Ménière’s disease (MD), named after French physician Prosper Ménière, who identified the condition in 1861, is an inner ear disorder causing tinnitus, vertigo, and hearing loss. It affects approximately 615,000 people in the United States, representing about 0.2 percent of the population, and around 45,500 new cases are diagnosed annually.

However, there is ongoing debate about the true prevalence of the disorder. MD is also called endolymphatic hydrops. Definite MD Vertigo episodes: Two or more spontaneous episodes lasting between 20 minutes and 12 hours.

Hearing loss: Documented low- to medium-frequency sensorineural hearing loss in one ear before, during, or after a vertigo episode. Fluctuating aural symptoms: Examples include hearing loss, tinnitus, and ear fullness in the affected ear. Exclusion of other causes: No other vestibular disorder explains the symptoms.

Probable MD Vertigo: Vertigo is an intense false perception that the individual, the surroundings, or both are moving or spinning, and it may lead to severe nausea, vomiting, and sweating. It can also lead to tinnitus, temporary hearing loss, and a sensation of fullness in the ear. Many people describe this unsettling sensation as “dizziness.

” A typical episode may last several hours, with fatigue or imbalance lingering after the vertigo subsides. Vertigo attacks occur unpredictably. Symptoms worsen with sudden movement, often requiring the patient to lie down and close their eyes for relief.

Drop attacks: Vertigo can become so severe that the patient loses balance and collapses. These incidents are known as “drop attacks.” It may feel as if one is suddenly being thrown to the ground.

Individuals experiencing these drop attacks do not lose consciousness and typically recover within seconds or minutes. Hearing loss or muffled hearing: In the early stages of Ménière’s disease, hearing loss may be mild or fluctuate. In later stages, it can become severe and permanent.

Although hearing gradually declines, MD rarely leads to deafness. Tinnitus: Tinnitus is a ringing in the ear that may present as a constant or intermittent buzzing, ringing, roaring, whistling, or hissing sound. It often occurs due to hearing loss, and many patients also feel pressure or fullness in their ears, which may intensify before or during a dizzy spell.

Difficulty hearing low frequencies: Low-frequency hearing loss typically occurs first, followed by a progression to other frequencies. Vowels correspond to lower sound frequencies. Pressure or fullness in the affected ear: The affected ear may feel full or plugged up, similar to a eustachian tube issue.

This sensation often worsens just before a dizziness attack, potentially serving as a warning sign. Nystagmus: Nystagmus is uncontrollable eye movements. These movements can reduce vision and depth perception, affecting balance and coordination.

They may occur side to side, up and down, or in a circular motion, making it difficult for both eyes to focus steadily on objects. Hyperacusis: This means sensitivity to sounds. Distorted sounds or abnormal hearing.

Tullio phenomenon: The Tullio phenomenon sometimes occurs. It is characterized by the onset of vertigo and nystagmus triggered by loud noises. Diarrhea.

Loss of balance. Earache. Headaches.

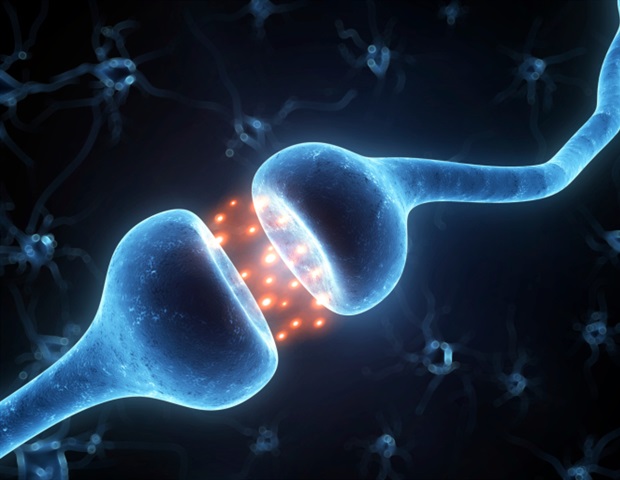

Abdominal pain or discomfort. The Essential Guide to Tinnitus: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments, and Natural Approaches Lupus: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments, and Natural Approaches The inner ear has two distinct compartments filled with different fluids, perilymph and endolymph, which surround hair cells that detect sound and motion. Endolymph is produced in the cochlea and normally reabsorbed by a part of the inner ear called the endolymphatic sac.

Fluid in the inner ear is typically distinct from the body’s overall fluid system and has specific concentrations of sodium, potassium, and chloride. However, in MD, the volume and concentration of inner ear fluid fluctuate with the body’s fluid levels. Over time, these abnormal fluid concentrations can lead to irreversible damage to the sensory cells responsible for hearing and balance.

