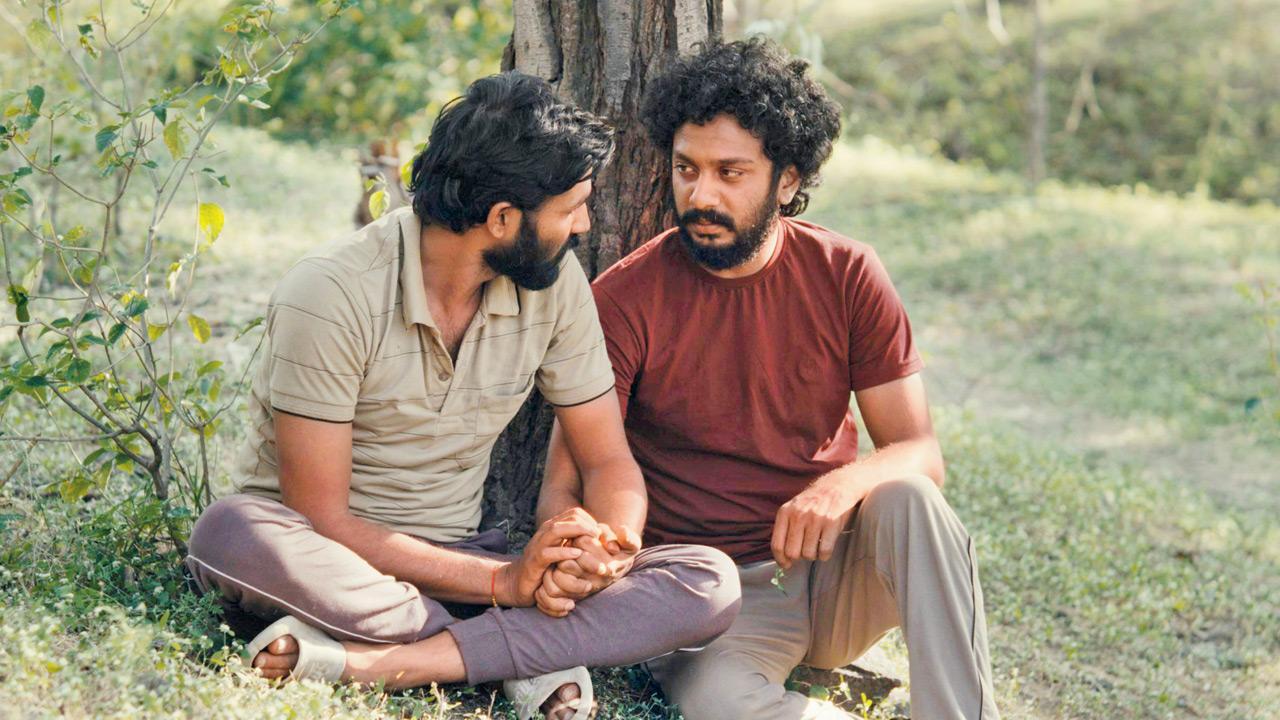

As against the big/theatrical screen, the laptop hardly captures human stillness well. I realised this in the opening shot of Rohan Parashuram Kanawade’s Sabar Bonda (Cactus Pears), when the camera zooms-in for long on the resting face of the lead character (brilliant Bhushaan Manoj). Nothing moves.

