The Utah Legislature became the first two-time winner of the Society of Professional Journalists’ national Black Hole Award , awarded annually to the government entity that gulps up sunshine and blots out transparency. Utah locked up the “dishonor,” according to SPJ, for bills that dismantle the state’s records committee , make it virtually impossible for the public to recoup legal fees when records are improperly withheld, obscure college president searches and axe language recognizing the public’s constitutional right to access information about how their government operates. “I think it’s best for the state.

I think it’s best for state government. I think it’s best for the people,” Gov. Spencer Cox said during his monthly news conference earlier this month.

He later signed each of the bills into law. The Legislature was given the dubious distinction in 2011, the first year the award was handed out, for dismantling much of the state’s open records law in the last days of that year’s legislative session. Amid massive public outcry, then-Gov.

Gary Herbert called the Legislature into special session to repeal the law , and a working group of various stakeholders was set up to discuss reforms to the law, most of which were left intact. Jeff Hunt, an attorney who helped craft Utah’s open records law — the Government Records Access and Management Act, or GRAMA — in 1991, said the Legislature continued to erode government transparency and the public’s access to information this year. “We’re always playing defense,” said Hunt.

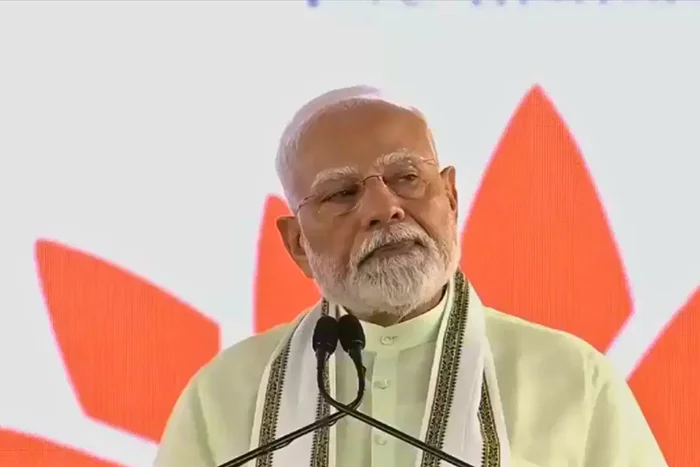

“I’d say in the last five to eight years there has been an accumulation of bills to really chip away at GRAMA.” (Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune) Sen. Michael McKell, R-Spanish Fork, and Sen.

Calvin Musselman, R-West Haven, at the Utah Capitol in Salt Lake City on Thursday, March 6, 2025. It includes keeping the public from accessing state officials’ calendars , email addresses of candidates for office, information gathered by a water strategy commission , school voucher information, contracts showing how much college athletes are paid for endorsement deals, interviews done with police officers involved in shootings, among others. “When GRAMA was enacted, we were probably in the top 20% of states that had the best open records laws,” Hunt said, “and now I think we’re definitely more on life support when it comes to GRAMA.

It’s just not the same robust statute.” Here is a look at some of the changes made to Utah’s transparency laws this legislative session: ‘Good, fast or cheap’ The Utah State Records Committee will meet for the last time on April 17. Since 1992, the seven-member board has ruled on appeals by hundreds of Utah citizens and journalists who have been denied access to public records.

But this session, the Legislature passed SB277, sponsored by Senate Majority Assistant Whip Mike McKell, R-Spanish Fork, that will dissolve the committee and hand the power to decide records disputes to an administrative law judge appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Senate. McKell said the records committee was taking too long to resolve appeals — 156 days, on average, in 2023 — and he believes a law-trained judge can move through cases more efficiently. He also said a judge with legal training will produce rulings soundly rooted in the law.

However, the district court upholds 98% of the records committee’s appealed decisions. “I think you’re going to see a scenario where we go from 156 days on appeals to most cases won’t need an appeal, but that timeframe is going to be drastically shortened,” McKell said. “I think overall it’s just better efficiency for the public.

” “When I spike the ball two years from now, nobody will care because GRAMA will be fixed,” the senator added. Originally, McKell’s bill also would have eliminated the “Balancing Test” — which allows the records committee or courts to make information public, even if it normally would not be, if there is a clear public benefit to letting the records see the light of day. That provision met with overwhelming backlash from members of the public and McKell agreed to leave it in place.

Hunt said saving the balancing test was a lone bright spot this session when it comes to government transparency. So, what should Utahns expect with the new appeals structure? Much of that will depend on who is chosen for the spot, according to Mitch McKenney, a professor of media and journalism at Kent State University. “There is so much riding on that person’s posture,” he said.

McKenney has studied the appeals processes in Ohio, Pennsylvania and Connecticut, and said each of them has strengths and weaknesses. Ohio requires parties to try mediation, which resolves half of the cases before going to a judge. McKenney said the appeals that do get argued are typically resolved fairly quickly, with the requester getting some or all of the documents roughly 60% of the time.