If the endolymphatic sac fails to remove sufficient endolymph, it leads to swelling that stretches the membranes, causing ear pressure, tinnitus, and hearing loss. In a healthy ear, endolymph in the cochlea is compressed in response to sound vibrations, activating sensory cells that transmit signals to the brain, where hearing occurs. However, an accumulation of endolymph disrupts this normal function.

This affects hearing in individuals with MD. Over time, repeated episodes can result in stretched and floppy membranes, and the inner ear can become so filled with fluid that there is no room for pressure fluctuations, leading to acute episodes tapering off or stopping altogether. However, the excess fluid continues to affect balance adversely and hearing in a more persistent and chronic manner.

There are various theories regarding the causes of endolymph buildup, although, in most patients, the exact cause remains unidentified. The disease probably has a combination of causes, such as genetics and environmental factors. For instance, an irregular inner ear shape or blockage may lead to poor endolymph drainage.

Stress Excessive work Fatigue Emotional distress Other illnesses Changes in pressure Certain foods High sodium or salt intake in the diet Age: MD can occur at any age, but it is most commonly found in adults aged 40 to 60. It is significantly rarer in children and young adults. Race or ethnicity: People of European descent are more likely to develop it.

Autoimmune or vascular diseases: The disease is linked to autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Additionally, vascular diseases can cause blood vessel constriction, which raises the risk of MD. Respiratory or viral infections: Viruses linked to MD are neurotropic viruses, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, varicella-zoster virus (chickenpox), and cytomegalovirus.

Family history of MD: Though less likely, MD can be familial, suggesting that a genetic mutation may be inherited from parent to child. When the disease is familial, it typically follows an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern, meaning one altered gene is enough to increase the risk. However, no specific genes have been identified.

Smoking: Blood vessel constriction, which smoking causes, can lead to an insufficient blood supply to the nerves connecting the inner ear and brain that regulate equilibrium and balance. Head injuries: MD has been reported to develop following head trauma, particularly injuries that affect the inner ear. Sex: Females may have more of a risk than males.

The condition occurs more frequently in older white female patients. However, some researchers believe the likelihood of developing the disorder is relatively equal between women and men. Allergies: Allergic factors can harm the inner ear.

The disease is diagnosed based on its symptoms, as no specific test can definitively confirm it. A thorough otologic history is essential when investigating hearing or balance issues. A health care provider (such as an otologist) should ask the patients about the nature of their vertigo to distinguish true spinning vertigo from general imbalance or lightheadedness.

Questions should also cover hearing loss, previous episodes, duration of symptoms, and any positional triggers. In addition, a family history of hearing and balance problems should also be explored. Neurologic examination: The cranial nerves should be checked to identify additional focal abnormalities.

Fukuda stepping test: In long-standing or resistant cases with labyrinthine dysfunction, the Fukuda stepping test (marching in place with eyes closed) causes the patient to turn toward the affected ear, indicating a labyrinthine lesion on one side. Halmagyi head thrust maneuver: The Halmagyi head thrust maneuver, or head impulse test, is also used to assess one-sided labyrinthine dysfunction. In this test, the patient concentrates on a target.

At the same time, the examiner rapidly rotates the patient’s head 15 to 30 degrees to one side, observing the patient’s eye movements for signs of vestibular dysfunction. Rinne and Weber tests: Rinne and Weber tests use tuning forks to test a patient’s response to vibrations close to the ears, providing a basic assessment of auditory nerve function and can detect sensorineural hearing loss. However, a formal audiology evaluation is required due to variability based on the severity of hearing loss.

Orthostatic blood pressure measurement: This refers to the assessment of blood pressure changes when a person moves from a lying or sitting position to standing. Dix-Hallpike maneuver: The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is a test for diagnosing benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). The patient’s head is rotated to one side, hyperextended, and then the patient rapidly transitions from sitting to lying down.

The eyes are observed for rotational nystagmus and vertigo symptoms. The test is repeated with the head turned to the opposite side. Frenzel goggles may help identify nystagmus.

Brainstem evoked response audiometry (BERA): This noninvasive test involves placing electrodes on the patient’s scalp and earlobes and providing auditory stimuli. The brain’s responses to the stimuli are then recorded. Electronystagmography (ENG): Electronystagmography records eye movements, helping the doctor check balance and identify the source of the problem causing vertigo.

Electrocochleography (ECOG): Electrocochleography measures fluid pressure within the inner ear. Caloric vestibular test: A caloric vestibular test assesses the function of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) by examining the horizontal semicircular canals of the inner ear. Videonystagmography (VNG): Videonystagmography assesses balance function by examining eye movements.

Rotary chair testing: This test also evaluates inner ear function by analyzing eye movements. Posturography: Posturography is a computerized test that identifies which components of a patient’s balance system—vision, inner ear, or proprioception (sensation from skin and muscles)—the patient relies on for stability. While wearing a harness, the patient stands barefoot on a platform and attempts to maintain balance under different conditions.

