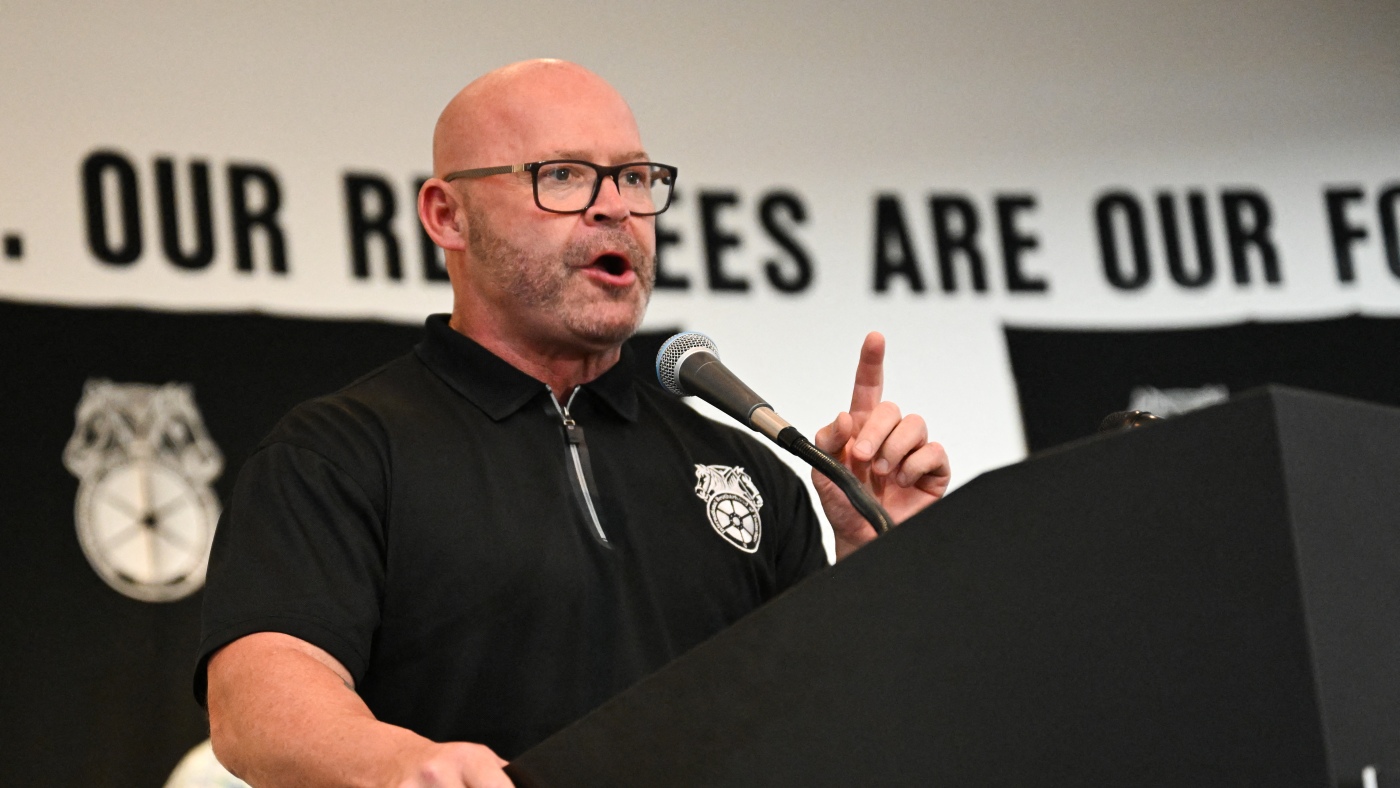

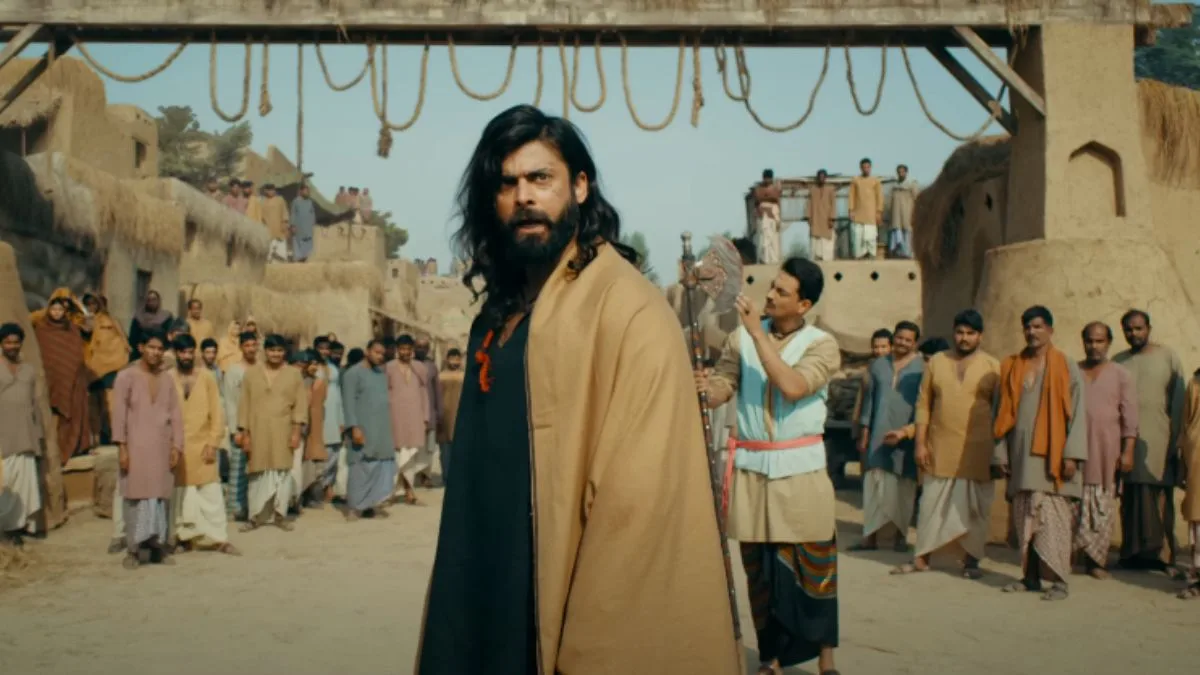

By now, boxing movies are such an overplayed genre, it’s tough for any filmmaker to innovate how the sport appears on screen. Sean Ellis ‘ “ The Cut ” finds a way around that problem by focusing on physical and psychological struggles outside the ring, especially the grueling battle to make weight. The film tries several things at once, including a flashback structure than doesn’t fully connect, but its impact ultimately comes down to Orlando Bloom ‘s visceral, transformative performance as an unnamed Irish brawler.

Bloom’s protagonist — referred to as “the Boxer” in press notes, and frustratingly, nothing at all in the movie — can be seen engaged in a professional boxing bout exactly once in “The Cut.” During the film’s brief prologue, the accomplished prizefighter seems well on his way to another victory, when something mysterious and unseen distracts him from off-screen — something in the ether that only he can see — resulting in his opponent getting the upper hand and opening a deep, career-threatening gash above his eye. A decade later, the Boxer diligently runs a dilapidated gym in Ireland with his wife Caitlin (Caitríona Balfe), and can be seen at one point forcing himself to throw up.

His life may have changed, but his past seems to live with him, an idea Bloom embodies completely in every moment, and unveils further when his character has a chance to get back in the ring for one big Vegas prize fight — on one confounding condition. Since he’d be replacing a previous fighter, who died of dehydration during his training, the Boxer has to lose 30 pounds in a single week (more than most people could hope to in several months) in order to make the weight class. Cinematic transformations touted as “Oscar worthy” can often come down to bodily changes — there’s plenty of that to be found here, much of it on screen — or even drastic hair and makeup decisions.

Both of these certainly contribute to Bloom’s metamorphosis, as his cauliflower ear and the nicks in his buzz-cut hair and above his eyebrow tell their own story about the punishment he’s taken. However, what separates Bloom’s performance from the pack is the way he carries himself. The Boxer is always rankled and always on guard, with eyes that seem to dart and search for opportunity.

He has a suppressed hunger within him, and tight facial muscles that speak to a rough upbringing. When he moves, and even when he talks, he does so as though he’s weighed down, and he has to snarl just to get words out on occasion. It would seem cartoonish, like an impression of Connor McGregor, if Bloom weren’t so thoroughly lifelike in his motions, as though he had not just imagined a different past for himself in order to reach this place, but somehow actually lived it.