The appellee has to pay some fees for the appeal and document costs. Pennsylvania handles a slew of cases — 3,400 last year — but rejects the bulk of them on procedural grounds. The success rate of someone appealing a case in Pennsylvania, McKenney said, is in the 30% range.

Connecticut has a board that adjudicates appeals, and generally, its rulings favor public access, but there is a backlog, and it can take time to resolve disputes. “My shorthand is: Good, fast or cheap — pick any two,” McKenney said in an interview. While McKell’s motivation for disbanding the records committee is speed, setting up the new system could also lead to delays.

The records committee’s penultimate meeting Thursday included 13 cases on the agenda, leaving around 70 more outstanding, a representative for the committee said. Some of those cases have been outstanding for several months. Any cases held over after next month’s final meeting will be handed off to the incoming administrative law judge.

When that individual will be on the job is unclear, however. Funding for the position won’t be available until July. A spokesperson for the Utah Senate said the position could be covered within the existing State Archives budget, but that the Senate may not be able to confirm the appointee until mid-June.

(Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune) Sen. Calvin Musselman, R-West Haven, at the Utah Capitol in Salt Lake City on Thursday, March 6, 2025. Paying for transparency Last year, after a judge ruled against then- Attorney General Sean Reyes’ attempt to keep his official calendars private , taxpayers had to pay more than $132,000 to cover the legal fees for the attorneys who represented KSL.

Previously, fees have been awarded in cases where courts ruled that government entities improperly denied records related to government corruption cases, police shootings, taxpayer-funded lobbying payments and sexual harassment by public employees. Rachel Terry, the head of Utah’s Division of Risk Management, said during the legislative session that those sorts of cases are posing increasing costs to the state. The easy solution, said Hunt, would be to first, follow the law and not refuse access the public has a right to have and, second, to train records officials to know what the law is so they don’t end up losing in court.

Instead, senators tacked on a provision to a bill that already passed the House that lets the state off the hook on legal fees unless the denial of the requested records is objectively without merit. Sen. Calvin Musselman, R-West Haven, said the language he added to HB69 levels the playing field because it applies the same standard for awarding legal fees to the party requesting the records and the government entity denying them.

The bill passed with a total of seven minutes of discussion and no public input , and Cox signed the bill into law earlier this week. Hunt said making requesters bear the full cost of legal challenges — even when the government improperly denied access — is going to be too big of a burden on media outlets and even more so on regular citizens. “Those cases aren’t even going to get brought anymore,” he said.

“It’s going to make the government act like an unscrupulous insurance company. Just deny, deny, deny until you have to go to court, and the requester isn’t going to be able to afford to go to court.” (Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune) Rep.

Jordan Teuscher, R-South Jordan, during the 2025 legislative session, Wednesday February. 26, 2025. More than a “clean-up” When the 1991 Legislature passed GRAMA, it opened with a clear statement that the Legislature intended to “promote the public’s right of easy and reasonable access” to records, specify conditions where access could be restricted, “prevent abuse of confidentiality by governmental entities,” set guidelines for weighing competing interests, and to “favor public access when .

.. countervailing interests are of equal weight.

” A bill sponsored by South Jordan Republican Rep. Jordan Teuscher, R-South Jordan, HB394, will chop that language from the law. Teuscher said the measure was a “clean-up” bill to remove legally nonbinding intent language from 34 sections of the state code.

The idea, he said, is that laws should do what they’re intended, meaning such intent language is superfluous. The language in 25 of the 34 sections barely changed. Only the words “The Legislature intends .

..” or similar phrases were removed, leaving the Legislature’s statement of the actual intent of the law in place.

But in nine sections — including those relating to the State Ethics Act, opioid treatment, public assistance, workplace safety and GRAMA — the intent language was deleted entirely. West Valley City Sen. Daniel Thatcher said he did not view eliminating the Legislature’s intent as it related to GRAMA as a simple clean-up.

“I don’t believe that is a technical correction. I believe that is a significant policy decision and I’m not comfortable voting to strike that language recognizing the right of the public to know what we’re doing,” he said. Secretive hiring University presidents are some of the state’s highest-paid employees and traditionally, as a new president is selected, the public has been able to find out the three finalists for the job.

That will change, now that Cox has signed SB282. Sponsored by Logan Republican Sen. Chris Wilson, it would only allow one finalist’s name to be released before a final vote to approve the appointment.

Wilson said publicly releasing other contenders’ names might complicate a candidate’s current job and make it less likely that top-tier talent would seek the post. The Utah Media Coalition opposed the bill, arguing that in such high-profile public positions, the finalists should be public so they can be thoroughly vetted before one of them gets the job. That system has worked well for Utah, the coalition argued, and changing it just makes the process more secretive.

.