MRI: Patients with unilateral (one-sided) hearing loss should undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to exclude retrocochlear pathology, which is any condition that affects the brain, brainstem, or auditory nerve (such as multiple sclerosis) and to detect the presence of a tumor. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI: Gadolinium is a heavy metal used as a contrast dye. X-rays.

Blood tests. Two or more spontaneous episodes of vertigo lasting 20 minutes to 12 hours Hearing loss for low- to medium-frequency sounds in one or both ears, confirmed by a hearing test conducted before, during, or after a vertigo episode Irregular hearing-related symptoms Symptoms not explained by another diagnosed balance-related condition Sudden vertigo attacks. Long-term hearing loss.

Anxiety: This is because the condition can occur unpredictably. Risk of falls and accidents: Vertigo may disrupt a patient’s balance. Damaged inner ear: For some patients, each vertigo attack can harm their inner ear, causing significant damage over time that affects its proper function.

Roaring or hissing in the ear: The vertigo attacks may eventually cease, but certain symptoms, such as roaring in the affected ear, may remain. Otolithic crisis of Tumarkin: In the later stages of the condition, patients may experience sudden, unexpected otolithic crises of Tumarkin, otherwise known as drop attacks, without losing consciousness. Depression: Patients experience a significantly higher rate of depression compared to the general population.

Attack Prevention Avoid triggers: A key aspect of managing the condition is identifying and avoiding behaviors or exposures that trigger attacks. For instance, caffeine, alcohol, and smoking are known to worsen Ménière’s disease and should be avoided. Restrict sodium: Salt intake can influence inner ear fluid pressure.

People with Ménière’s disease often experience attacks 12 to 48 hours after consuming high-sodium meals. A low-sodium diet, with less than 1.5 grams per day, is recommended to help manage the condition.

Consider thiazide diuretics: Thiazide diuretics are a common treatment, as they help reduce the frequency and severity of symptoms. However, they do not prevent hearing loss. Combined with a low-salt diet, they can further lower fluid pressure in the inner ear.

Attack Treatment Antiemetics: Antiemetics help reduce nausea during an acute attack and can provide significant relief. They are often more effective when taken early in the attack as rectal suppositories, allowing the medication to be absorbed and preventing vomiting before other medications can take effect. Vestibular suppressants and sedatives: Meclizine, lorazepam, diazepam, and clonazepam help alleviate symptoms of acute balance disturbances by reducing abnormal inner ear signals to the brain and relieving anxiety.

Among them, meclizine is the most frequently prescribed for managing vertigo and is available over the counter. These medications are often taken after antiemetics to ensure absorption, and in severe cases, they may be administered via injection for faster relief. Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) is also available over the counter, with less effectiveness than meclizine.

In cases where other medications do not adequately control vertigo, small doses of diazepam (Valium) may provide relief. Gentamicin injection: Gentamicin, typically an antibiotic, can selectively eliminate the inner ear’s balance function while preserving hearing. This is done through a series of injections through the eardrum in a medical office.

Around 80 percent of patients benefit from this treatment. However, due to its toxicity toward cochlear cells, gentamicin’s potent effects on vestibular cells can lead to side effects, including sensorineural hearing loss. Steroid injection: Dexamethasone , a potent steroid, can be injected into the inner ear to treat severe MD, although the effects are not permanent.

However, compared to gentamicin, it carries a lower risk of hearing loss. In some cases, steroid injections can even improve hearing. Surgery Endolymphatic sac or shunt surgery: The endolymphatic sac, a part of the inner ear, is believed to play a central role in MD by regulating endolymphatic fluid reabsorption and inner ear pressure.

The surgery aims to decompress the inner ear fluid by incising the sac. This procedure is considered safe with a short recovery time. Removing surrounding bone and scar tissue can help some patients better manage their inner ear pressure, thus leading to fewer vertigo attacks.

Vestibular nerve section: Vestibular nerve section is performed through an incision behind the ear, where the balance nerve is located between the ear and the brain. The balance fibers are separated from the hearing nerve fibers and then cut, preventing the brain from receiving abnormal signals during acute vertigo attacks. This procedure is highly effective, providing complete relief from vertigo for over 90 percent of patients while preserving hearing at preoperative levels in about 80 percent of cases.

Labyrinthectomy: A labyrinthectomy involves completely removing the organ of balance (the labyrinth) by destroying the balance canals and thus permanently eliminating the source of vertigo. While it has the highest cure rate for vertigo, it always results in total hearing loss in the operated ear and is only recommended for patients with very poor hearing. Rehabilitation Hearing aids: Hearing aids can be used to address hearing loss.

