In 1993, Jeffrey Seller was a 28-year-old theatrical booking agent who, with his business partner, Kevin McCollum, had an eye on a career as a producer. He’d become aware of the talented young composer Jonathan Larson, who’d already written one musical, Tick, Tick ..

. Boom! , and was now at work on another, Rent , a loose contemporary adaptation of Puccini’s La Bohème. But this was not a case of encountering a can’t-miss show and hiring a hall: Larson was green, the musical went through multiple versions before it cohered, and for a long time almost nobody (except maybe the composer himself) was sure it was going to work.

In this excerpt, adapted from Seller’s memoir, Theater Kid (out on May 6 from Simon & Schuster), the producer lays out the musical’s long road from dispiriting workshop to its simultaneously triumphant and tragic first preview performance. The office is busy. Kevin is raising money for a revival of Damn Yankees , which will get him producer billing on the poster and our agency the booking rights.

I’m booking four shows at once. The receptionist rings me. “Jonathan Larson on line one.

” Jonathan keeps in touch regularly, and I’m excited anytime he calls. Booking pays the bills while Jonathan promises the future. “Hello, friend,” I say.

“Guess what? I’m finally doing a reading of Rent .” Jonathan has transported Puccini’s penniless bohemians from Paris in the 1800s to the East Village in the ’90s where, of course, they can’t pay the “rent.” “Amazing.

” “It’s going to be at New York Theatre Workshop on June 10.” “I’m there.” “Just so you know, this is going to be the Hair of the ’90s.

” “From your mouth,” I say. It’s a pivotal moment in the theater industry. Kiss of the Spider Woman just beat Tommy for Best Musical, and the two shows tied for best score at the Tony Awards.

The business is seesawing between traditional music by guys like Kander and Ebb and contemporary music by guys like Pete Townshend. Jonathan wants to tip the balance. The day before the reading, Kevin brings a young producer wannabe named Peter Holmes à Court to the office.

I invite him to join me at the reading in the hopes that, if he likes it, we can get him to invest. We take the subway from Times Square to 8th Street and Broadway and walk to the Workshop. The auditorium has about 150 seats.

The stage is big for Off Broadway. Music stands are set up in front of 15 chairs, and there’s a band set up on the side. A group of actors take their seats.

They perform the opening number, “Rent.” It slams like a jolt of energy. The action shifts to a group of homeless people near Tompkins Square singing about life in Santa Fe, followed by two lesbians in a full-out argument.

As we move through the songs, the energy dwindles. I can’t latch on to any characters. I can’t find the plot.

This cycle of songs doesn’t electrify. It numbs. It feels like we’re lost in the East Village and can’t find a way out.

There’s no air-conditioning, and the theater gets hotter as the first act drones on, clocking in at over 90 minutes. Peter stands up at the intermission and says, “I’m sorry, I didn’t know it was this long, I have another appointment to attend.” He’s polite but his words belie his face, which signals loudly and clearly that he hates it and wants to get out of this hot theater as soon as possible.

The second act is no better. At the end of the show, my other guest, Rod, leans over and says, “Well, this show can’t be saved. I love Jonathan, but he should just work on something else.

” I’m deflated and a little bit embarrassed. Though there were good songs, they were untethered to any identifiable story. The cast never faltered, but their energy had no focus.

I didn’t walk away thinking about any of the characters. I had hoped Rent would be the answer — to musical theater, to my professional life. Instead, it felt like a mishmash.

When Jonathan calls me the next day, eager to hear my thoughts, I punt, and we make a date to have dinner. At Diane’s on Columbus and 72nd Street, we’re seated at a two-top near the front. There is space around us.

