The military crackdown in Chhattisgarh ’s Bastar region, the heartland of Naxal insurgency, has significantly weakened the decades-old movement, yielding tangible and immediate gains for the Indian state. As the March 31, 2026, deadline looms over security forces to eliminate Naxal insurgency, Ajai Sahni, the executive director of the Institute for Conflict Management and South Asia Terrorism Portal and editor of South Asia Intelligence Review , argues that the Modi government should pursue political engagement with Maoist insurgents, who have ceased to be a national threat. Sahni suggests that, given the dominant position of government forces, the emphasis should shift from their complete annihilation towards reconciliation.

In this interview with Frontline , he further explains that the decline in Naxal insurgency owes to the sustained consolidation of the security apparatus over the past two decades, rather than any bold new strategy. The current government, he says, has merely pursued the existing policy by making “ruthlessness” more explicit and this could have its own consequences. Excerpts: How realistic is the government’s March 2026 deadline to eliminate Naxal insurgency, considering the current state of operations? This deadline-driven approach is strategically flawed as it creates unsustainable pressure on security forces to overreact.

Recent patterns show a rising trend of large-scale killings of so-called Maoists, often without confirming their actual roles. Over the past three years, many Maoists have been killed with minimal security force casualties, suggesting an implicit policy of annihilation. Given that Maoist influence has significantly declined since its peak in 2008–2011, it is time for the state to adopt a more open and conciliatory stance.

The Vajpayee government and even the Modi government in 2016 offered unilateral ceasefire against Islamist militants during Ramzan in Kashmir. But the approach appears to be altogether different when it comes to Naxalites..

. The government has reached settlements with several insurgent groups in the northeast , including in Nagaland, Assam, Manipur, and Tripura. In September last year, the government signed a settlement with the National Liberation Front of Tripura and the All Tripura Tiger Force.

Given that Maoists are now largely cornered and neutralised, a similar approach should be considered. An honourable exit should be offered instead of resorting to further bloodshed. The state can afford to be generous, recognising that these are ultimately its own people.

If they refuse, further action can be taken as needed. Additionally, operations must be strictly monitored to prevent unnecessary killings. Also Read | Prioritise a timeline to eliminate poverty and exploitation: Ramesh Badranna During the UPA [United Progressive Alliance] government, was there ever a serious consideration of deploying the Army to combat Maoist insurgents? The Army should only be deployed in insurgencies when the state’s administration and police collapse, and even then, only briefly.

In India, however, emergency deployments often become permanent. When P. Chidambaram was Union Home Minister, there was talk of deploying not just the Army but also the air force, reflecting a hasty and ill-conceived strategy.

India’s counter-insurgency approach has traditionally relied on minimal, proportionate force, avoiding the large-scale destruction seen in global conflicts. The idea of Army deployment was a knee-jerk reaction rather than a well-thought-out strategic decision. From a security perspective, how is success defined against an armed insurgency? In the past, since the Naxalbari movement, we have seen many such crackdowns on Maoist insurgents.

There is no single, legitimate, or definitive parameter for assessment; a broad evaluation across multiple factors is required. This includes counter-insurgency operations, fatalities, areas under insurgents’ influence, and operational reach. Over-emphasising any one factor distorts strategy.

A comprehensive assessment also considers elements such as bandh calls, propaganda activities, and poster campaigns in their areas of influence. A Gutti Koya tribal family in an Internally Displaced Family (IDP) settlement, migrated from Chattisgarh State, in Chintoor agency in East Godavari district, Andhra Pradesh. | Photo Credit: T.

APPALA NAIDU In your considered opinion, what is the approach of the current government? The current government appears to focus primarily on fatalities as the key marker, which is a flawed approach. This approach is problematic as it incentivises security forces to maximise kill counts. While repression may appear effective, it fosters deep resentment that can manifest in new forms.

Eliminating Maoists alone won’t ensure stability if widespread anger persists. Governance—whether in a democracy or dictatorship—relies on legitimacy, not just force. Without legitimacy, no government can sustain itself.

