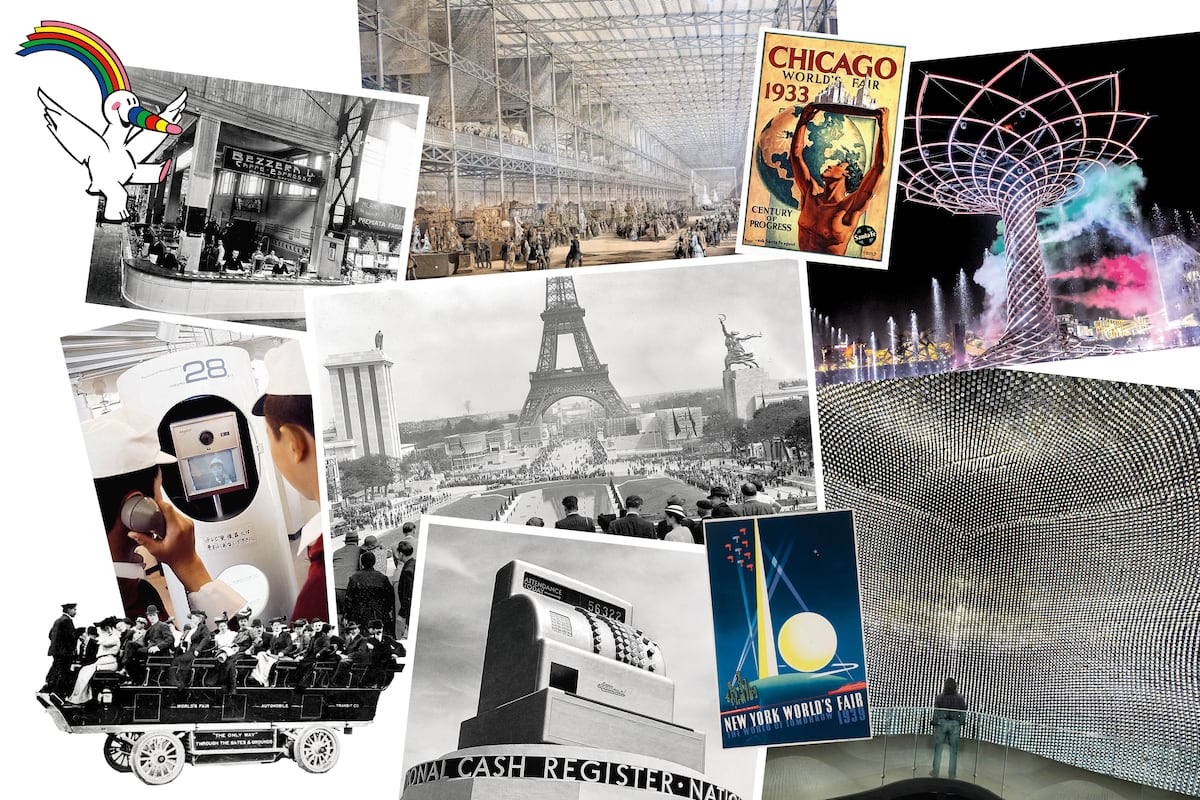

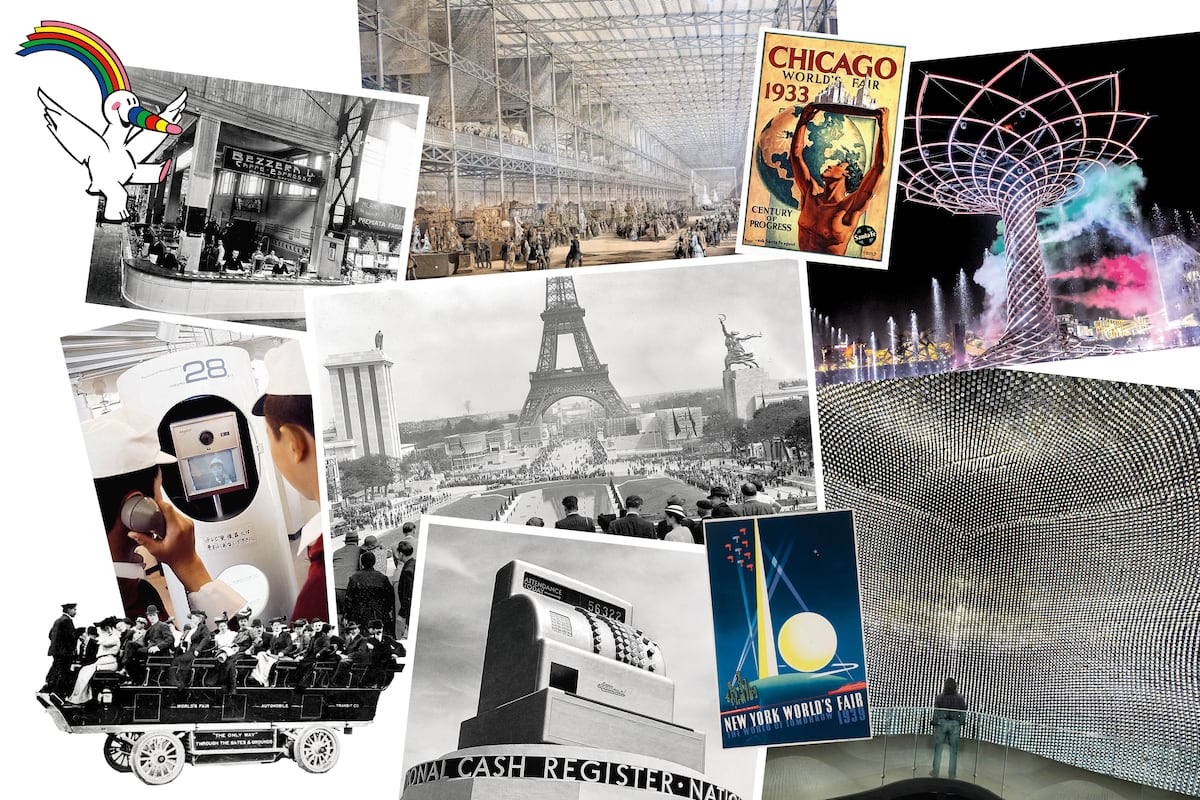

The event that heralded a globalized world in the 19th century (and is still going strong) World’s Fairs were created to launch futuristic technology and products, but ended up selling ideas and experiences. 174 years after the first event, Osaka expects 28 million visitors from April 13 to October 13 Since their inception 174 years ago, World’s Fairs — direct descendants of traveling trade fairs — have sought to dazzle visitors with technological innovations, colossal structures and the allure of the ephemeral. Until the emergence of television and the internet, they were the perfect stage for presenting innovative products and distant worlds to the general public.

Despite the disappearance of their original, practical purpose — which was on display in London in the 19th century, at the Great Exhibition of the Products of the Industry of All Nations — these Expos continue to attract millions of people every five years. But why is this the case? Well, a decisive factor is their ability to adapt to social needs and reflect the global interests of the moment, from technological wonders to sustainability. At the first London-based event, held in 1851, a device capable of transmitting images using electricity was demonstrated.

The “picture telegraph” was a precursor to the fax machine, which took more than a century to become an indispensable device in every office (before being replaced by email). The British fair, which combined innovation and magnificence, brought together exhibitors from 25 countries in an iron-and-glass enclosure, resembling an imposing one-million-square-foot greenhouse (the equivalent of about 12 football fields). Built in central Hyde Park, it lasted six months and attracted more than six million visitors.

.. more than double the population of the English capital at the time.

The Osaka World Expo — taking place from April 13 to October 13 — will host a magnificent circular observatory in the Japanese city, 2,214 feet in diameter and 66 feet high. It has already been registered in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s largest wooden architectural structure. It will bring together 165 countries and various international organizations.

Beyond displaying technological inventions, the pavilions will present ideas and concepts that are in tune with the times and current concerns. The organizers expect 28 million visitors. The circular structure, designed by Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto, is intended to be a symbol of the unity of the participating countries, based on a contemporary interpretation of traditional Japanese wooden construction.

It will literally embrace the three exhibition areas with its pavilions. This is how its creator summed up the project and the convention in an interview with the architecture magazine Dezeen : “Of course, it [cannot] solve all the problems of the global situation, but I think it is very precious that so many countries can gather together to have a [conversation] and create a wonderful [sense of] unity.” Colossal scale has been a constant feature of the sensorial experience offered by World Expos.

In Osaka, Gundam will be present: a 49-ton, 56-foot-tall robot from the anime universe. Resting on its left knee, its right hand extends toward the sky, symbolizing the construction of a new era. Many of the architectural works at these events are ephemeral, while others remain long after.