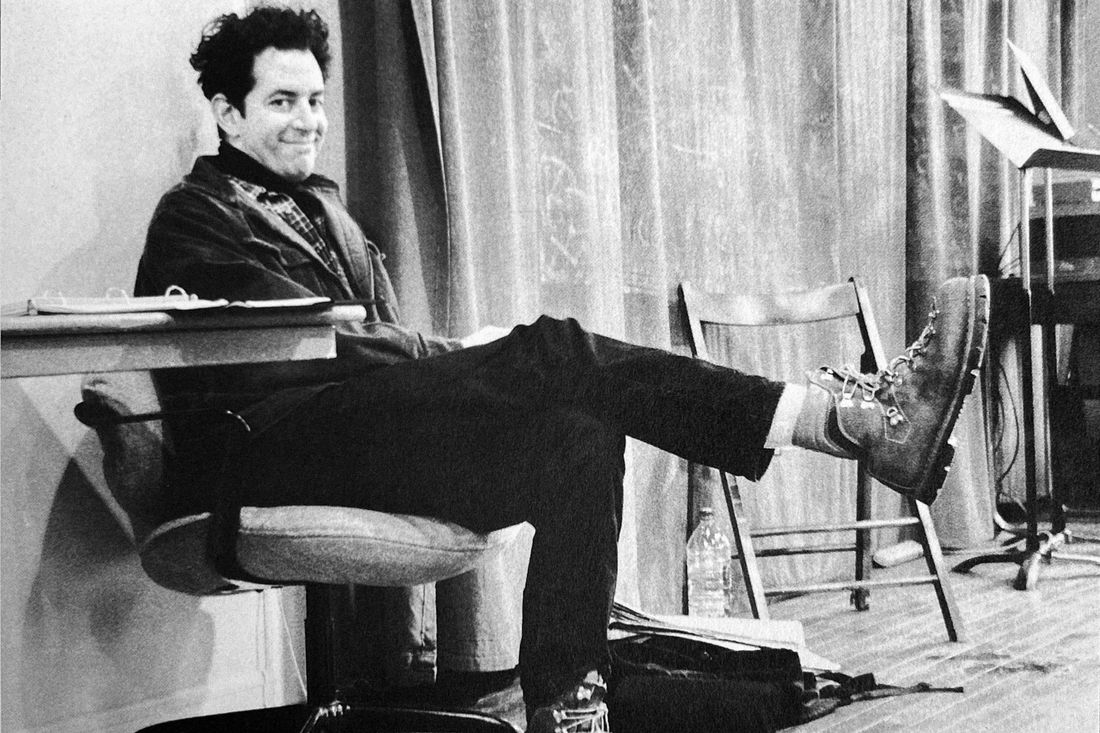

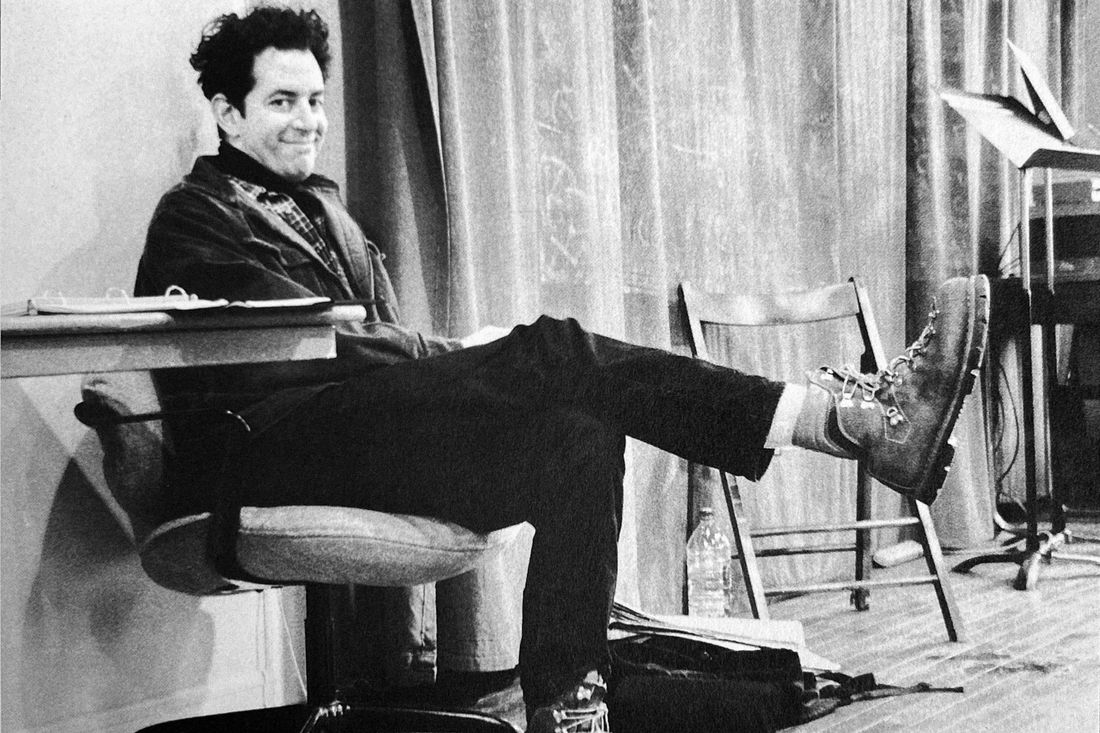

I feel like we’re all alone on a tiny island and that he’s going to cast me off it if I express what’s really on my mind. This is made worse by his needy eyes and floppy curly hair. His big ears stand up like a German shepherd’s.

“I’m all ears,” he says. No shit , I think to myself. I’m scared.

How do I be encouraging and still tell the truth? I’m afraid of hurting his feelings. I’m afraid that he’ll reject me and not want to be my friend anymore. “I love the songs,” I say.

“I love the location of the East Village. I love the grittiness of the opening number.” “That’s good,” he says.

“What else?” “But then I’m lost. It’s a presentation of songs that don’t seem to have anything to do with each other. No sooner do you establish the time and place with the opening song before jumping to a song about homeless people and Santa Fe.

I don’t get it. None of the characters are coming through.” Jonathan blinks.

“I’m not sure what you’re trying to do. Are you just trying to compose a collage of life in the East Village?” Jonathan’s ears turn red, his eyes turn down, his shoulders hunch — I’ve bruised him. “I’m not writing a collage,” he says.

“Then you need to tell the story of La Bohème . I need to understand the beginning, middle, and end. I need to be able to follow Roger and Mimi.

” “I’m going to do this,” he says. “You’ll see.” “Good, because if you don’t do this, I think I’m going to have to leave this business.

” “You’ll be taking me with you,” he adds. A year and a half later, in the fall of 1994, Jonathan wins an award from the Richard Rodgers Foundation to pay for another workshop at New York Theatre Workshop. James Nicola, the artistic director of NYTW, recruits rising director Michael Greif, whose career has taken off after directing an acclaimed production of Machinal at the Public Theater.

Michael’s raw, urban, industrial aesthetic, combined with searing honesty, is exactly what Jonathan wants for Rent . My excitement leaps when Jonathan invites me. Despite my previous criticism, I am hopeful that he has cracked this musical.

