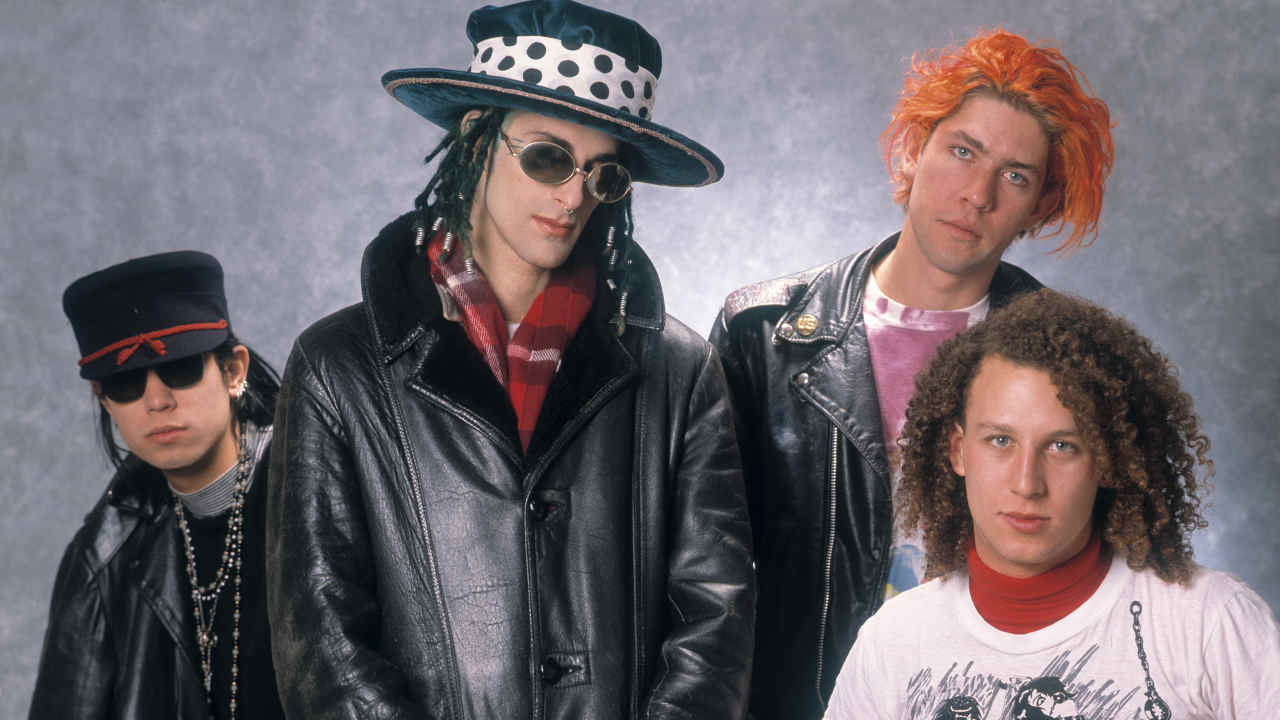

Hailed by none other than Axl Rose as ‘the best talent in LA’ back in 1987, Jane’s Addiction started in 1985 by vocalist Perry Farrell and bassist Eric Avery, and were named after a housemate of the singer – Jane Bainter – who was a drug addict. By 1986, they’d completed the line-up with guitarist and drummer Stephens Perkins, and had agreed a deal with Warner Bros, but released a self-titled live album on the independent Triple X label. This was recorded at the famed Roxy club in LA, and put out in January 1987.

In August of the next year, the band released their debut studio album, the celebrated album, which took art rock and shoved a needle straight into its arse. It had a totally depraved sense of purity, and sent Jane’s Addiction spiralling towards success, as it nearly cracked the Top 100 in America. But it was to be their next album, , that would take things even further.

That record, equally blissful kaleidoscopic and dark, became a huge success, selling a million copies and giving the alternative rock scene a foot in the mainstream. But the band that made was anything but blissful. The success of had exacerbated existing tensions between four already disparate and strong-willed characters.

“Success has a habit of inflating egos and making everyone feel that they need to fight for the recognition they claim is their right,” explains the vocalist. “All of our egos had been raised after . What made it worse was that some of us were getting sober and cleaning up, while others were not.

Add in the fact that we were all exhausted from spending 18 months on the road, which made our tempers even more fragile, and it’s a recipe for disaster.” In order to make a potentially fractious situation run more smoothly, the band re-enlisted Dave Jerden, who had co-produced with Perry. Jerden could act as a bridge between the warring factions within the band.

“We worked with Dave on , and kept him for ,” says Perry. ‘We knew and understood him, and felt comfortable with the way he worked. So, I could leave him to get on with recording the rest of the guys, knowing that he’d do a great job.

So, despite all our problems, we ended up with a great-sounding album. Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox! By the time Jane’s Addiction went into Eldorado Studios in Los Angeles, they had all but one of the songs written and were ready to roll. “I don’t see what you gain by writing in the studio,” says Perry.

“It’s wasteful on all levels. We actually had two songs – and – written before we finished . But we all felt that they were far too sophisticated for that album, and should be saved for the next one.

When we wrote the material for , we were influenced by Flipper, The Stooges, James Brown and Joy Division. The songs came easily, and they fitted a pattern. But our new stuff was on another level altogether.

It was almost like classical music to me. “Our aim had always been to continually develop and expand our horizons,” he continues. “To do a series of albums like would have been boring and counter-productive to us.

But we didn’t want to move too fast. But we knew when we finished the record that we already had songs prepared that would blow away anything on the album. The ‘difficult second record’ wasn’t going to be a problem.