Amplification devices can redirect hearing from the weaker ear to the stronger ear. Implantable hearing devices such as bone conduction amplification and cochlear implants are also available. Physical therapy.

Vestibular therapy: Vestibular therapy is a specialized type of physical therapy designed to enhance the balance function of the inner ear and the central nervous system (brain). Positive pressure therapy: Positive pressure therapy involves inserting a tube into the ear connected to a pump, which creates waves of pressure that may help alleviate some symptoms of MD. Therapies for mental health: Stress and intrusive effects caused by the condition can lead to an increased susceptibility to depression and anxiety.

Mental health therapies may include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based stress reduction, acceptance and commitment therapy, and hypnosis. Self-Care Lie down and keep the head completely still until the attack subsides. Take medications for vertigo and nausea right away.

Refrain from making sudden movements, as they may exacerbate symptoms. The patient might require assistance walking during attacks. Steer clear of bright lights, television, and reading during attacks, as these can intensify symptoms.

Perform exercises to enhance balance, which can help lower the risk of falling. Make changes in daily life to minimize the risk of injury during a vertigo attack. For instance, one can install grab bars in the bathroom, install a shower or tub seat, discard throw rugs at home, wear shoes with low heels and nonslip soles, and think carefully before driving, swimming, climbing ladders, and operating dangerous or heavy machinery.

Carry necessary medications all the time. Keep driveways, sidewalks, and other pathways free of obstacles that could lead to tripping. Stress and anxiety management: A negative mindset can increase stress and stress-related hormones, thus triggering vertigo episodes and worsening symptoms.

Conversely, a positive outlook can encourage coping strategies such as mindfulness, helping to manage stress and reduce vertigo attacks. Treatment adherence: A constructive mindset boosts motivation to follow treatment plans and explore complementary therapies. Social support: A supportive social network can enhance mindset.

Engaging with support groups helps patients feel less isolated and improves coping skills. 1. Diet Water: A small 2006 clinical trial showed that MD patients who drank 35 milliliters per kilogram of body weight (about 1.

2 ounces per 2.2 pounds) of water for two years had improved vertigo and hearing. The researchers suggested drinking enough water may be the simplest and most cost-effective way to treat MD.

Gluten-free diet: In a case study published in 2013, a 63-year-old female MD patient followed a restrictive gluten-free diet for six months, and her symptoms subsided, including the full resolution of vertigo and ear-related symptoms. However, as this was a case study with one person, it’s unclear whether the resolution of symptoms was spontaneous or occurred due to the diet. Specially processed cereals: In a 2020 study , 13 patients with MD were treated with specially processed cereals (SPC) that boost the body’s natural production of antisecretory factors.

Meanwhile, another 13 received intravenous glycerol and dexamethasone over 12 months. The SPC group showed a slight improvement in overall symptoms during the second half of the year, while there was a significant reduction in tinnitus. Overall, these patients had fewer vertigo attacks (61.

5 percent reduction) than the second group (30.8 percent reduction). Turkey tail mushrooms: In a 2023 study , after taking a daily dose of 3 grams (three 500-milligram tablets taken in the morning and evening) of Coriolus versicolor (turkey tail) for three to six months, 30 MD patients reduced oxidative stress in the body and improved cellular stress responses.

This treatment also decreased the number and duration of attacks, reduced symptom frequency, and improved tinnitus severity. 2. Medicinal Herbs Service tree (Sorbus domestica): Service tree is a rare, medium-sized leaf-shedding tree originating in southern and central Europe.

In a 2024 study , gemmotherapy, which uses extracts from a service tree’s young plant tissues such as buds and roots, was used to treat six MD patients aged 62 to 81. Within three days, all patients showed improvement in hearing and vertigo. Four experienced complete symptom resolution, while the others had significant improvements.

The treatment also led to a quicker and more effective recovery. Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba): A 2021 review examined 17 randomized controlled trials on the effectiveness of ginkgo extract for vertigo and tinnitus. Of the nine studies focusing on both tinnitus and vertigo/dizziness, eight reported improvements, and six of the eight studies investigating only tinnitus showed positive effects.

Milkvetch (Astragalus): In a 2022 study , 13 MD patients aged 42 to 79 took 7.5 grams of Boi-Ohgi-To (Astragalus decoction) daily for six months. The results showed that 69 percent of the participants experienced improvement in dizziness/vertigo, 30 percent improved in hearing, and 69 percent had overall improvement.

Ginger (Zingiber officinale): In an older study involving eight healthy participants, powdered ginger root significantly reduced induced vertigo compared to a placebo. 3. Chiropractic Care 4.

Acupuncture 5. Tai Chi Avoiding triggers and following a low-sodium diet can help prevent vertigo episodes for MD patients..