Now that I have crossed that threshold of three score and ten years, I think I qualify to reflect on the past. While like Macbeth , I have seen many strange and dreadful things like assassinations, social upheavals, natural disasters, and a pandemic, unlike the doomed king, I have also seen many splendorous rainbows against history’s cerulean sky. One of the lessons I have imbibed is that the past is an effective tool to lend perspective and clarity to events in the present, and it’s pointless to negate that.

The socio-economic changes we see today are remarkable. Nothing of this was foreseeable in the time immediately after Independence. The Partition had happened, but our State, Kerala, remained unaffected and calm through all the turmoil.

Gandhiji’s assassination was an altogether different matter as its trauma was felt everywhere, but Jawaharlal Nehru had boldly stepped into the void left by Gandhi to hold things together. Nehru in Kerala The State of Kerala came into being in 1956, when I was in class I. Travancore, Kochi, and Malabar were integrated to form the new State.

Kochi was the smallest and comprised only two districts, Thrissur and Ernakulam, to which we belonged. In my early days, while public libraries, schools, and district hospitals were available, other infrastructure was poor. Roads and public transportation were inadequate.

There was only one interstate train, the Cochin-Madras Mail. We had no radio. For news, we read Mathrubhumi and The Hindu , both steeped in the ethos of the freedom movement.

Nehru was the central figure nationally: his views and decisions were always reported in both the papers. The only visual medium I could access was the Films Division‘s short documentaries called the “Indian News Review”. I watched many of them, and Nehru was invariably there, walking briskly, inspecting the progress of work at the Bhakra Nangal Dam, meeting Homi Bhabha and other nuclear scientists, or talking to foreign dignitaries.

At times he was there at the Himalayan foothills mingling with local people or talking to schoolchildren. Also Read | How Jawaharlal Nehru’s death marked the end of an age of innocence When he spoke on screen, I listened intently to that earnest voice, with its ring of deep sincerity. His voice was no baritone.

But he had a clipped accent and a matter-of-fact delivery. Sometimes I couldn’t comprehend what he said. But I sensed an urgency, even impatience, in his movements.

Our English teacher told us that Nehru liked Robert Frost’s poetry. So, perhaps, he was acutely aware that he had promises to keep and miles to go before he could sleep. Throughout those days of hope and aspirations, Nehru was a benevolent, intangible but felt presence in our young lives.

However, I could never see him in person; surely, he could not be expected to come to that faraway place where we went about our lives? All that changed one summer evening as we sat down to dinner. In those days we were living in Eloor, now known as Udyogamandal, which had Kerala’s largest industrial complex on the banks of the Periyar river. It was primarily a chemical industrial complex with many factories on the riverbank.

My father worked in one of them. The river was wide and full, just a few kilometres away from its mouth where it joined the backwaters and then the Arabian Sea. One could always see tugs and barges carrying fertilizer to Kochi harbour.

Dredgers constantly desilted the river. Our houses were situated on the banks of the river, on a gradient. It was a well-laid-out, self-contained industrial township, the New India of Nehru’s vision.

On the far bank, tall chimneys spewed smoke. It was the month of March, school holidays had begun, and we were to leave for Thrissur, our hometown, the next day. Then father grandly declared at dinner that Nehru was coming to Eloor the next day to address a public meeting.

The Eloor-Edayar industrial area on the banks of the river Periyar near Kochi in 2021. | Photo Credit: THULASI KAKKAT Excited, I walked next morning to the factory gate area where a crowd of 500 or so had gathered. Most of them were workers who had no shift duty, some were from the surrounding villages, and a few were from our township.

The heat was searing on a windless day. I found a place in the shade. There were white khadi–clad Seva Dal workers in their distinctive white topis arranging the podium and checking the sound system.

Unlike today, although Prime Minister Nehru was the speaker, the atmosphere was relaxed and people walked around freely. There was no overbearing security. It was 1957, the time of the second general election.

Nehru was campaigning everywhere. I still don’t know why he chose to come to our small township. It might be because communism was on the rise in Kerala, and he wanted to speak to the industrial workers.

Later, in 1957 itself, a communist government was formed in the State under E.M.S.

Namboodiripad . Following Nehru Nehru’s motorcade drove in at noon: just a police jeep and a few cars. He himself was in a large, roofless Plymouth car, waving to the people.

He walked briskly up the steps to the podium, which was not far from where I stood. Some local party leaders spoke first, followed by U.N.

Dhebar, the Congress’ national president. And then Panditji took over. Someone was translating his speech into Malayalam.

Nehru spoke fast and clearly: I could easily recognise that clipped accent and effortless choice of words that I had heard many times before in the Films Division’s news reels. He didn’t seek votes but explained to the people what the Central government was trying to do. I couldn’t fully grasp all that he said, but most certainly he had a tremendous presence—his slender frame radiated energy.

