Three sisters who call Fort Providence, N.W.T.

, home are on a journey of reunion. The sisters are survivors of the Sixties Scoop, a government practice in Canada from the 1960s to 1980s of removing Indigenous children from their homes and placing them in foster care or putting them up for adoption. The sisters grew up in separate parts of the country and didn't know about each other until their adult years.

Delphine Gargan, Sariah Stanley and RavenSong Gargan, now in their late 50s, met as a group for the first time on Aug. 30 to travel together from Edmonton to their home community – where their mother grew up and where Delphine was born – to reconnect with family, the land and their pasts. For RavenSong, it's a chance to experience a piece of what was stolen from her.

"We hopped in the truck and we went looking for buffalo this morning and we said if we had grown up here we would have done that together as teenagers," she said. "We're doing some of the things we've never done. Jumping on beds and things like that.

" RavenSong said there is something different about being on her own land. The noise and vibrations she feels in the city stop when she comes home to Fort Providence. The Mackenzie River in Fort Providence.

For RavenSong, the vibrations she feels in the city stops when she's on her own land. (Natalie Pressman/CBC) RavenSong, now living in Richmond, B.C.

, is the founder of a non-profit called the Sixty Scoop Indigenous Society of B.C. It focuses on reintroducing survivors to ceremony and tradition as a form of healing.

The society secured funding from the 60's Scoop Healing Foundation to pay for travel expenses to bring survivors home. That's something RavenSong says the society hopes to do more of, and her board of directors decided that as president, she should have the experience of going home before she helps other survivors do the same. "I couldn't do it if my sisters weren't willing," she said.

"It hasn't been easy for any of us to make commitments to anyone because of who we are and to make a commitment to do something this big with not knowing each other, that was a big thing. It was scary." Putting the puzzle back together Sariah, the middle sister, said she's now in a place in her life where she can explore her past.

Sariah has been sober for five years and is living in Drayton Valley, Alta., working as an industrial medic. She first learned about her sisters in 2004.

She was living in Windsor, Ont., at the time and got a call from RavenSong introducing herself and telling her about their other sister Delphine. It turned out Delphine was living just six blocks away.

"It was surreal," she said. But life got in the way, Sariah moved for work, and she lost touch with her sisters. This time, she said, keeping in touch with her sisters will be for real.

"And it will come from a genuine place because of where I am in my life. I'm balanced and I'm settled and I think I'm in a good spot to be able to just keep in touch," she said. While in Fort Providence, the sisters put on a feast of salmon, rice and bannock for community members to come by and meet them.

While in Fort Providence the sisters put on a community feast of salmon, rice and bannock. They said it was fun to cook together and work as a team. (Submitted by Lew Jobs) Delphine, the eldest sister, described relatives coming into the seniors centre and hugging them and telling the sisters they love them.

"I think a lot of them were overjoyed, number one that we're still alive," Delphine said. Delphine, now a cook and paramedic living in Revelstoke, B.C.

, said it's been amazing to spend time with her sisters, but she's also mourning the life that was taken from her. "A sense of loss, of culture and family and community, and we come here trying to get some of that back, trying to regain some of that back," she said. "It's kind of reopening up the trauma of being a part of the Sixties Scoop where you felt unloved, unwanted.

Who am I? Where's my identity? We're trying to put the puzzles back together as best we can so we can continue healing." What they didn't expect Before leaving the hamlet, the sisters visited the cemetery. They wanted to pay their respects to relatives buried there.

What they found was their late mother. She died in Victoria, B.C.

, they said, and they didn't know she would be buried in the N.W.T.

community. Marie Alice Gargan is the mother of Delphine, Sariah and RavenSong. Her headstone is in the cemetery in Fort Providence.

(Natalie Pressman/CBC) Sariah said she's happy her mother is home. "She is where she needs to be and hopefully she can find some peace," she said. But for RavenSong, she sees it as a betrayal.

"They knew that she had three daughters and they chose to do a burial or a memorial day for my mom and never told any of us," she said. "We want to be part of these things. These things are important.

Unbeknownst to [Fort Providence's community members], they've been in my heart and in my thoughts every day for 57-and-a-half-years." Though some living in the hamlet have wanted to meet the sisters and share stories about their mother, not everyone in the community has provided the warm welcome they hoped for. "I think the reconnection is between us three here.