Some even become icons that identify their cities, such as the Atomium in Brussels (from the 1958 Expo), or the Space Needle in Seattle (1962). The most famous example is surely the Eiffel Tower , built for the 1889 Paris Expo. Spain also boasts notable examples, such as the German pavilion at the 1929 Barcelona World’s Fair.

Designed by Mies van der Rohe, it was dismantled at the end of the exhibition...

but its significance in the history of architecture was such that it was rebuilt in the 1980s. Two works by Lluís Domènech i Montaner from the same fair remain: the Spanish pavilion and the National Palace. And, in Seville, we find the Schindler Tower, built on the island of La Cartuja for the 1992 World’s Fair.

The permanence of the Expos’ architectural legacy is an oft-cited argument against the possibility that these events could, one day, be replaced by virtual reality versions, or immersive online experiences. “Nothing replaces the face-to-face experience. Our brains are wired to connect,” Charles Pappas explains.

He’s a historian and the author of Flying Cars, Zombie Dogs, and Robot Overlords: How World’s Fairs and Trade Expos Changed the World (2017). “If you want to convince a large audience of an idea — which is the essence of an Expo — the most effective way to do it is live,” he continues, emphasizing the revalidation of in-person experiences, such as live concerts or festivals. “Would Woodstock or a carnival exist if they were only virtual? They would be no more memorable than a dream,” the expert asserts.

For Dimitri S. Kerkentzes, secretary general of the International Exhibition Bureau (BIE), the human need for in-person experiences was confirmed by the 24 million visitors to the 2020 Dubai Expo (which was postponed to 2021-2022, due to the Covid-19 pandemic). “It proved that, even in the most difficult times, people find ways to come together,” he emphasized, in a video call with EL PAÍS.

He asserted that the emirate’s World Expo could have been the last World Expo if digitalization had replaced it. “But that didn’t happen. Technology doesn’t eliminate the need for exhibitions.

Rather, it enhances the physical experience of them,” says the director of the BIE, an intergovernmental organization established in 1928. The BIE established the universal (or world) category for events that take place every five years. Countries from all over the world participate with their own pavilions, where, for six months, they showcase their cultural, scientific and technological advances.

During the intervals between these fairs, other thematic events — focused on specific topics, such as transportation, water, or energy — take place for shorter periods (three months) and do not require official pavilions. “When a country decides to bid to host one of these events, the first thing they consider is the legacy — both tangible and intangible — that it will leave behind,” Kerkentzes explains. “The benefit to citizens is one of the most important aspects,” he adds, citing Lisbon as an example after its 1998 Specialized Expo with the theme “The Oceans, a Heritage for the Future.

” Following the Seville ‘92 model — whose urban regeneration strategy and integration of exhibition venues into city life demonstrated the power of Expos to transform a city — the Portuguese capital reintegrated disused port areas and extended the urban fabric toward the riverfront. Pappas often begins his lectures with long lists of inventions that transformed some aspect of our lives after being launched or popularized at World’s Fairs, such as the hamburger (which became widespread after its 1904 introduction in St. Louis), or nylon stockings (introduced at the New York World’s Fair in 1939).

He recalls that Europe and the United States monopolized these events until the end of the 20th century. “The West has been a kind of Sun around which World’s Fairs orbited,” he maintains. Of the 37 World’s Fairs registered and assigned by the BIE through 2030, France, the United States, and Belgium have organized almost 45%.

To explain the shift toward the East that these events have taken this century, the historian highlights the fact that Dubai became the first city in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia (MEASA) region to host a World’s Fair. “It wasn’t just a $20 billion party; it was the official presentation of that emirate to the world. Or perhaps ‘coronation’ would be a more appropriate term,” he notes.

In the 21st century, Asia and the Middle East have ceased to be mere participants and have become hosts and protagonists, with notable events such as the Aichi Expo (2005), in Japan; Shanghai (2010), in China; and Dubai (2020), in the UAE. And, after Osaka, Riyadh — the capital and largest city of Saudi Arabia — will host the 2030 World Expo . “Wherever there’s emerging wealth, there are World Expos,” Pappas adds.

Until the mid-20th century, these exhibitions also served to promote agendas of cultural superiority, with recreations of life in distant lands labeled as “ethnographic spectacles.” Indigenous peoples from several countries were even brought to the Paris Exposition that saw the birth of the Eiffel Tower, including 11 Selk’nam people , who had been kidnapped in Tierra del Fuego by a Belgian slave trader. World Expos have also been decisive platforms for artistic movements, such as Japonisme, inspired by the Japanese ukiyo-e prints that many Europeans first encountered at the 1867 Paris Exposition.