” Except the one song that was brought to the table late in the day, the hypnotic , did cause problems. “There were objections from some in the band to the song, because it was a last-minute thing," recalls Perry. “I had to fight to get it through, and onto the album.

” The album’s euphoric opening track, , began with a slyly provocative spoken-word intro, as a sultry female voice intones in Spanish: ‘We have more influence over your children than you do, but we love them’. “That’s from a poem of mine, which was about the fact that at the time young people – and I include myself in this – were a nightmare for parents,” says Perry. “We were out of control and wouldn’t be stopped.

It was a case of the insane running the asylum. Having that sort of female voice – which was provided by a friend of mine, Cindy, who was like a Latino Marilyn Monroe – made a huge impact.” Another song would be crucial in giving the band a mainstream breakthrough: the kleptomaniac’s anthem , with its dog-bark opening.

“It is a true story, like all of my songs. I used to love going into shops and staring at the freaky things, like a hologram of a cat’s head that stares at you, and as you change position it turns into a skull. But I had so little money back then that if I wanted it, then I’d have to steal it – simple.

I did a lot of that. We were so broke that we all lived in an apartment and used one motorbike to get to the studio – even when we were doing .” But the centrepiece of the album is the suite of linked songs inspired by the drug-related death of Perry’s girlfriend Xiola Blue (the ecstatic, 10-minute , the aforementioned ) and the suicide of the singer’s mother when he was a young child (the gentle ).

“When my girlfriend died, it actually made it easier for me to write about my mother,” he explains. “I’ve never said this before, but if you go to on , the line ..

.that’s about my mother. Her maiden name was Smith.

My mum died in different circumstances to my girlfriend, but the two became connected in my mind. They were both lost souls, who ran out of reasons to live, and therefore had no choice. “I deal with these sorts of tragedies perhaps a little differently to many others,” the frontman continues.

“I don’t dwell on them, cry or ask for sympathy. They happen, and you move on. I will never allow them to take over my life and define who I am.

These things never had me rushing into therapy – what a waste of time that is! I object to organisations like Narcotics Anonymous or Alcoholics Anonymous, because they never allow people to move on. You spend your life marching on the same spot. So, I wrote about the two deaths which affected me, and then got on with what I wanted to do.

My advice is always strive forward for a good life, for glory.” But the brilliance of the songs Jane’s Addiction had written were in inverse proportion to the tension of making the album. “There are those who’ll tell you that antagonism between bandmates is good for creativity,” says Perry.

“That is definitely not the case. Most bands write and record their best songs when there’s harmony in the camp. Friction just makes everything so difficult.

Things got very bad between Dave and myself. At first, I was in the studio when he was recording his parts, to see if I could help. But he accused me of trying to overwhelm and suffocate him, so I ended up just coming in for my vocals, and leaving the others to get on with their jobs.

” Despite those tensions, the album was finally finished and released in August 1990. It reached number 19 in the US charts and number 37 in the UK. This was despite, or maybe because of, controversy over the cover.

Having caused outrage with the artwork for , Perry did it again with his sexual and religious symbolism on the new album. The sculpture – by the frontman – of three intertwined, almost naked bodies, set against a backdrop of African spiritualism, led to protests and demands for a cleaner cover to be created. Just one more example of the way that Jane’s Addiction were prepared to be confrontational.

“This was typical of a society who seek to control,” says Perry of the cover. “But we never looked at this as a compromise. It focused attention on the original.

” But any sense of triumph was shortlived. The fractures within the band had widened beyond the point of repair. In 1991, Perry conceived the travelling festival-come-circus Lollapalooza, which saw Jane’s a topping bill featuring a diverse array of bands that included Siouxise And The Banshees, Nine Inch Nails and Rollins Band.

But it would also be Jane’s Addiction’s farewell tour – they would split after the tour’s end. “Personal problems and backstabbing did us in,” explains Perry simpy. After the final date of Lollapalooza, in August 1991, Jane’s Split.

Perry and drummer Stephen Perkins continued to play together in Porno For Pyros, while Dave Navarro briefly joined the Red Hot Chili Peppers. But despite their differences, the bond that joined the band members never truly broke: they’ve reunited and split multiple times. But for all the drama that surrounds it, remains an iconic album – the doorway not just to the 1990s, but the point at which culture itself started to shift.

This record, with its themes of sex and death, drugs and self-destruction, stands as a weirdly uplifting reminder of a time when the boundaries were there to be erased. “People have told me that is so gloomy, but at the time I couldn’t see this,” recalls Perry Farrell. “But if I look back, then yes it had a very dark atmosphere.

But to me, darkness is beautiful, and I have always embraced the darkness. What I was doing was writing about my life. It was never meant to be deliberately cathartic.

These were my experiences.” “I enjoy the fact that we could talk about such dark matters as appeared on the album, and then celebrate going out and stealing, or having sex. To me, these are interchangeable.

If you want to suggest that I was being cathartic at some points, then OK. But then, I could also get very physical with my lyrics and the music. Overall, I believe the album has stood up over time, because it’s about having fun whatever you do, wherever you are in life.

To me, is an authentic and truthful record.” The 12 best new metal songs you need to hear right now “They may be calling it a day, but these masters will always have a devout tribe”: Armed with 40 years of anthems and some stellar support acts, Sepultura’s final UK show is an unmitigated triumph “The most exciting thing was, even though John was no longer on this planet, here he was in the studio with us”: Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and Jeff Lynne on how The Beatles made Free As A Bird Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for magazine in the late 70s and in the early 80s before joining at its launch in 1981. His first book, , published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year.

Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the song in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. .

.