I tell Kevin and he’s happy to join me. We take two seats in the first row. The house is about half-full.

Stephen Sondheim makes his way down the aisle and sits two rows behind us. I try not to gawk. He pulls out a newfangled device, the Apple Newton, on which to take notes.

Right before it starts, I feel the need to manage Kevin’s expectations, particularly after the reading with Peter Holmes à Court. “Look, this is either going to be brilliant or a piece of shit,” I say. “It’s going to be brilliant,” he replies, “I can feel it.

” “We’ll see.” My heart beats faster. That was what I thought the last time I saw this.

Two young guys take the stage. One is blond, hair almost white, wears wire glasses, and exudes the presence of a bohemian intellectual. The program says his name is Anthony Rapp.

I remember him as one of the teens in Six Degrees of Separation . The other guy, with long brown hair and a deep voice, is thick, trapezoidal, but he’s not flabby. They sing the opening song, “Rent,” which is as dynamic as I remember it from 18 months ago.

Then a young Latina woman — small, sexy, with overflowing brown hair and a curvy catlike face — sings a rock song called “Out Tonight.” Her name is Daphne Rubin-Vega and her deep voice growls with gravel and gold. She’s Mimi.

She sings like a boxer in a ring using her voice to knock out her opponent. A drag queen visits Mark and Roger’s loft and sings another high-spirited, flashy number describing how he recently earned a bunch of money. Though the plot isn’t yet discernible, these downtown bohemians express themselves in vivid, riveting ways.

After the introduction of two lesbians, who sing another fun song, Roger has the space to himself where he tries to access his creativity, to summon inspiration, and start composing again through a song called “Right Brain.” He has a dark, rumbling rock voice that shares one trait with Daphne — it’s nothing like the sounds that emanate from the current Broadway voices. The story cracks open when Mimi knocks on the door and meets Roger.