At first, when Caitlin takes on the role of lead trainer and the couple chooses their own crew, “The Cut” takes an almost self-reflexive approach to boxing cinema, literalizing the battle between family and obsession by mixing the two together. In the parlance of the “Rocky” films, Adrian and Mickey are one and the same, leading to more of an internal conflict for Caitlin (and a more active one) than a sports-movie wife on the sidelines. However, the complications increase tenfold when, unable to lose the pounds despite pushing his body to the brink, the Boxer decides to bring a new trainer into the fold, Boz (John Turturro), a condescending and practically demonic entity, who gets results because, in his words, he doesn’t love anyone or anything except winning.

Through torturous workout scenes, and shots of scant, flavorless scraps (just enough to survive), “The Cut” all but turns the typical training montage into its own nightmarish film, with a disconcerting helping of a quiet male eating disorder on the side. All the while, Ellis also keeps flashing back to the Boxer’s childhood in Troubles-torn Ireland through black-and-white snippets. These attempt to flesh out the neuroses behind the Boxer’s state of mind, but Bloom already embodies this character so thoroughly (and so freakishly) that these scenes become perfunctory — a feeling that’s only magnified when they start robbing the training scenes of tension whenever they appear.

The Boxer’s origin story, as it were, has lurid dimensions that make his recurring anxieties click into place, but explaining them takes forever. “The Cut” would have likely been better off had it remained laser-focused on its hellish physical ordeal. The psychology of tragic dimensions can already be gleaned in poetic ways, rather than needing literal details (which unfortunately go hand in hand with the movie’s thuddingly literal hip-hop soundtrack, with tracks that explain the events on screen).

Ellis, who doubles as his own cinematographer, even employs delightfully subjective horror imagery to enhance the Boxer’s story of drive and physical punishment — “The Cut” is the rare boxing movie that lacks a single moment of in-ring allure or competitive glory — which is dour enough, and doesn’t require constantly cutting away. That the Boxer is closed off from his pain ought to be sufficient explanation for the film’s look at the toxicity of sport, because Bloom’s gut-wrenching performances makes it enough. While there’s a more streamlined and thus more effective version of “The Cut” in there somewhere, what remains on screen is plenty harrowing as it is, and allows Bloom to finally cement himself as a truly great performer — not for the lengths he’s willing to go, but for the spellbinding end result.

.