More Indian artistes need to know how they can use Gita and Natyashastra to crack down on the language divide being attempted politically The addition of manuscripts of the Bhagavad Gita and Bharat Muni’s Natyashastra to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register is a development of cultural significance and civilisational assertion not only for India, but for Krishna-bhaktas around the world and South-East Asian nations that celebrate the epics in the performing arts, visual arts, ancient temples and temple architecture. It is India’s moment to intensify intercultural dialogue through an amalgamation of the essence of the Bhagavad Gita and Bharat Muni’s Natyashastra for spearheading a global contribution to ‘stagecraft’ across domains and look for more than mere ‘recognition’. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has assertively restored the space for Gita as a “gift" to the world.

He said: “The Gita and Natyashastra have nurtured civilisation and consciousness for centuries. Their insights continue to inspire the world." Attainment of freedom by performing “swadharma" has been the essence and subject of human and intellectual pursuit inspired by the Gita—for millennia.

Bearing the gist of the Vedas, their science, the Gita is considered next to only the Upanishads in Bharatiya civilisation. Swami Vivekananda said: “Than the Gita no better commentary on the Vedas has been written or can be written." For centuries, the learned have believed that the essence of the Vedas is in the Upanishads and the essence of the Upanishads is in the Gita.

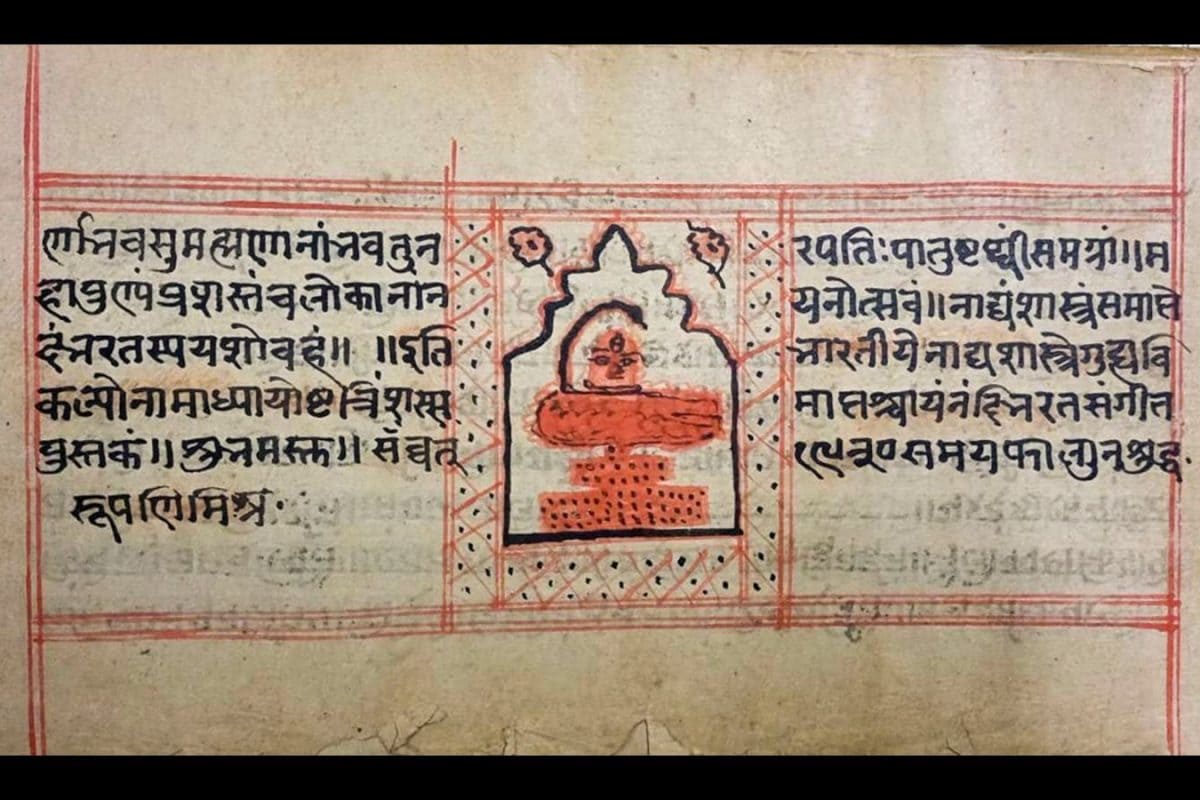

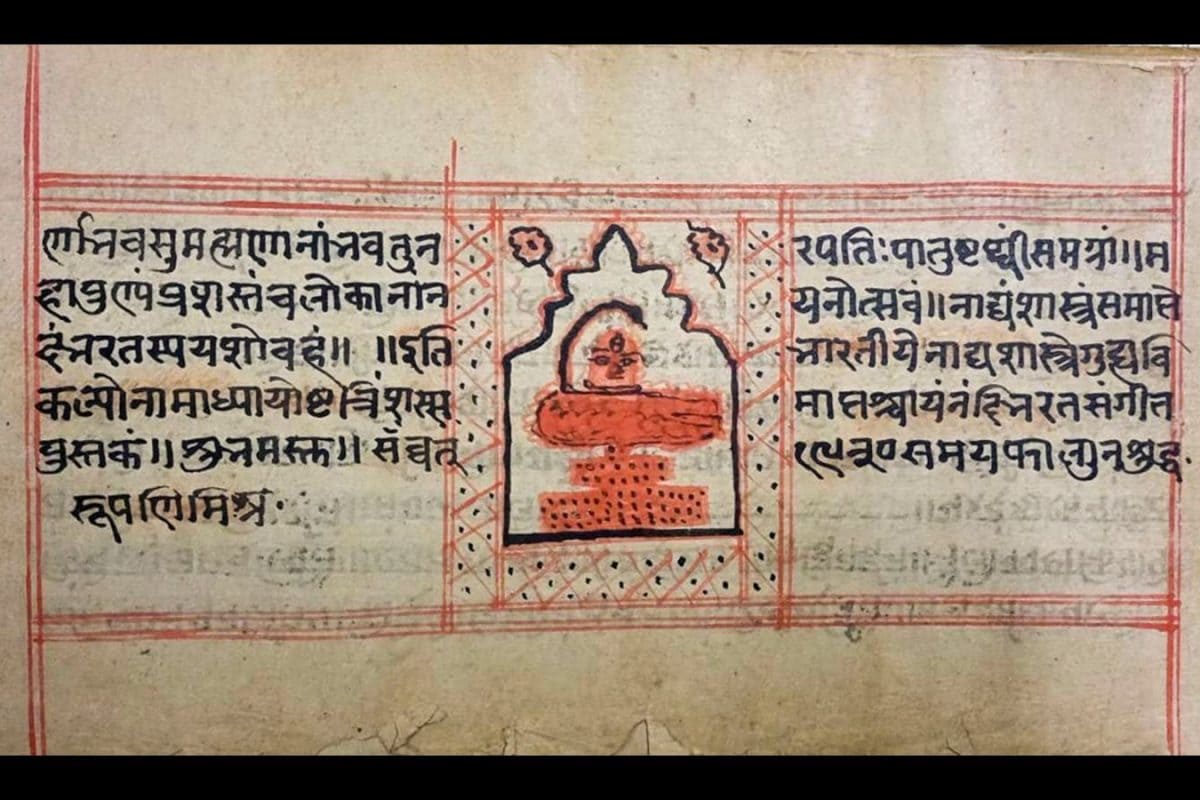

Swami Vivekananda established and restored the reason why the Gita matters to India and the world. Indian classical art, as a whole, nourishes itself. The manuscripts of the Bhagavad Gita and Bharat Muni’s Natyashastra getting added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register should motivate India to use this development as an indication to nourish public engagement with the two texts, explaining through commissioned works how nuances intrinsic to Indic classical art and variants have roots in Bharat Muni’s Natyashastra and the Natyshastra itself has its roots in the Vedas.

It’s time India drew attention towards Indian aesthetic, national reconstruction and rejuvenation to theatre and dance nourished by a deeper look into the Natyashastra through art that is “accessible to all". India has immeasurable wealth to share with the world on theatre building, rituals, ritualistic music, rasa, bhava, voice and meter, body, body language, costume, expressing and expression. But first, India must create for India.