They court each other in the most ingenious rock duet I’ve ever heard, “Light My Candle.” It’s flirtatious, it’s catchy, and it perfectly sets in motion the love story of this piece. The sound of this show pricks my ears in a whole new way — it’s like nothing I’ve ever heard before.

Kevin and I look at each other with the same expression: Holy fuck . Kevin whispers, “That’s the best musical storytelling I’ve ever seen.” Inspiration and brilliance are on this stage.

It is messy, but that’s a problem for another day. With “Light My Candle,” Rent is declaring itself. The musical unfolds with power and ingenuity.

The woman playing Maureen sings a performance piece in the style of Laurie Anderson while accompanying herself on the cello. At one point she picks the cello up and frames her head with it. It’s zany and surprising.

Act One ends in the Life Café with a rousing number about Bohemia called “La Vie Bohème.” After the blackout, Kevin turns to me. “Get out the checkbook,” he says.

“Are you joking?” “We have to do this show.” After the unfortunate first reading, I’m relieved. “Slow down, just let me introduce you.

” We walk up the side aisle. Jonathan greets us, eager to hear our reaction. “You’ve found the story,” I say.

“Told ya.” “This is my partner, Kevin, I was telling you about.” “Hey, thanks for coming,” says Jonathan.

“No, thank you ,” says Kevin. “This is, like, one of the best musicals I’ve ever seen.” Jonathan is like a puppy about to receive the best treat ever.

“Really?” “We have to do this with you. What do you need?” Kevin takes out his checkbook, which kind of embarrasses me, then continues, “What do you want? We just want to help you get this on.” “Don’t you want to see the second act first?” asks Jonathan.

“I already know it’s great. This show must be seen,” says Kevin. By the end of the show, after Mimi comes back to life, Kevin’s mission becomes an obsession.

“Seriously, what do you want?” he asks Jonathan. “Well, if you’re offering, I need to make a recording of this workshop before everyone goes away.” “Done,” says Kevin.

“No problem.” He can’t stop talking on the subway ride home. “This is going to be huge,” he says.

Jonathan introduces us to Michael Greif. Clad in jeans, tennis shoes, and a baggy black sweater, he has a face that’s defined by the kind of round glasses that Harry Potter, still in the imagination of J. K.

Rowling, will popularize in another two years. Michael is intimidating and cool. He talks with a trace of sarcasm.

When he says, “Nice to meet you,” I’m not sure he means it. That he is the perfect director for this show is proven by this workshop. The audience is vocal, their cheers are hearty, and the smile on Jonathan’s face is brighter than any I’ve ever seen.

The Sunday before Thanksgiving, Jonathan and the cast go into a recording studio and make a high-quality cassette of all the songs. At a cost of $8,000, it becomes the definitive record of this workshop and the soundtrack of our lives. Kevin listens nonstop.

I am enthusiastic but cautious. Jonathan keeps saying, “This is going to be the Hair of the ’90s.” I tell him not to say that out loud.

In the summer of 1995, Jonathan goes away to work with a dramaturge on the book, music, and lyrics. In October, we do a small reading of a revised script on the fourth floor of the new Workshop annex. The only attendees are the production team and a few staff members of the Workshop.

Kevin is out of town that night. The story is now framed by Angel’s funeral, with the narrative unfolding as a series of flashbacks seen through Mark’s lens. The first half-hour is so full of information about every character that it’s impossible to latch on to the arc of the story.

No one is in focus. Mimi seesaws between hopeless heroin addict and righteous truth-teller. As the sing-through proceeds, everyone in the room slowly sinks into their chairs.

The show has gone backward. There are a few winning new songs: “Happy New Year,” which kick-starts Act Two, when the group breaks back into their building after Benny has locked them out; “Tango Maureen,” a witty metaphor for Mark and Maureen’s relationship written in a traditional musical-theater style; and “What You Own,” a rock duet for Mark and Roger, which is the “11 o’clock” number. Great tune, great hook.

I question whether the story can hold another political theme, “We are what we own,” at this late stage of the evening, but recognize that the song provides an electric jolt that will help catapult us to the finale. A couple new songs are not good, especially “Your Eyes,” the song Roger sings to dying Mimi. The lyrics are generic (“Your eyes, as we said our good-byes .

.. took me by surprise”), the melody flaccid.