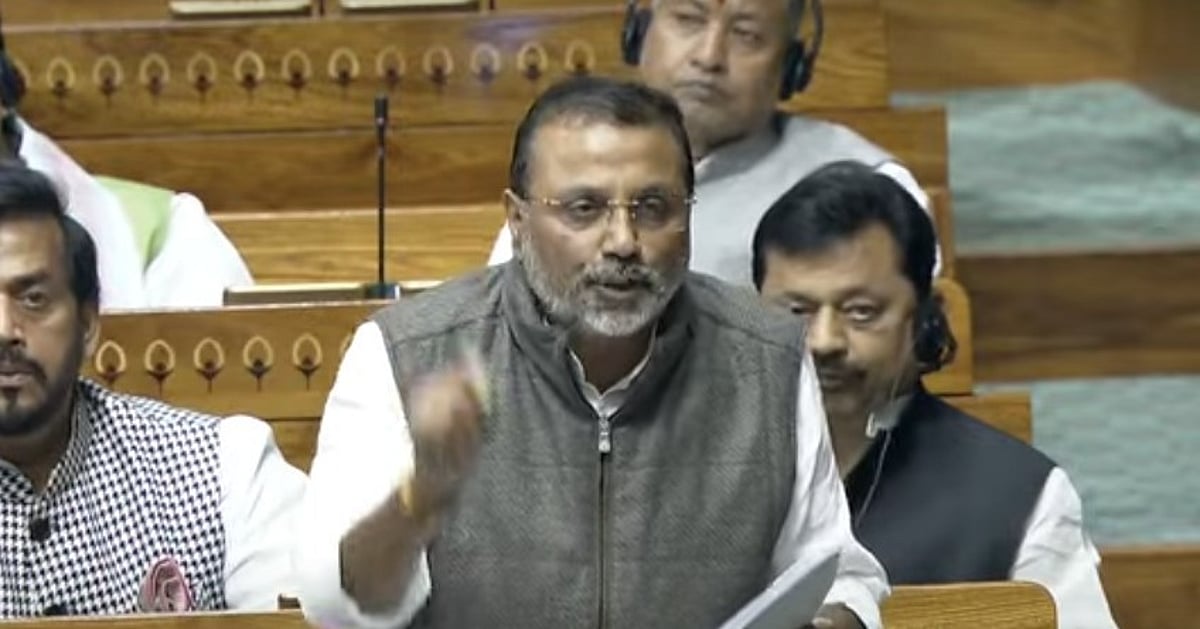

In Jammu and Kashmir , fatalities were 121 in 2012 before this government took over, but they later surged past 320 in 2020. Despite the abrogation of Article 370, fatalities remain high, with over 127 reported in 2024, contradicting claims of restored normalcy despite disproportionate and exclusive reliance on use of force. In a recent speech in the Rajya Sabha, Union Home Minister Amit Shah used the term “ruthlessness” in the context of dealing with Naxalites.

Your comments? Ruthlessness is not something a government should boast about, especially against its own people. As the government belongs to a right-wing political party, it harbours an intrinsic animosity toward anything ideologically grounded in the Left. Maoist insurgency is now confined to a few districts, mainly in Chhattisgarh’s Bastar, with limited activity in neighbouring States.

This is the right time for outreach and resolution, as many would surrender if given an honourable path. In the 1960s and ’70s, many former Maoists joined parliamentary democracy. While some leaders may stubbornly cling to failed objectives, most will see the futility of their struggle.

Instead of setting a deadline for Maoism’s end, the focus should be on reconciliation. “The current government appears to focus primarily on fatalities as the key marker, which is a flawed approach. This approach is problematic as it incentivises security forces to maximise kill counts.

” Ajai Sahni Executive director of the Institute for Conflict Management and South Asia Terrorism Portal What risks would arise if the deadline is not met? And how might it affect national security in the long term? It will have a zero impact. They have ceased to be a national threat. But it has the potential to discredit the government.

The government’s adamant approach may pressure them into creating occasional disturbances merely to assert their presence here and there at the local level. In States such as Jharkhand and Bihar, they are already working like local extortion gangs unlike Maoist insurgents. Insurgencies end through political settlements, not just military action.

Security forces can create conditions for resolution, but a lasting solution requires dialogue. Unlike northeast insurgents with external support, Maoists operate entirely from Indian soil, making complete eradication difficult. Small groups may continue sporadic attacks to challenge government claims, but Maoist-initiated operations are now rare.

Most violence stems from security force actions. It’s time for the government to act with authority and generosity, offering Maoists a dignified path to surrender. Some security experts have praised the new surrender policy announced by the Chhattisgarh government.

In the current scenario, top Maoist leaders are unlikely to surrender. While rewards and rehabilitation exist, they won’t end the insurgency. Instead, the state must engage in outreach, even without suspending operations, to urge the leadership to accept reality.

Expecting to eliminate every last Maoist is unrealistic. With the state in a position of dominance, now is the time for a political initiative, offering an honourable exit to minimise further violence. Also Read | In Chhattisgarh, the war on Maoists becomes a war on Adivasis How do you foresee India’s internal security strategy evolving beyond 2026, considering the results of the ongoing anti-Naxal campaign? Since 2001, insurgencies in India have steadily declined, with occasional spikes here and there.

This was due to global shifts post-9/11, which legitimised strong counterterrorism measures and pressured state sponsors of terrorism. By 2013, fatalities linked to the Maoist insurgency had declined to 418 from over 1,013 in 2008. Last year, the toll stood at 400.

Before 2014, security forces had already improved intelligence, operational efficiency, and local force deployment, significantly weakening Maoist dominance. The Andhra Pradesh model, initially perceived as merely involving Greyhounds, came to be recognised as a sophisticated operation or framework. It relied on intelligence-led operations targeting the upper echelons of leadership.

This demonstrated a steady process of adaptation and consistent strengthening by the security forces. The current government has largely continued this approach, adding a more explicit emphasis on “ruthlessness” but without any fundamental shift in policy. The decline in insurgency is a result of long-term security apparatus consolidation over the past several years, not any dramatic new strategy.

Featured Comment CONTRIBUTE YOUR COMMENTS SHARE THIS STORY Copy link Email Facebook Twitter Telegram LinkedIn WhatsApp Reddit.

Top

Insurgencies end through political settlements, not just military action: Ajai Sahni

“Ruthlessness” is not something a government should boast about, says the conflict analyst.