The reasons why India must take this development as a new lease of material for creation are: Rasa, the essence of the four Vedas flows into Bharat Muni’s Natyashastra. Being able to portray, express, transmit, instill and propagate the consciousness of absolute reality in spiritual consciousness, spirituality, and aesthetic, in the language of the divine, has been possible for rishis of this great land. Preserving aspects that surpass sensorial comprehension, allowing the reintegration of sacred texts in human memory, civilisational and cultural memory, of the Upanishads, Vedas, the Mahabharata and the Natyashastra into Sanskrit drama, in the performing arts, classical dance forms offered to the divine, and theatre forms that thrive in the essence of the Natyashastra, is perhaps one of the reasons why the Indic civilisation survived repeated invasions that lasted centuries.

Civilisations that ran parallel to the Indic civilisation either faded away, disintegrated or witnessed their culture and soul disoriented and destroyed. The Natyashastra and the Bhagavad Gita signify the essence of “tanmayata"—the state of complete absorption, focused immersion, profound spiritual concentration, engagement and involvement with aspects of the human mind, spirituality, the sacred, and art centered on the pursuit of beauty, truth and the spiritual. Krishna is worshiped as the preserver, representative, practitioner, manifestation and propagator of the arts, among them, the performing arts.

The intricate relation between expression and conversation in the form of a heartfelt and cerebral discourse between the one who imparts knowledge and those who seek knowledge is at the core of the Bhagavad Gita and the Natyashastra. The seed of the Natyashastra is Brahma and of the Bhagavad Gita is Krishna—a manifestation of Vishnu. Brahma represents Srishti—creation and creating, while Vishnu performs Stithi—preservation and sustenance.

The Bhagavad Gita and Natyashastra delineate the significance of roles. Krishna, as the Sarathi, leads Arjuna—the Kshatriya, warrior, brother, son, father, husband. The Natyashastra can allow the world to explore how the system of thought in Bharatamuni’s work can help reveal Arjuna in these different roles at a given time, in the given role, on the stage—the intimate stage.

The meaning, expression, revelation, embodiments, disclosures, declarations, strengthening and expressing of allusions, and personifications of roles in context as well as content might differ in the two, but the roles have to be performed with a steady and focused mind with attaining wisdom in varying manifestations. The contemplation on roles will guide the global audience to India’s own bhoomika [role] as the seat of highest human attainment in the ancient times in the current scenario. The addition of the manuscripts of the Bhagavad Gita and Bharat Muni’s Natyashastra to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register can direct the world to ask and repeat the questions.

“For whom?", “By whom", “Why", through an integration of the two of the highest texts of Indic civilisational heritage of sacred, spiritual, art and intellectual value in their life, expression, work and culture. The three questions will divulge an ocean of perspectives on India as the land that can unlock the realm of “purpose" behind art, Sanatan, sacred and philosophy, physical and metaphysical. They signify discipline in the context of vidya and vidyas (knowledge, wisdom, and the arts), compelling the human mind and body for an unceasing exploration of subjects as a whole, in totality and for the synchrony in essence of the true action, the right action, right choice— whether through life led in dharma or through life led in art entrenched in the sacred.

The Bhagavad Gita and Natyashastra present the genesis of beauty and truth and their meeting, above and beyond the mundane in life, which can be of timeless value to a 21st century rapidly evolving, chaotic, dystopian, technology-altered, commotion, war-challenged, tariff-threatened, and strife-prone world. They guide and shape life choice, offering a higher state of awareness of truth and beauty to be experienced by the mind, body and inner self. The reading of The Bhagavad Gita and Natyashastra encourages a deeper engagement with “action".

Action on the battlefield of Kurukshetra—towards attaining the knowledge of unmanifested eternal and the manifested Ishvara, through the understanding of the fruit of action with performance. Natyashastra takes the reader and artiste towards action on the stage, through abhinaya, the nourishment of self as a human and artiste, as audience, towards absolute reality through spiritual deliberations. The engagement of the mind in action (kriya) ensures greater opportunity and devotion (to the Supreme self) and higher consciousness.