That it’s the song Roger has been working on all year makes it lamer. It can’t be the final number. I compose a three-page letter to Jim Nicola, detailing my concerns.

I conclude with the following: Rent is still in search of a skeleton that holds it together. There is still no central story. It’s there and we all know it: It’s Roger and Mimi.

But it seems as if Jonathan, in the spirit of equality and community, and in his desire to express many of his sociopolitical views, is giving equal time to everything. This new version of La Bohème is three times more complicated than the original and sometimes incoherent. It must be simplified.

It must be clear. I’m not trying to sound dire, and I don’t think there’s a crisis here. I think the piece is begging for heavy editing .

.. It demands dramatic discipline.

Jim and Michael Greif talk. Jim seriously considers postponing the production. Michael, who recently became the artistic director of La Jolla Playhouse, can’t change his schedule, which would mean postponing for a full year or getting a new director.

Jonathan, who has already given notice at the Moondance Diner, is infuriated and scared. His chance to finally get a show on is about to slip away. I call Manny Azenberg, the rabbi of Broadway, and ask for advice.

“Don’t start unless you’re sure the script is ready,” he says. “You have no idea what you’re going to discover when you put it in front of an audience, but if you’re not absolutely certain it’s in the best possible shape before you start, you’ll never catch up.” “I think Jonathan will explode if we postpone for a year.

” “It’s better than a flop,” he says. “Remember, if you have two or three weeks of previews, it’s nothing. There’s very little time to make changes when you’re performing every night.

” Manny’s advice is tough to absorb. Postponing feels impossible and going ahead feels foolhardy. Jim gives my notes to Jonathan.

He calls and invites me to dinner. “Your notes stung,” he says. “They made me really defensive, like ‘What the fuck do you know?’ Then I called Sondheim, and he told me that if I want to work in this business, I have to collaborate.

Or at least listen. So I read them again.” “You’re right,” I say.

“None of us know what we’re doing. We’re all new at this.” “I’m going to get this right,” he says.

“I believe you.” “I know it’s too complicated,” he says. “I’ll make the beginning clearer.

And I know what you’re saying about Mimi.” “That’s good,” I say. “But ‘What You Own’ is a fucking great song and I’m not cutting it.

” “Fair,” I respond. “Let me drive you home,” he says. He recently bought a beat-up old green station wagon.

“This is Rusty,” he says. “Three hundred bucks! I figure, if the show doesn’t work out, I can get the fuck out of here and drive to Santa Fe.” “Touché!” “Good rhyme,” he says.

I go to sleep hopeful, once again, that this show might finally come together. A snowstorm blankets New York the day of the first rehearsal. It’s mostly a day of orientation; everyone introduces themselves in a warm but tentative way.

In the adjacent kitchen, I meet the set designer, a small, skinny man named Paul Clay, who is working the nerdy hipster vibe better than anyone I’ve ever met. Paul is a visual artist and sculptor who lives in the East Village. He’s like a character in Rent .

He shows us his drawing of the set, which is a big sculpture of junk held aloft by scaffolding. It feels less like a fleshed-out design and more like a few scribbles on the page, but this show is different. The actors learn the score and Michael starts staging scenes and dances over the holidays.

I return on January 2, 1996, for the first sing-through of the show. Adam is wearing denim overalls — he looks more like Pippin than Kurt Cobain. He never looks up from his music stand.

But that doesn’t even matter. His voice soars with a muscularity that’s thrilling. When he lets it rip during his first song, “One Song Glory,” a new lyric set to the tune of “Right Brain,” I get goose bumps down my back.

At this straightforward sing-through, as each actor sings and reads from their scripts, the show makes sense for the first time. Every scene is like a building block placed intentionally over the one below it. Act Two is even better.

The first act, which dramatized Christmas Eve, leads to a second act that starts on New Year’s Eve, then follows the next year through the seasons and holidays: Valentine’s Day, spring, Halloween, then a return to Christmas Eve one year later. I’m still not crazy about the last song, “Your Eyes,” but I’ll harp on that another day. At the end of the show, I’m satisfied and relieved.

Jonathan has solved the “math” of the plot — it all adds up — which makes the songs more rewarding and the characters more engaging. I realize I’m not viscerally moved at the end. After all this analysis, criticism, and change, I know the magic trick: I know how the magician cuts the woman in two.

