by Nilantha Ilangamuwa When the Jaffar Express was hijacked by the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) this week, my mind immediately returned to an experience with a Baloch friend I met years ago in a far eastern country, where we were deeply engaged in human rights activities in Asia. His father had been abducted by Pakistani forces, an absence that had reshaped his entire life. He had been forced to take on responsibilities far beyond his years, caring for his mother and younger siblings while carrying the unshakable grief of uncertainty.

His mother, emaciated from years of waiting, still clung to the fading hope that one day her husband would return. “There is no life for a Baloch in Pakistan,” he had told me. “We are not just ignored.

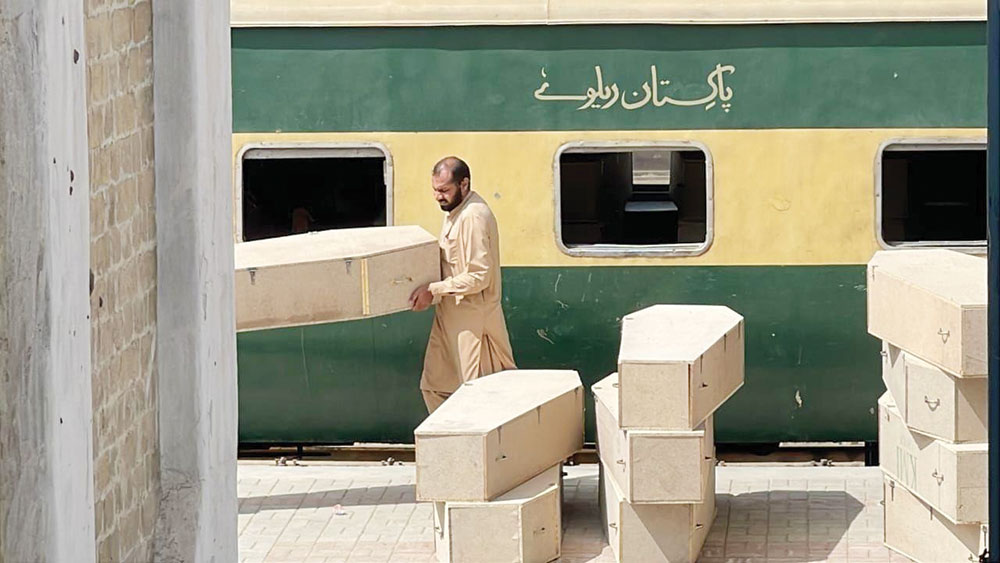

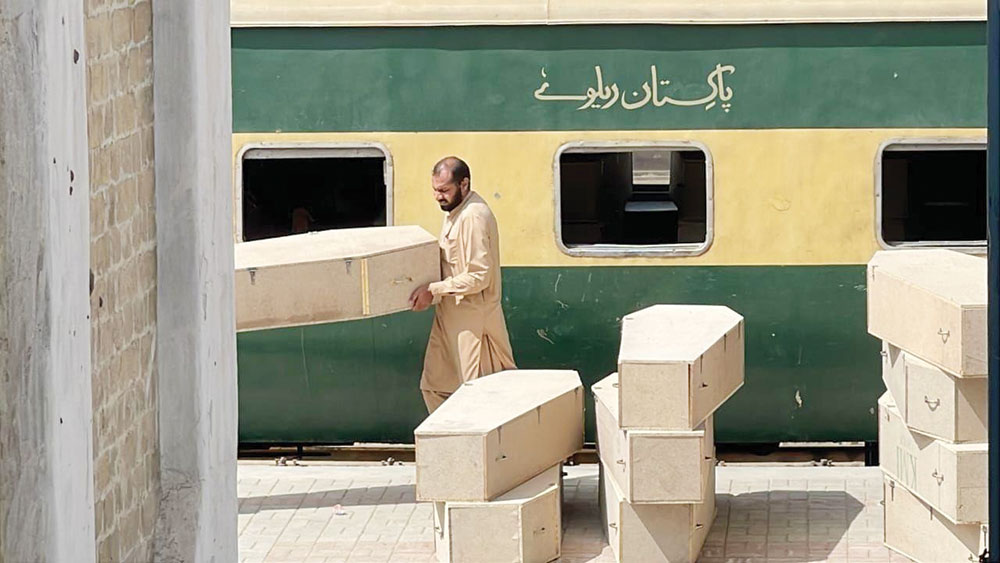

We are being erased.” The world remains indifferent. When the BLA stormed the Jaffar Express, taking hostages and issuing a warning to China and Pakistan, the reaction followed a predictable script.

There was outrage, condemnation, and a narrative of terrorism crafted to justify further military action in Balochistan. What was missing, as always, was the willingness to confront the deeper question: why does this violence persist? Why, 75 years after its forceful annexation, does Balochistan still find itself locked in armed conflict with the state that claims it? Violence does not emerge in a vacuum, nor does it sustain itself without a foundation. Those who decry acts of insurgency must also examine what forces compel the oppressed to consider violence as their last alternative.

Before Pakistan existed, Balochistan was an autonomous region governed by the Khan of Kalat. Its people were never consulted on whether they wished to join the newly created Pakistan, nor were they given a say in their own political destiny. When the British Empire carved up the subcontinent in 1947, the lines were drawn not with consideration for the inhabitants but with the arrogance of colonial bureaucracy.

