In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the giant Tower Records on 66th Street and Broadway was as close to a formal meeting place for gay men as a chain store could get. Located on the north border of Lincoln Center and just across the avenue from a Barnes & Noble, Tower was part of a literal cultural intersection. The store, which was usually open until midnight, was at times a vibrant cruising ground for men who liked men who liked opera, dance, music, movies, or theater.

That was particularly true on Tuesdays, when new releases came in and guys could spend a late-evening hour happily perusing the CDs and perusing the perusers. Tower was also, in those years, a place where the terrifying and ever-accelerating speed with which AIDS was ravaging the city’s artistic community was grimly measurable, man by man. You could enter the store hopeful and leave feeling punched in the stomach.

So often back then, the first sign of bad news was the no-news of silence, absence, emptiness — the cheerful publicist who suddenly stopped returning your calls; the seat next to you at the ballet, long occupied by the same passionate subscription holder, that was now unexpectedly vacant. Or the promising actor building an impressive career on Broadway who, without explanation, seemed to retreat from the scene. I was browsing in the store one night in 1991 when I looked across an aisle and saw David Carroll.

A tall, handsome musical-theater star with an embracingly warm tenor voice, Carroll had earned two Tony nominations, the most recent for Grand Hotel in 1990. He had looked healthy at that ceremony; now, a year later, quietly thumbing through the racks of original cast recordings, he appeared drawn, tired, older. He was wrapped in a heavy shawl sweater that hung too loosely.

His cheekbones cast shadows. You had only to see him to understand what was happening. Early in the following year, Carroll collapsed and died at a recording session for the Grand Hotel cast album.

He was 41. The New York Times obituary cited a pulmonary embolism as the cause of his death; it did not mention that he was suffering from complications related to AIDS. This was not atypical; for many years, “cancer,” “pneumonia,” and “a long illness” were used in obituaries, sometimes at the request of families who wanted to avoid any implication of AIDS and, sometimes, of homosexuality.

Carroll’s death was reported by his “companion,” Robert Homma, but Homma was not listed among his survivors at the end of the story. That word was mainly reserved for family members, not for lovers, boyfriends, or (in everything but the letter of the law) husbands. For years in the paper of record, no gay man who died of AIDS-related illnesses was survived by another gay man.

More than 40 years after the start of the epidemic, the full numerical scope of the toll AIDS took on the world of theater in New York remains difficult to assess. It’s not just inaccurate death notices that are the enemy of historical precision; it’s the passage of decades. Many of the partners of those men are now gone, as are many of their relatives; among the living, some still shy away from the stigma attached to AIDS and AIDS-related illnesses.

And, of course, most of those who were taken by the disease died quietly, in apartments or hospitals or hospices, or in the care of the parents or siblings who traveled to New York to pack up their lives and bring them back to their hometowns. Most of those deaths were not recorded in newspapers, but they were not forgotten. Over the years, people in the middle of the crisis started keeping their own lists of the lost — those records were small personal acts of grief and tribute.

Giving the dressers, the hairstylists, the assistant stage managers, the junior choreographers, the chorus boys, the makeup artists, the rehearsal pianists, the accountants, and the pit musicians who died of AIDS their proper place in the narrative of a community that redefined artistic activism at a time of siege and vilification requires collective memory. That itself is a precious and rapidly dwindling resource. The effort to create a definitive list of names — at least as definitive as all of those challenging circumstances allow — began generations ago.

One of the people to try to take it in hand was Peter Neufeld, who started his theater career in the 1960s as the assistant company manager of a mostly forgotten Broadway musical called Illya Darling ; he went on to run a successful theatrical-management company. After almost 30 years in the business, he turned to activism, joining the staff of the philanthropic organization Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS in 1995. One of Neufeld’s first tasks was to reach out to the theater people he’d worked with and create a database of those whom BC/EFA could count on to show up for its benefits, to ask the audience for contributions after shows, to work the phones, or to organize volunteer efforts within Broadway companies.