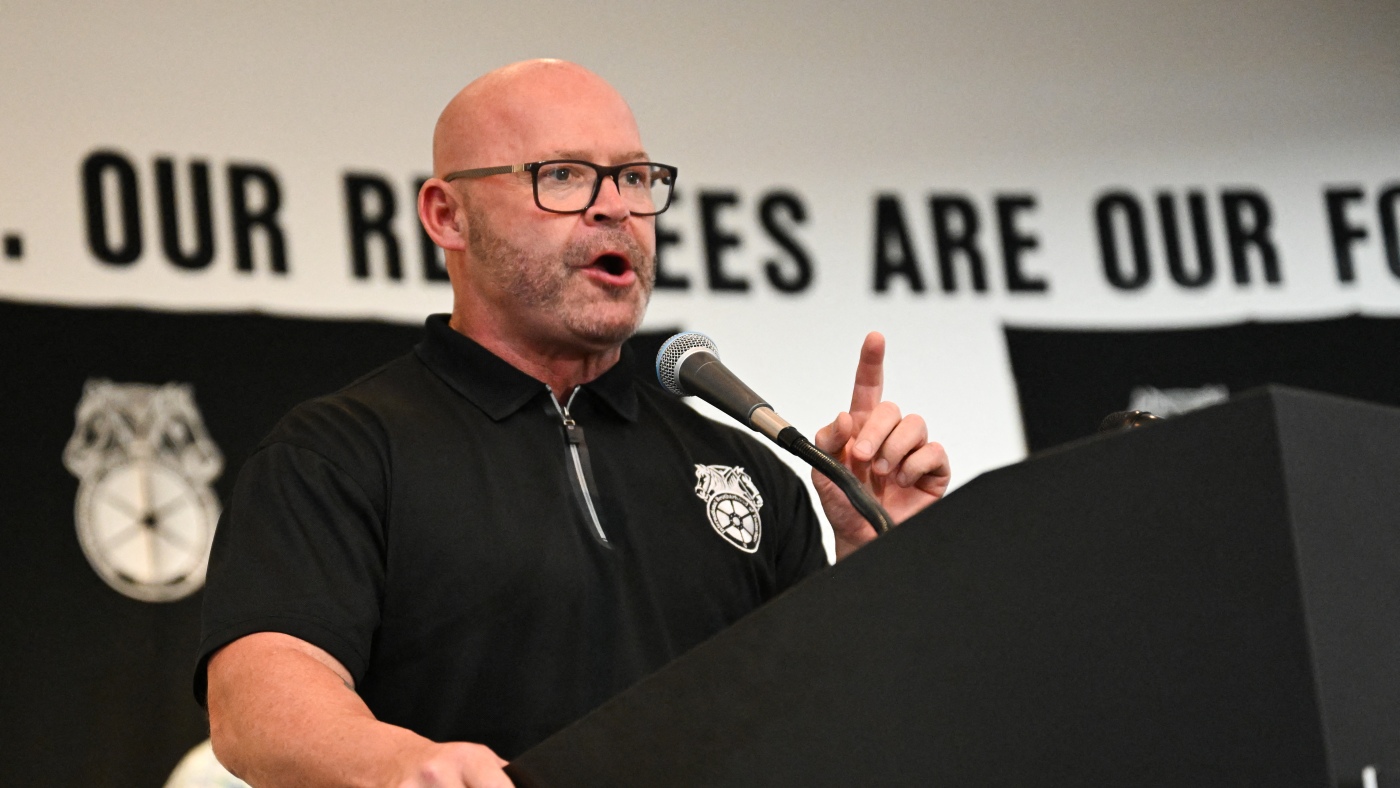

As far as reconnection within the community, even though we're from here, we weren't raised here so we're strangers," Sariah said. "We're strangers and we're treated as such." Lew Jobs, a contractor with the Sixty Scoop Indigenous Society of B.

C., travelled north with the three women. He's also a Sixties Scoop survivor originally from Tuktoyaktuk, N.

W.T., and has had his own experiences returning home.

Lew Jobs works with the Sixty Scoop Indigenous Society of B.C., and he travelled north with the sisters.

A Sixties Scoop survivor himself, Jobs has had his own experience returning to his home community of Tuktoyaktuk. (Natalie Pressman/CBC) "I just share with them how it was for me with my family welcoming me, but there was some rejection there as well," he said. "I think .

.. the misconception is people think we want something out of that when we come home.

We don't. We just want to meet 'em. I just want to know where I'm from.

" Jobs said after a childhood of being passed from home to home and growing up in a place where Indigenous children often don't look like their adopted family, that rejection can be especially triggering for children of the Sixties Scoop. "After a while, it doesn't feel like you belong anywhere," he said. Sariah Stanley and RavenSong Gargan paid their respects at the Fort Providence cemetery.

(Natalie Pressman/CBC) Joachim Bonnetrouge, an elder in Fort Providence and former chief of Deh Gáh Got'ı̨ę First Nation said the community members who are skeptical of welcoming the women home are facing their own journeys and can be suspicious of newcomers given the community's history of colonization. "It's natural because, you know, we've had quite a dark history," he said. "So that's what we're still dealing with.

" Elder hopes community will learn to welcome survivors In a federal Sixties Scoop settlement, 21,210 people were deemed eligible for compensation, according to Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, though the actual number of Indigenous children taken from their families is thought to be much higher. But the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in care didn't end with the Sixties Scoop. It's a battle Delphine says she continues to face as she fights with Child and Family Services for care over her grandson in Thunder Bay, Ont.

Joachim Bonnetrouge, an elder in Fort Providence, met with the sisters and led a prayer in the cemetery. (Natalie Pressman/CBC) She said she's been told she wouldn't be an appropriate caregiver because of her tumultuous childhood as a Sixties Scoop victim. More than half the children in care are Indigenous, census data suggests 74% of youth in care in Alberta are Indigenous.

Here's what 2 of them had to say Bonnetrouge said there are hundreds of children who were taken from Fort Providence and that the community will learn over time how to welcome them home in a good way. With the potential for thousands of survivors to return to their home communities, and hundreds in just Fort Providence, RavenSong said she hopes to establish a kind of protocol around what it looks like to welcome them home, hoping to avoid some of the feelings of rejection from her community. She said she hopes to come back to Fort Providence and establish a connection with the community.

The other sisters aren't yet sure whether they'll join her but all three sisters agree the trip has been one they will never forget. "A part of my soul and part of who I am is tied here," Sariah said. "And there's no escaping it.

".

Top

Sixties Scoop survivors journey home to N.W.T. to reunite with family, reconcile past

Three sisters who are all survivors of the Sixties Scoop have found each other and reunited in Fort Providence, a community they call home, for first time.