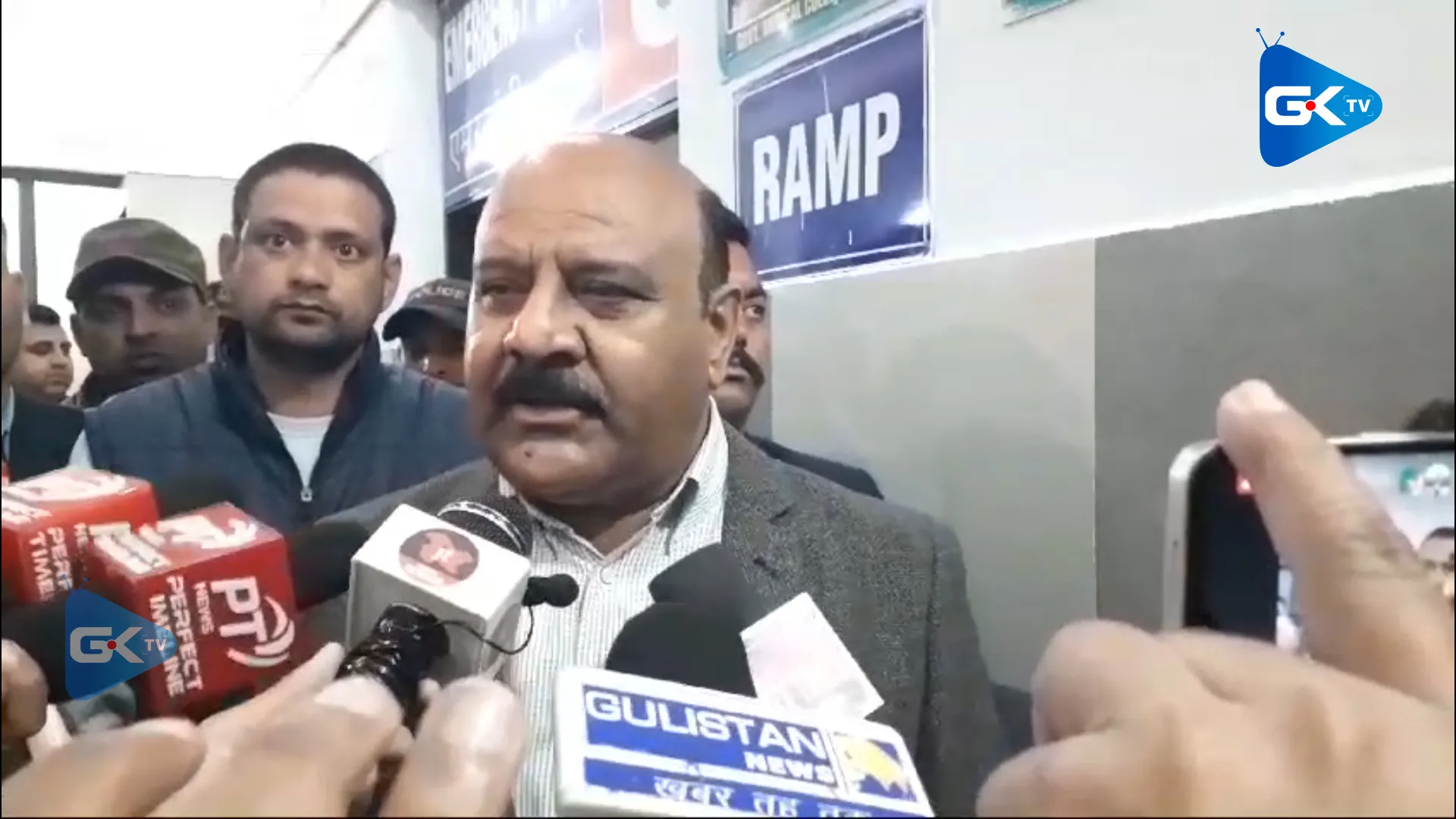

I thought my laptop had hung. These static but life-like frames are fairly common, throughout Kanawade’s film, about the death of father—and a gentle/subtle romance blooming in the ‘native’ Maharashtrian village, between grieving son, and his local friend (Suraaj Suman). It’s based on personal experiences of writer-director Kanawade, 38, whose dad used to be a chauffeur/driver, in —where Kanawade was born/raised, in a chawl, in the western suburb.