But he also continued working on a separate, more private document he’d begun more than a decade earlier: a list of everyone in theater (and, as it evolved, in other sectors of the arts) who had died of AIDS-related illnesses. In a desperate time, perhaps it was his attempt to bring order to chaos or to try to turn a crisis that felt infinite and uncontainable into something that was, at least, measurable. An introductory page acknowledges the list’s many sources, from publications ( The Advocate, Entertainment Weekly, Newsweek ) to theater professionals to the Actors’ Fund of America — and, most tellingly, it cites the “particular effort .

.. made by the casts and staffs” of several long-running Broadway shows, including Cats and The Phantom of the Opera.

Those productions were, during these years, essentially permanent ongoing businesses staffed with people who remembered the names of those, both onstage and backstage, who came and went, who were there and then no longer there. As Neufeld gathered and organized names, he strove to include whatever information about the deceased he had at hand, attempting to note the year of their deaths (“James Raitt, 41, Musical Director/Vocal Arranger, Forever Plaid, ’94,” “Bob Brubach, Actor/Dancer, La Cage, ’88”). When he didn’t have details, he simply wrote down whatever he knew: “Son of Joseph Papp, ’91.

” Some entries were apparently just reminders to himself: “Mark.” “Jacques.” When Neufeld (who died of Parkinson’s disease in 2015) retired around 2006, he passed along the list, which had reached an estimated 1,700 names, to Tom Viola, BC/EFA’s then–executive director.

It is, Viola says as he looks over the pages in a conference room of the organization’s midtown offices, an imperfect record: “It was an emotional response, as opposed to a historical response.” What makes the list so poignant and powerful is that it is, ironically, living history, but only as long as there are people for whom it’s more than just a set of professions and ages and dates. “That name right there, Orrin Reiley,” Viola says, underscoring an entry with his finger.

“He was in the cast of You Can’t Take It With You at the Plymouth Theatre with Colleen Dewhurst in 1983.” Dewhurst was, at that point, a venerable stage star with six Tony nominations and two wins, and Reiley was a young journeyman actor who was often hired for the chorus or as an understudy. The role Reiley had opposite her was his final Broadway job; he died a little over a year later at 38.

Dewhurst had liked him and was deeply affected by his loss. She eventually spearheaded the formation of Equity Fights AIDS, one of the two organizations that merged into BC/EFA. “His death was what moved her to activism,” Viola says.

Back in the day at Tower Records, there was a young, highly opinionated gay man who worked the register, an aspiring filmmaker named Kieran Turner. “He was considered the bitchiest clerk ever to work there,” says his friend Christianne Tisdale, an actor who has been part of the Broadway company of Wicked since 2019. “Epically awful.

He knew his stuff, and if you didn’t, he could be fierce. And he was quite beautiful, so, of course, people would’ve been like ..

.” A brief pantomime of gay bedazzlement flickers across her face. “He was a fascinating little creature.

” His first documentary, Jobriath A.D. (2012), was a sad and enthralling portrait of a 1970s performer who was once compared to David Bowie and is believed to be the first fully out glam-rocker; soon after his first two albums, his career went up in flames.

Jobriath died of AIDS-related illness in the Chelsea hotel in 1983, little remembered. By the time Turner started his next film, he was 48, and he had chosen an even more difficult retrieval project — one that, in a way, was intended to finish what Neufeld’s list had begun decades earlier. Titled Ghost Lights: Reclaiming Theater in the Age of AIDS, the film would tell the story of theater’s devastation and resilience in the face of an existential threat to the people who kept it going.

“He felt a huge connection with this population and with this story,” says Tisdale, who came aboard to produce the movie. Turner’s interest had grown from the front-of-house jobs he had taken as a young man working for Broadway’s Shubert Organization. Night after night, it was impossible for him to miss the toll the disease was taking on the theater community.

“Kieran would read obituaries and keep seeing all these deaths in the theater world that were just strange, with all these weird causes,” says Tisdale. “So many young men, but none of them were dying of AIDS. Kieran was like, Oh, there is a story here that’s in danger of being lost forever.

” Years later, he started compiling his own database of names, labeled DEATHS GRID, which became the foundational research for the movie. In 2016, Turner was diagnosed with cancer and had to postpone work to begin chemotherapy. Six years later, as the film was underway, his cancer returned.

