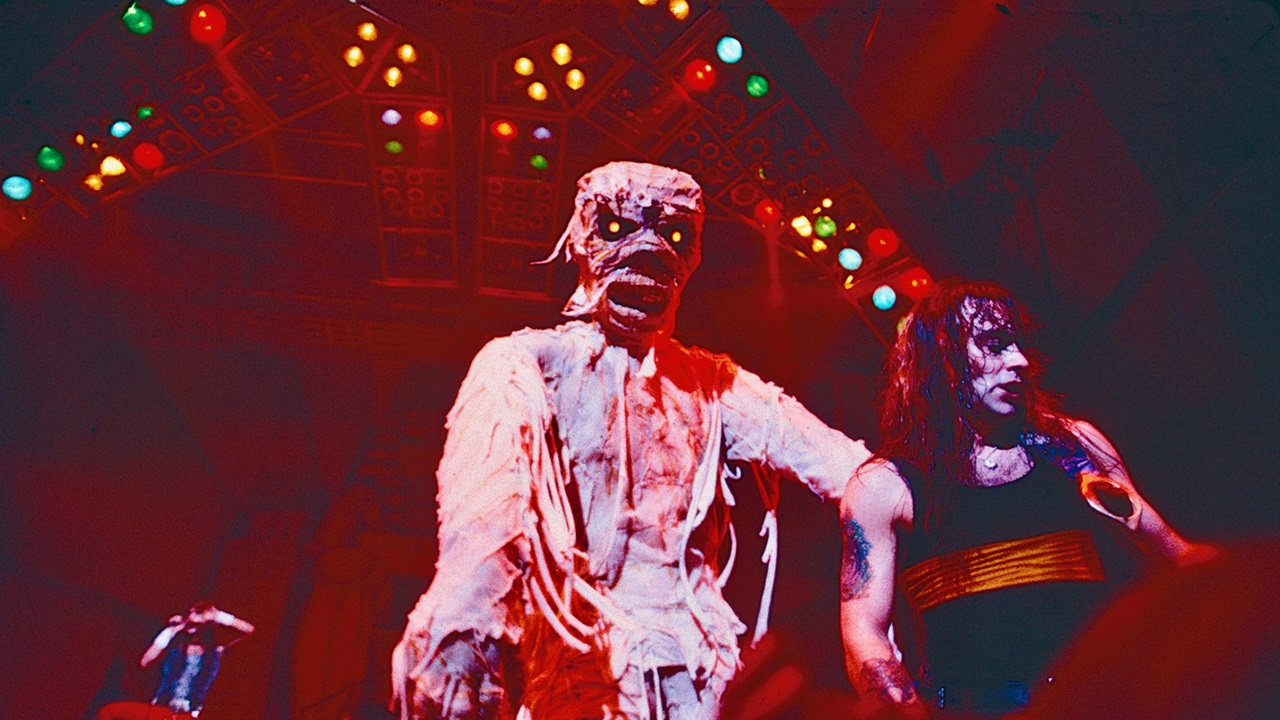

By the time the album came out, the band had already been on the road for a month on the epic World Slavery tour. This was Peak Maiden in live terms. The epic stage set was festooned with vivid backdrops that made the stage look bigger and wider than it actually was, while ramps, pyros, sarcophagi and the bizarre, full-face bird mask Bruce sported during itself – bought from a gay fetish shop in Los Angeles – added to the theatricality of it all.

As always, Eddie stole the show, making an appearance as a lumbering mummy during Powerslave then again as a towering, 30-foot-high bandaged torso erupting from a giant sarcophagus at the back of the stage during itself. The World Slavery tour changed things for Maiden in ways that only become evident in subsequent years. It began with six shows in Poland, making Maiden the first major Western metal band to play behind the Iron Curtain, a feat they repeated in Brazil six months later.

Those appearances turned them into lifelong heroes in both countries, helping to crack open both the Eastern European and South American markets for metal as a whole: where Maiden led, others eventually followed (sadly, rumours that the tour would include in a date in Tibet were laughingly dismissed by Bruce as “a load of bollocks from our PR person...

he thought Bangkok was in Tibet”). But the World Slavery tour also drove the band to breaking point. Even by their standards, it was long and gruelling - 187 shows in 322 days, across 24 countries.

The relentless workload took its toll on them all, but especially Bruce. “ It was the first time I really thought about leaving,” he said in . “I don’t just mean Maiden, I mean quitting music altogether.

I really felt like I was pretty much basket case material by the end of that tour, and I did not want to feel that way. I just thought, ‘Nothing is worth feeling like this for.’” Maybe not, but really did change things for Iron Maiden.

With all its scale and grandeur, it remains a pivot point for Maiden. “It felt sort of like we had got to the top of the mountain with that one,” Maiden bassist Steve Harris said. “We had never really felt that way before.

Everything up to then had been about climbing the mountain. With Powerslave it felt like we were looking out over the rest of the world.” “Some of us were getting sober and cleaning up, others were not.

It’s a recipe for disaster”: The chaotic story of Jane’s Addiction’s Ritual De Lo Habitual, the debauched masterpiece that changed music The 12 best new metal songs you need to hear right now “Jim’s attitude was always: ‘Look out, man, I’m hell-bent on destruction.’ We couldn’t moralise”: How The Doors snatched victory from the jaws of chaos to make the classic Morrison Hotel album Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on and , Associate Editor on magazine and staff writer/tea boy on , not necessarily in that order.

He has written for , the and the totally legendary . He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago..