I once met a person raised in a military family. She spoke of frequent dislocation and how much she envied folks like me raised in a settled place, a hometown, no matter how small. She was right.

Hometowns. There’s something about them: you can’t get them out of your head, nor would you want to. They’re attached to you, part of you, like the color of your eyes or a ring on a finger you never remove.

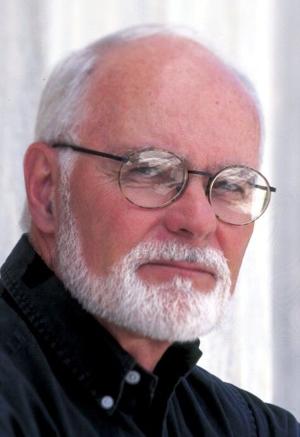

Jack Peradotto has both fond and terrifying memories of his hometown. Buffalo is my hometown now and I cherish her. But the hometown in my heart of hearts, the one that shaped my young life was Ottawa, a smaller place set in the Illinois plains some 90 miles south of Chicago.

Ottawa is where the placid Fox River flows into the turbulent Illinois, whose rough waters have gouged a deep cleft in that flat farmland, revealing either side steep sandstone cliffs. The gentler Fox's sloughs and backwaters served up a childhood playground rich in wildlife and indelible in memory. I left Ottawa in my teens but it glows more brightly in memory than any place I’ve lived in since, so much so that I will frequently defeat insomnia, not by counting sheep, but by a quiet mental re-creation of my boyhood newspaper route that took me meandering along the town's main streets, over its bridges and up the alleys I used as shortcuts.

Then past the convent of the Sisters of Mercy where their dark shapes, beads in hand, strolled its quiet courtyard two by two, praying for the war to end. Finally, I’m home, one paper left in my bag, its front page mostly about the war. Someplace far away.

A tidy, sanitized dream of childhood, you will say. And to be sure, memory does tend to have that drug-like effect. But I’ve come to know that hometowns, like the folks that live there, have their dark sides.

Ottawa’s dark side is notorious, refreshed in memory by Kate Moore’s 2017 book “Radium Girls: The Dark Story of America’s Shining Women.” As a boy this horror would have been hidden from me, except that a best friend in school was the son of Catherine Donohue, one of the victimized women who, though dying, led the legal struggle that would expose this outrage and bring it crashing down. It is not a pretty story.

In the 1920s, young women like my friend Tom’s mother were recruited to work in the Radium Dial factory in Ottawa to paint radioactive glow-in-the-dark watch faces and aircraft gauges. They were instructed to lick their brushes to a fine point for greater precision and were further told that this was not only safe, but hygienic. These women would go on to suffer disfigurements.

Many, like Tom’s mother, would die. When the factory was finally demolished, its radioactive rubble was actually used for landfill throughout the Ottawa area. To this day, one finds a high incidence of birth defects there, and hunters report sightings of deer and other wild game grotesquely deformed.

There are currently 16 radioactive EPA Superfund sites in my hometown alone. Despite all that and without discounting its awfulness, I stubbornly refuse to give up thinking tenderly of my hometown. And yet, on those sleepless nights when my imagination revisits my boyhood paper route, I give the ruins of that infernal factory a wide berth.

And since I myself once played kick-the-can and capture-the-flag on its toxic rubble, and walked to grammar school daily across what would later be designated an EPA Superfund site, I glance at my hands to make sure they are not glowing in the dark. Catch the latest in Opinion Get opinion pieces, letters and editorials sent directly to your inbox weekly!.