Even as he continued to source archival material, he was often in pain that was difficult to ignore or conceal. Nevertheless, Turner came close to finishing Ghost Lights, banking more than 150 interviews with theater directors, choreographers, producers, writers, actors, and journalists, many of whom witnessed the first 15 years of the crisis, before he died at 56 this past December. Turner’s documentary, which is now being overseen by Tisdale and the production company RadicalMedia, is seeking funds for completion.

Tisdale sometimes feels overwhelmed by the breadth of the story it’s telling. “Is a thousand a safe estimate for those who died? It’s probably low,” she says. “Still, that’s the ensemble of Wicked, dying twice a year for 20 years.

All the hopes and dreams they had, all that their families have lost. All the communities that were lost, all the work they had yet to do. It’s all gone.

” At the time of Turner’s death, a handful of interviews remained on his wish list. One of the people he had originally hoped to talk to, the actor Jonathan Groff, initially turned down the request. Groff was still in grade school when the catastrophe unfolded; he told Turner he had more questions than answers.

The producers reapproached him and asked if he would consider serving as, in Tisdale’s words, a kind of on-camera “tour guide ...

a bridge between generations and a conduit to our audience.” He agreed. This is, perhaps, the central mission shared by filmmakers, museum curators, advocates, and activists — to bring a vanished era to life for generations of younger queer people, to tell them what it was like before there’s nobody left who knows firsthand.

It’s something Viola thinks about a lot. Especially in the spring, when young dancers at the peak of their health, promise, and physical strength swarm rehearsal studios for Broadway Bares. Most of them were not born when the annual benefit began 33 years ago.

“How do we reach them?” he wonders. “Do we take them to The Normal Heart ? Do we show them How to Survive a Plague ? We try to give them a sense of what we sprang from.” When he shows those dancers Neufeld’s list, he says they react “the same way we would react to learning about the Vietnam War.

Some with horror. Some with, Oh my God, how could that happen? And some with, Well, that’s interesting, but what does it have to do with me? You hope it’s a warning, but you can’t expect them to absorb that or understand it, not if they didn’t live through it. That is human nature.

” For over a decade, Neufeld’s list sat dormant in the BC/EFA offices. Over time, what had begun as a personal project acquired the weight of a semi-official document — a roll call of the dead. There was only one copy, kept in a file drawer in case it was ever needed.

A few years ago, it finally was. The Museum of Broadway, then preparing for its opening in 2022, got in touch with Viola, seeking his help in choosing names to be part of a permanent exhibition that would commemorate AIDS activism in theater and pay tribute to those who died. Viola retrieved Neufeld’s list, and to supplement it, he turned to his old friend Michael McAssey, a veteran performer and musical director on Broadway and in New York cabaret.

Sometime around 1982, McAssey had opened a pocket-size spiral-bound diary and written LOST FRIENDS at the top of a page. Below, he started jotting down names — of people he’d known, performed with, played for. He searched his memory for the services he had attended and sung at.

The first name he put on his list was Bobby Blume, “a phenomenal piano player and songwriter who needed people to sing his songs on demos. I’d go to his apartment in the West Village and record for him.” When Blume became ill and started missing appointments and rehearsals, most people hadn’t heard the term AIDS.

By the time he died, in 1984, everyone knew it. McAssey kept writing — there was Greg and John and Scott and John and Tom and Richard and Tory and John and Eddie and Timothy. He added around 125 names over the next five years.

Most, but not all, of the lost friends were victims of AIDS. Every December on World AIDS Day, he posts the names on social media. “People are always saying, ‘Well, that’s morbid,’” McAssey says.

“It’s not morbid. I look at those names and they make me smile. The people I would hang out with at the cabarets and the piano bars in the early days became a sort of second family.

We would have Thanksgivings together — the people who couldn’t go home. These were people I laughed with. We had the best times before the horrifying times.

” Even after eliminating dozens of names, McAssey and Viola still had well over 1,000 names to offer the museum — more than could fit on the exhibition’s memory wall. McAssey has since spent hours there, looking at the finished exhibit; sometimes he’ll photograph a name on the wall and send the picture to a family member as a way of letting them know that a loved one has not been forgotten. And he still thinks about the people whose names aren’t there.