The impact it had on European artists of the time was decisive in Impressionist painting and in styles such as Modernism and Art Deco. Great names in Spanish culture were linked to the history of world expositions. For instance, thanks to a showcase designed by Antoni Gaudí — which was exhibited at the Spanish Pavilion in Paris, in 1878 — the recently-graduated architect caught the attention of Eusebi Güell, his future patron.

The international acclaim of Picasso’s Guernica is partly attributed to its inaugural exhibition in the Pavillion of the Spanish Republic at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair, which opened a month after the air raid on the Basque town by the Condor Legion . Meanwhile, Salvador Dalí’s remarkable ability to combine the disconcerting and the popular in art made him the Spanish painter who best exploited the World’s Fair format. His Dream of Venus — a controversial pavilion with erotic content, designed for the 1939 New York World’s Fair — is considered a landmark for its pioneering use of multimedia content.

Even though World Expos maintain a high degree of technological optimism, in the 21st century — marked by climate change, the energy crisis and biodiversity loss — ecological responsibility has come to redefine their discourse. “How can technology and nature coexist? How can we help one another, without destroying the planet in a process of incessant growth?” are questions posed by the secretary general of the BIE to explain the mottos of recent exhibitions. In Osaka, the theme will be “Designing the Future Society for Our Lives.

” And the pavilions — many of them built with wood and other recyclable or recycled materials — present ecological proposals that are aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Under the Shinto concept of circulation ( junkan , in Japanese), Japan’s pavilion will house a large recycling plant. This is meant to be taken as an exhortation to live more sustainably and in harmony with nature, avoiding waste and valuing the cycles that make our existence possible.

The Spanish pavilion — which will be an architectural representation of the Sun reflected on the sea — will have sections dedicated to the blue economy and biosphere reserves. Its central theme will be the Kuroshio Current: the movement of water that the Basque explorer and friar Andrés de Urdaneta used to navigate from Asia to the Americas in 1565. It was also used by the Manila galleons — trading ships that linked Spain to the Philippines — as a cross-continental trade route for two-and-a-half centuries.

As global venues where nations and businesses converge, World’s Fairs are also platforms for soft power , public diplomacy and, occasionally, a stage for territorial claims or ideological propaganda. Without naming names, Kerkentzes recounts how, at the start of an exhibition, he received a call from a participating nation complaining that the map displayed in the pavilion of a country bordering theirs included disputed islands. “I called them and made them understand that the problem would not be resolved during the event,” he explains, emphasizing the role of exhibitions as a neutral meeting ground.

The most public ideological clash took place when the pavilions of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union — located opposite each other at the 1937 Paris Expo, with the Eiffel Tower in the background — competed over the height of their respective emblems: the imperial eagle with the swastika in its talons, versus a worker and a peasant woman carrying the hammer and sickle. “That episode [was important] and is one of the reasons why exhibitions have evolved, becoming spaces for dialogue and cooperation,” Kerkentzes notes. This year, the notable absences will be Mexico and Argentina.

And, back in November of 2023, Russia — citing “insufficient communication” with the organizers in Osaka — canceled its pavilion. Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo ¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción? Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro. ¿Por qué estás viendo esto? Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS. ¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí. Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.

Osaka Lluís Domènech i Montaner Sou Fujimoto Barcelona Sevilla Antoni Gaudí Paris Pablo Picasso Salvador Dalí Mexico Argentina Why has a social network where everyone is a bot become so popular? Aline Sousa, the Brazilian recycler who put the presidential sash on Lula: ‘Recycling has a race and a gender’ No crash, but certainly not skyrocketing: Bitcoin stagnates in the face of tariff uncertainty Trump 2.0 stock market lessons: The cost of trying to ride the wave of volatility Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo, founder of the Guadalajara Cartel, released at 95 The Spanish victims of the New York helicopter crash: Two Siemens executives and their young children Ukraine accelerates weapons production: ‘We produce more howitzers than all of Europe combined’ The lives lost in the Dominican Republic nightclub tragedy: A governor, a merengue singer and a former MLB player The honeymoon is over for Donald Trump.

Top

The event that heralded a globalized world in the 19th century (and is still going strong)

World’s Fairs were created to launch futuristic technology and products, but ended up selling ideas and experiences. 174 years after the first event, Osaka expects 28 million visitors from April 13 to October 13