“You did it,” I tell Jonathan after the sing-through. “It works, it makes sense.” He smiles with pride.

He knows it as well. “I have one more song to write. It’s for Maureen and Joanne in the second act.

” “I can’t wait,” I say. On this first workday of the year, I walk out into another snowstorm feeling optimistic. During tech, Jonathan gets sick with a stomach bug and goes to Cabrini Medical Center.

They examine him and determine that he had food poisoning. I touch base with Jim, who also tells me things are progressing well, except that Jonathan felt sick to his stomach again two days later and went to St. Vincent’s Hospital, where they examined him and sent him home to rest.

“Why didn’t he go to his doctor?” I ask. “He doesn’t have a doctor,” says Jim. “He doesn’t have a fucking doctor?” “He doesn’t even have health insurance.

” This news stings, sending me back to college when I didn’t have health insurance and constantly worried about getting sick. The dress rehearsal is on January 24, a Wednesday. When I walk into the theater, it’s already filled with 199 people and the air is thick with anticipation.

I’m by myself because Kevin is away. The stage is organized clutter, like an abandoned lot in the East Village. There are two metal tables with red chairs arrayed around them, and a scaffold sculpture of East Village detritus is up left forming a Christmas tree.

The brick back wall is painted blue. Most prominent is a thick yellow extension cord that runs from the center to off stage left. The band is under a platform stage right.

Three standing mics on either side of the stage apron indicate that this will be a hybrid between a musical and a rock concert. The set is raw and beautiful at the same time. Its minimalism is jarring at first, then its parts come into focus.

With attention to texture and color for accent and buoyancy, Michael and his designer have created an evocative environment for this story to play out in. The show is electric, the cast is on fire. Daphne and Adam are fierce.

Wilson Jermaine Heredia, who plays Angel, is adorable and feisty, a strong young man and a sexy drag queen. The duet, “I’ll Cover You,” that he sings with Collins, the warm and buttery Jesse Martin, is glorious. “La Vie Bohème,” the finale of Act One, is dinner party, dance, and rave, all in one.

The Act Two opening, “Seasons of Love,” is rapturous, and Jonathan’s new song for Maureen and Joanne, “Take Me or Leave Me,” stops the show. Michael’s staging of “Contact,” a song dramatizing the ups and downs of every couple having sex, which evolves into Angel’s death, is riveting. Angel’s funeral is sad, powerful, and earned.

At the end of the run-through the audience whoops and hollers, clapping, whistling, and stomping their feet. Granted, these are friends and family — not a real audience — but it still feels good. I approach Jonathan after the show and tell him how great the show is.

He smiles a little, as if to say, I told you so , but also with some pain on his face. He’s a bit distant. “I’ve been kind of sick,” he says.

“I’m sure it’s stress-related.” “Are you going right home to sleep?” “Right after my interview with the Times ,” he says. Our publicist persuaded the New York Times to do an article on the hundredth anniversary of La Bohème and its staying power as reflected by Rent .

“Feel good, my friend. It’s going to be great.” I offer up some compliments to Michael after the performance, and he thanks me with his customary coolness.

“Wilson is spectacular as Angel,” I say. “Yeah. I was thinking about firing him.

” “Not now, I hope,” I say. “He came a long way tonight,” says Michael. I’m pleased by his steady focus and the fantastic world of the play he has created.

Exiting the auditorium, I see Jonathan sitting behind the window of the box office talking to Anthony Tommasini, the chief music critic of the Times . I walk to Third Avenue and call Kevin, who’s returning from a business trip, and report on the evening. He’s thrilled.

“I’m glad you’re back,” I say. “I have one more thing to tell you,” he says. “What?” I ask.

“This is going to be huge,” he says. This time, I enjoy it, and respond, “From your mouth.” I wake up on Thursday filled with anticipation for the first preview.

I spend more time than usual picking out my outfit, then walk through the Great Lawn, covered in snow and midway through a reconstruction, to my therapist’s office, I think about Tick, Tick ...

Boom! and Jonathan’s song “Louder Than Words,” which transpires on the ground I’m traversing. “Tonight is the first preview,” I tell Dr. Fine.

“I’m excited, I’m nervous, I have no idea what’s about to happen. I just hope Jonathan isn’t mad at me.” “What do you mean?” “He wasn’t his usual self last night,” I say.