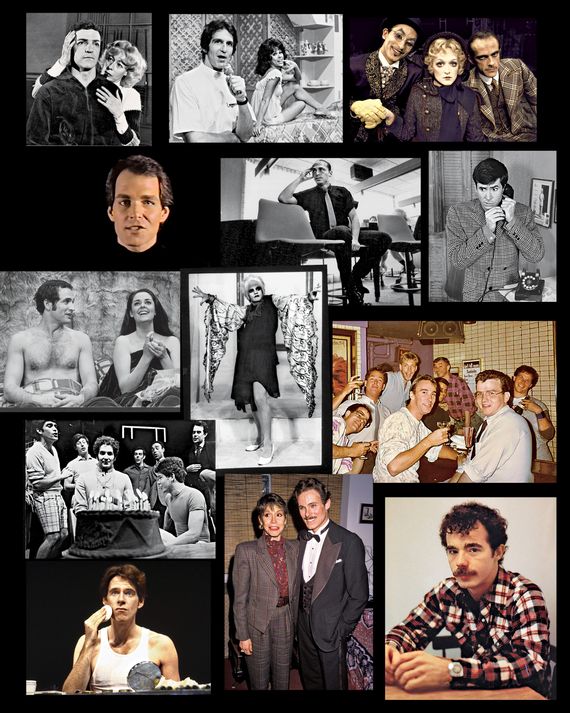

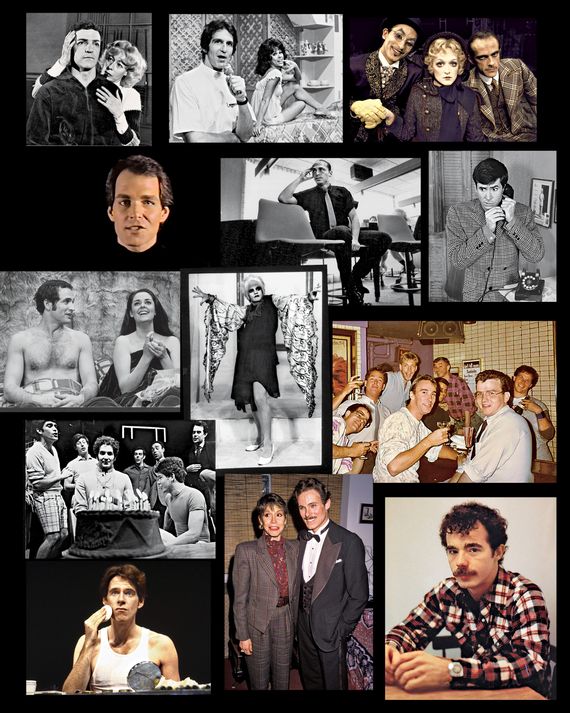

“I don’t know how many times I’ve stared at that thing,” he says. “Ultimately, you just have to let it go.” Photo-collage: From left, top row: Robert Drivas (d.

1986) and Eileen Heckart in rehearsal for And Things That Go Bump in the Night in 1965. Leonard Frey (d. 1988) and Rita Moreno in The National Health in 1974.

Tony Azito (d. 1995), Meryl Streep, and Christopher Lloyd in Happy End in 1977. Second row: Orrin Reiley (d.

1984) in Seein’ the Light in 1978.Ron Vawter (d. 1994) at the Adelaide Festival Theatre in 1986.

Anthony Perkins (d. 1992) in Harold in 1962. Third row: Larry Kert (d.

1991) and Susan Browning in Company in 1970. Charles Ludlam (d. 1987).

Staff of Don’t Tell Mama in 1982. Three died of AIDS-related illnesses. Cast of The Boys in the Band in 1968.

Five of the original cast members died of AIDS-related illnesses. Bottom row: Peter Evans (d. 1989) in A Life in the Theatre in 1977.

David Carroll (d. 1992) and Mary Tyler Moore backstage at Grand Hotel in 1990. Bobby Blume (d.

1984). Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism . If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the April 7, 2025, issue of New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the April 7, 2025, issue of New York Magazine. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Notice and to receive email correspondence from us.

.

Entertainment

The List Keepers

The AIDS crisis shattered Broadway, and the scope of the loss has never been fully accounted for. Some kept their own records.