Immediately after his speech, Nehru’s motorcade sped away to his next destination, and I came home. That evening, after father returned from work, we left for Thrissur in a taxi. Although the distance to cover was only about 50 miles, the road was not good.

There were four railway crossings and a very wide stretch of the Periyar river to cross on boat after the town of Aluva. There was no bridge over the river and catamarans were used. All this took time.

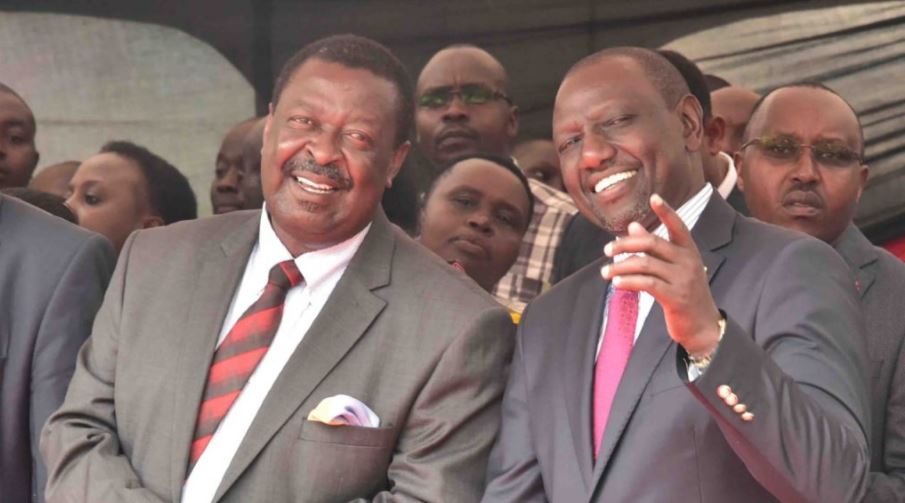

Nehru with E.M.S.

Namboodiripad and members of his Cabinet in 1957. | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives As we hit the national highway, we knew that Nehru’s convoy had gone ahead of us. The highway was full of Congress party banners, festoons, and flags fluttering in the light of the fading evening.

At places we had to slow down because ahead of us the Prime Minister’s convoy was passing. We were told that he was also heading to Thrissur for a night rally. By the time we crossed the Periyar in a catamaran, it was dark.

We passed many small towns like Angamaly, Chalakudy, Puthukkad, and Ollur on the way to Thrissur. In 1957, these were small habitations of a few thousand people. Nehru stopped and briefly addressed the waiting crowds.

At Chalakudy, a bigger town, the meeting was in a clearing by the roadside. As our taxi passed, I could see the place brightly lit up by Petromax lights. Music was blaring.

The air was festive. Also Read | Aditya Mukherjee’s forensic defence of the Nehruvian ‘Idea of India’ When we reached Thrissur town at about 10 pm, the famous Swaraj Round and Thekkinkadu Maidan were packed. Nehru was addressing a sizeable crowd in this town of temples and palaces.

Thrissur was the second capital of the old Kochi State, and the Congress still had popular support there. From the moving taxi, I could glimpse the outlines of the great Siva temple Vadakkunnathan against the sky. Nehru’s voice rose over the din and the darkness.

Overarching presence Nehru and the Congress won the 1957 general election. I never got a chance to see him afterwards. He would have come to the State again but not to our township.

As usual, I saw his photographs in newspapers and newsreels in movie halls. We now had a radio in our home, and his voice often wafted in. When he came again in 1964, after May 27, one couldn’t see him any longer but still feel his overarching presence.

It was early June, and the monsoons had broken. It was a bright, very hot, rainless, sweltering day when we students waited by the roadside in Kalamassery for the motorcade carrying his ashes to pass. It was moving along the same national highway that we had traversed in early March 1957.

A sound system, mounted on a truck, was playing Gandhiji’s favourite prayer, “ Raghupati Raghava Rajaram” . The human chain paying homage extended right up to the Bharatapuzha river, where his ashes were immersed. An era had passed.

A year later, as I began to read The Discovery of India, I realised what a seminal mind had passed into history. P. Krishna Gopinath is a Delhi-based writer with an interest in photography and Western classical music.

Featured Comment CONTRIBUTE YOUR COMMENTS SHARE THIS STORY Copy link Email Facebook Twitter Telegram LinkedIn WhatsApp Reddit.

Politics

Nehru comes to town

India’s first Prime Minister spoke fast and clearly. I couldn’t fully grasp all that he said, but he certainly had a tremendous presence.