Sabar Bonda, his debut feature, premiered at the top, American, —first Marathi movie to do so—and picked up World Cinema Grand Jury Prize, to top that! Those static images in the film too come from life itself, as Kanawade tells me, over the phone from New York, shortly after celebrating his Sundance win. “I was trying to create the portrait of the time in my uncle’s village [for father’s funeral, in 2016]. There was only my mother and I, in one place; looking outside, doing nothing [for 10 days].

That silence and stillness had to be part of the film.” Those days are neatly punctuated in , with longish blackouts on the screen. First shot onwards, the film flows seamlessly, engagingly—from one scene into another, like a river of sorrow, kindness, care, humour.

.. It exhibits the sort of empathy we seek in our films, since we witness so little of it in the world around.

Sabar Bonda is a rare rural movie, about a gay couple—with neither the touch of activism nor ‘coming of age,’ as it were. It steers clear of the supposed shock-value of such a relationship ensuing in a conservative, sleepy hamlet. It’s about love.

As love should be. It’s foremost a lyrical ode to a father no more. Sabar Bonda means cactus pears, “that’s hard to eat, with cacti on its surface, but with juice/flesh inside,” serving as metaphor for the lives in the film.

As Kanawade puts it, cactus pears are a lot like dragon fruits, growing in the winters in Kharshinde, his mother’s village near Sangammer in Ahmednagar district, close to Shirdi. That’s where he shot the film, for its hilly terrain and artificial pond that Kanawade’s mother had helped build as a labourer during her teens. His father’s ancestral village is about half an hour away.

He says, “I couldn’t really mourn the loss of my dad there. Everyone just kept asking about my marriage. I was 30 then.

I began thinking of escape—what if I had a friend to sneak out with, for a while?” ‘What if’ is usually the starting point of most stories. So for Sabar Bonda. The top global gong for which is, indeed, a major feat for Marathi cinema, although not the first such.

Consider Chaitanya Tamhane’s The Disciple (2020), that was the first Indian film, over two decades, in the main competition section, at Venice Film Festival; winning critics’ award, plus Golden Oscella for Best Screenplay, no less. Tamhane’s Court (2014) was also a Venice award-winner. Or, Avinash Arun’s Killa (2014), that picked up Crystal Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival.

Off my head, these are formidable international titles by young filmmakers in Marathi cinema, that gets naturally eclipsed by Hindi movies, since Mumbai is the infrastructure-capital for both. “If you tell your stories in your tongue, they’re impactful; I hear mine in Marathi,” Kanawade tells me. “It was in Std X that I came across the Marathi textbook, [Annabhau Sathe’s] Smashanatil Sone, and I could visualise it cinematically.

” He continued writing/imagining stories that he decided to shoot as shorts, once the technology became easy/accessible. Some of which (U for Usha, Khidki) travelled to festivals. It was his father, who introduced Kanawade to movies at a young age—picking up tickets to single-screen cinemas, Navrang (Andheri West), Pinky (Andheri East), New Era (Malad West)—on his way to work.

These were, of course, mainstream pix. The grammar of Sabar Bonda is strikingly naturalistic, in line with the best of global art-house, I tell Kanawade. He says, “The story dictates the images, and you follow that vision.

I’d love to make popular movies, horror, dinosaurs...

The grammar will be different.” He was, however, subconsciously struck by films such as “[Jabbar Patel’s] Jait Re Jait (1977), movies of Shyam Benegal, Satyajit Ray, for how they weren’t like the others,” when they played on Doordarshan, growing up. One thing this debuting auteur shares with Ray is storyboarding.

Almost all of Sabar Bonda was first sketched by Kanawade, before he went to shoot. The filming-editing itself, like with most indies, involved several producers, starting with Neeraj Churi, “queer friends in London,” multiple film grants/funds, down to actor Jim Sarbh, to see it through, and eventually, make it to Sundance. Kanawade hopes people can catch it in theatres.

And that’s what Sabar Bonda is made for. Given its static images, landscapes, sound-design, subtlety in performances, I wish the same. The laptop won’t do.

.