“He was a little bit absent.” I talk and talk, and when she says, “We’re done for today,” I get up, put on my coat, and get on the subway to Times Square. At the office, I bound up the escalator, eager to start the workday.

When I enter, the receptionist is looking down. Silence. I walk by two more employees, both looking away from me.

As I pass the office of John, our contract manager, he stops me. “Jeffrey, I have something to tell you,” he says. He looks serious.

I stand in the doorway of his office, my coat still on. “What’s up?” I ask. “I don’t know how to say this.

” “What?” I ask. “Jonathan Larson died last night.” Blood drains from my head.

I fall against the frame of the door. “Jay Harris called this morning to let you know.” “What?” I feel like I’m falling backward.

“I’m so sorry to be the one to have to tell you this. He collapsed after he came home from dress rehearsal. His roommate found him on the kitchen floor.

” That night, the theater is somber. No one talks in the lobby. It’s hard to absorb that this is the same place in which Jonathan watched an audience go crazy for his show at dress rehearsal last night.

Tonight it hosts his memorial service. We take seats in the second row. Another downtown producer, Anne Hamburger, sits next to me.

Jonathan’s best friends, Jonathan Burkhart and Eddie Rosenstein, walk onstage. Their eyes are red. Holding back tears, Eddie says, “This show was the most important thing in Jonathan’s life.

” “We’re not supposed to be here right now, Jonathan is supposed to be here,” says Jonathan Burkhart, rubbing his eyes and nose. “The only way we could think of to honor Jonathan right now is to do the show. So the actors are going to sing it but not do the staging.

They’re also in shock and we don’t want anyone to get hurt,” says Eddie. The actors, led by Anthony Rapp, enter to a silent audience. They sit in the red folding chairs around the two metal tables with their street clothes and head mics.

The show starts gently. When Adam starts singing, “One song, glory, one song before I go,” we all start crying. It’s as if Jonathan was writing his own life and death.

With each song, the actors commit a little more fully to the moment. When we reach “La Vie Bohème” and Collins announces, “Mimi Marquez, clad only in bubble wrap,” Daphne leaps out of her seat and jumps onto the table dancing. Then Wilson joins.

Within seconds, the entire cast is doing the full choreography of “La Vie Bohème,” and what started as a reading has blossomed into a full-out performance. The power of Jonathan’s words and music take over the theater. The first act finishes with an ovation bigger than at dress rehearsal.

A man I don’t know approaches me. “Are you involved with this show?” he asks. “Yes,” I reply.

“I love these people. I just want to hang out with them.” I’m pleased that, even under these circumstances, he’s connecting to the show.

Kevin and I get up to meet Jonathan’s parents, Al and Nan. I’m frightened. I don’t know what to say or how to encounter the pain they must be feeling.

We shake hands. We offer our condolences. “He believed in you guys,” says Al.

“Talked about you all the time.” “Please. We just want you to do the show,” says Nan.

“That’s right,” says Al. “You have to do the show.” “We won’t let you down,” says Kevin.

“We loved your son, and we love his show,” I say. The beauty and pain of “Seasons of Love” kicks off Act Two. The cast performs full-out.

The “I’ll Cover You” reprise, written as Angel’s funeral, is about Jonathan tonight. For me, it will always be about Jonathan. When Adam and Anthony sing, “We’re dying in America at the end of the millennium,” the prescience is searing.

If, indeed, we are what we own, then Jonathan is Rent . At the end of the performance, there is extended applause and the cast exits. Silence.

No one moves, no one says anything. The woman sitting next to me takes my hand. Anthony emerges from the door upstage center and sits down at the table.

The other actors return and sit down. We are one community sharing grief. No one knows what to do next.

“Thank you, Jonathan Larson,” I say out loud. There is a long, powerful applause. We file out of the theater quietly and go home with the hope that the show that starts previews tomorrow night will honor Jonathan’s vision.

Copyright © 2025 by Jeffrey Seller. From the forthcoming book Theater Kid: A Broadway Memoir by Jeffrey Seller, to be published by Simon & Schuster, LLC. Printed by permission.

.

Entertainment

“It Feels Like We’re Lost in the East Village and Can’t Find a Way Out”

Jeffrey Seller, co-producer of ‘Rent,’ on Jonathan Larson and his show’s bumpy road to success.