Millions died in the partition, yet the demarcation was declared a success. The British, in their final act of imperial pragmatism, made choices not based on history, ethnicity, or governance, but on their own strategic interests. The CIA’s declassified assessments confirm that Balochistan was never meant to be independent in the eyes of its former rulers.

Its vast landmass, rich resources, and proximity to Soviet and Iranian borders made it a valuable asset in the emerging global power struggle. The Khan of Kalat declared independence on August 11, 1947, but by March 1948, Pakistani forces entered Kalat, and under coercion, the Khan was forced to sign the Instrument of Accession. The idea that Balochistan voluntarily became part of Pakistan is a myth sustained by decades of state propaganda.

The province’s integration was neither the result of democratic will nor constitutional process. It was secured through military pressure, diplomatic silence, and Western indifference. Since then, Balochistan has never been treated as an equal province of Pakistan but as a resource colony, a land to be extracted and controlled rather than governed.

Every rebellion, every demand for autonomy, and every call for justice has been met with violent suppression. The first armed Baloch resistance erupted in 1948 and was swiftly crushed. The second uprising in the 1950s was met with an even more brutal response.

The 1973–77 insurgency saw Iranian military support for Pakistan’s operations against Baloch rebels. Thousands were killed, and the leaders of the movement were exiled or executed. The pattern continued in the 2000s, where an increase in military operations, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings have turned Balochistan into one of the most militarized zones in Pakistan.

The world rarely takes note of what happens in Balochistan. The extrajudicial killings of Baloch activists, journalists, and students do not make international headlines. The mass graves discovered in desolate valleys, filled with the bodies of those who dared to demand rights, are not the subject of global outrage.

The routine abduction of Baloch men, who vanish into the machinery of Pakistan’s intelligence agencies, does not trouble the conscience of international powers. It is not because the suffering is lesser, but because it does not fit within the geopolitical interests of those who dictate which conflicts deserve attention. The Pakistani state has ensured that its grip over the province remains unchallenged by maintaining a dual strategy—economic exploitation and military repression.

Balochistan is Pakistan’s most resource-rich province. It supplies nearly 40% of the country’s natural gas, yet the majority of Baloch villages do not even have gas connections. The Sui gas fields, discovered in 1952, have powered Pakistani cities for decades while Baloch communities remain in darkness.

The Reko Diq mines hold some of the world’s largest reserves of gold and copper, yet the wealth extracted from Baloch soil does not benefit its people. According to a source in Balochistan, “Gwadar, a small fishing town that once sustained its inhabitants, has been transformed into a Chinese-controlled economic hub under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). “While Pakistani officials claim Gwadar will bring prosperity, the reality for local Baloch people has been displacement, loss of livelihood, and increased military presence.

” A source added, “Chinese investment has not been accompanied by local development. Instead, it has come with an escalation of military operations to suppress any opposition.” However, government narratives and mainstream media operating from Islamabad tell us the exact opposite.

The Baloch Liberation Army’s statement after the Jaffar Express hijacking was not just a justification for their attack—it was a declaration of intent. They warned China to leave Balochistan, stating that their fight is not just against Pakistan but against foreign forces profiting from their suffering. The BLA explicitly accused China of backing Pakistani military operations against Baloch civilians.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with their methods, their message is clear: they see China’s presence as an extension of the same historical injustice that has kept Balochistan in a state of subjugation. They do not distinguish between Pakistani and foreign exploitation. The Pakistani state’s response to the BLA and other Baloch separatist movements has followed the same formula—blame external forces, increase military operations, and continue policies of enforced disappearances.

Every time an insurgency erupts, Pakistan accuses Afghanistan and India of funding Baloch militants. The state refuses to acknowledge that the insurgency is not an external conspiracy but the result of its own decades-long policies of systematic marginalization. The military can kill rebels, but it cannot kill the cause.

The use of brute force has not extinguished the Baloch movement; it has only given it new recruits. Violence is never justifiable, but it must be understood. Those who condemn insurgent attacks must also acknowledge why these movements exist.

Balochistan was not a land of militants before 1948. It was not a place where people were willing to take up arms until every other avenue had been closed. Those who have spent generations demanding rights peacefully have been met with bullets, imprisonment, and exile.

When a people are denied agency over their own land, when their resources are stolen, when their voices are silenced, and when they are treated as an occupied population, they will resist. Some will resist through protest, some through politics, and others through the gun. The root cause of violence is not ideology but injustice.

The Baloch people do not seek war; they seek dignity, and until that dignity is restored, their resistance will not fade. The question is not whether Pakistan will defeat the insurgents. The question is whether Pakistan will ever confront the truth that the greatest threat to its rule over Balochistan is not the militants, but the very history it refuses to acknowledge.

.

Top

Jaffar Express Siege: The War Pakistan Can’t Hide

by Nilantha Ilangamuwa When the Jaffar Express was hijacked by the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) this week, my mind immediately returned to an experience with a Baloch friend I met years ago in a far eastern country, where we were deeply engaged in human rights activities in Asia. His father had been abducted by Pakistani [...]