Sadhana is the focal point in achieving these spiritual, creative and ingenious goals, bridging the mind, practice and augmented achievement through movement and meaning. The world requires historically informed spiritual answers from India’s abundance in the expression of eternal principles and the expression of Ananda (bliss). The Bhagavad Gita and Natyashastra connect the spatial quest of the human mind with the concept of space and time—in lifelong query of bhakti in action.

For centuries, India has been the source and pilgrimage for a global audience. The basis and fountainhead of this audience has been the collective pull and power of the Bhagavad Gita and the Natyashastra, the integration, infusion, and immersion of these two sacred texts in all aspects of spiritual, cultural, and cerebral engagement and exponentiation in literature and art in India. The 21st century world needs to witness how India puts the two texts to practical application in human life, academic temperament, technique and subject matter in humanities, innovation in education and arts in education.

Appalling or morbid even, it may sound to the West, but these two texts are complete in themselves as spiritual instruments and might come handy in comforting human life in death and devastation caused by calamities designed by man or nature. Bhagavad Gita alone, Natyashastra alone, and their gargantuan combination, have the capacity to make forces inimical to human sustenance in India, across India’s borders to the West and East, and in the West. During the 10 years of Modi’s rule, celebration of the Bhagavad Gita has been carried out the most assertively in India, in Modi’s own strategic outreach, and India’s global dialogue.

What should happen next is a distinct amalgamation of the essence of the two texts in Indian soft power. Directly or indirectly, the two texts have compelled art responses from performers. The cross fertilisation and inter-cultural dialogue attempted by American pioneer in dance, Ruth St.

Denis, is a subject of awe and inspiration for dancers in the West for her use of Indic influences, steps and movements, Radha’s role, the amalgamation of theatre and dance, sometimes callously termed ‘Asian’. In the early 1920s, Anna Pavlova, one of the most well-known ballerinas, wanted to understand Indian dance. She called upon Uday Shankar, who was a student of visual art at that time.

The two named their performance ‘Oriental Expressions’. Pavlova-Shankar partnership would feature Pavlova as Radha and Shankar as Krishna. Another work was titled A Hindu Wedding.

Shankar would be so mesmerised by his own language of movements unfolding in their partnership and explorations in retelling through dance that he toured with Pavlova’s troupe and planted a seed of modern Indian dance in Almora. The western view of the ‘Orient’ would get redefined with the glimpse of Balinese theatre and the influence, tracing its roots to India, to the great epics, to the codified body language. While cross-fertilisation prompted the interest and curiosity of the West in Indic dance in general, the great practitioners of Bharatanatyam and Odissi and their compelling art would make dancers from across the world turn towards India and the study of Bharat Muni’s Natyashastra.

Myrta Barvie, the iconic world-renowned Argentinian dancer, opened the path for Indic arts in Argentina, connecting Latin America with India. She was 17 when she visited India’s Kalakshetra and continued the chain of intercultural dialogue through Indic dance forms by inspiring Natalia Salgado and Patricia Salgado. The Salgado sisters propagate Bharatanatyam, Odissi and Kuchipudi in Argentina and Spain through an institution that celebrates the Indic spiritual and sacred in Indic art as soul and whole.

India, individually as well as in partnership with the ASEAN nations practising Bharatiya traditional arts, and their preservation in theatre, dance and the performing arts, must play the role of a capacity-building leader in the use of the insights in and on Gita and the Natyashastra as a solution to solving global challenged in international dialogue, culture, education and arts in education, and in enhancing and enriching learning experience, using the art of retelling and redoing, digital learning tools, Artificial Intelligence, and above all, performance itself. More people in the world might know about Aristotle, his work, than they know Bharat Muni and Natyashastra. More Indians need to know how the Natyashastra has inspired works and dance forms in peninsular India.

More Indian artistes need to know how they can use Gita and Natyashastra to crack down on the language divide being attempted politically. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

.

Politics

Opinion | Why India Should Look Beyond UNESCO ‘Recognition’ For Bhagavad Gita And Natyashastra

More Indian artistes need to know how they can use Gita and Natyashastra to crack down on the language divide being attempted politically