New Delhi: It was sometime in the year 2013 that Kabir Paharia first resolved to become a doctor. He was seven years old then, and the main catalyst for his decision was his mentor, family friend and surgeon who then practised at Vardhaman Mahavir Medical College and Safdarjung Hospital in Delhi. Kabir had also undergone a few corrective surgeries at that hospital, on both his hands and feet, between the ages of three and five, owing to a rare birth condition called Amniotic Band Syndrome, where an amniotic sac strand may become wrapped around the fingers or toes of a foetus, resulting in “syndactyly”, or fusing of fingers or toes.

“The doctor who carried out these surgeries was a grandfather-like figure for me, and I referred to him as ‘dadu’. I drew inspiration from him, as he showed me how much effect a doctor can have on a person’s life,” Kabir says. This is what drove Kabir to pursue medicine, prompting him to take up science in the 11th standard, as well as enroll at Vidyamandir coaching centre to prepare for his life goal—clearing the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (Undergraduate) or NEET UG, a key exam for admission in MBBS and other medical courses.

However, despite mentally preparing to be a doctor for a decade, taking coaching classes, and clearing the NEET-UG 2024 in PwD (Persons with Disability) category with the 176th rank and scoring 542 in a 720-mark paper, Kabir is in limbo today. The reason—the National Medical Commission’s guidelines from 2019. Notably, one of these guidelines requires that for entry into medical courses, a candidate must have “both hands intact, with intact sensations, sufficient strength and range of motion”, which are considered “essential” for eligibility for medical courses.

Kabir has twice been assessed by a medical board and declared ineligible to purse medical studies. After the second assessment results, he moved court. He got some hope after a three-judge Supreme Court bench, on 2 April this year, ordered a fresh assessment of his disabilities, in line with the top court’s 2024 and 2025 rulings in Om Rathod vs Director General of Health Sciences , and Anmol vs Union of India , respectively.

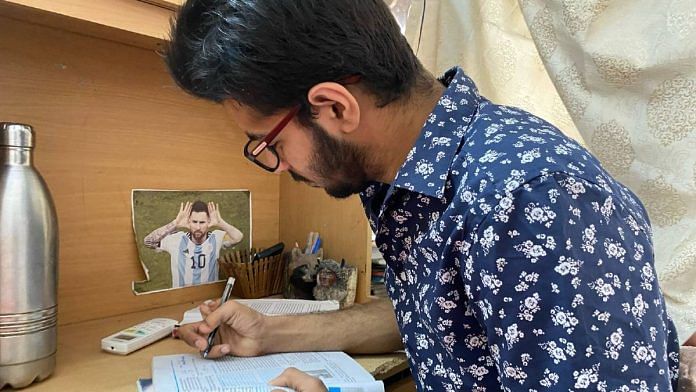

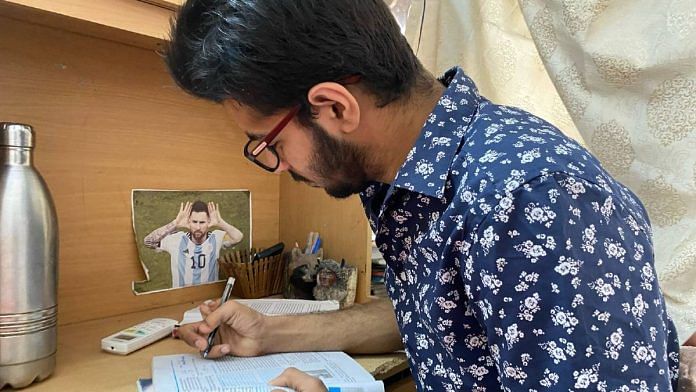

In the latter case, the SC had lamented the 2019 guidelines and directed the issuance of fresh guidelines for admitting persons with disabilities into medical courses. “The committee formulating the guidelines must include experts with disability or persons who have worked on disability justice,” the two-judge bench had ruled, adding that these guidelines must comply with the Supreme Court judgments. Kabir Paharia at his home in Shalimar Bagh in Delhi | Photo: Khadija Khan/ThePrint This means that a new committee will assess Kabir’s eligibility for pursuing medical studies and thus decide his fate.

An AIIMS board has been constituted for the purpose. Its report shall be sent to the court before 16 April, the next date of hearing in his case. Going by past experience, Kabir and his family are holding their breath.

“Merely because the NMC is under the process of revising the guidelines, the petitioner’s fate cannot be allowed to hang in limbo in spite of the fact that he has performed exceedingly well in the NEET (UG) 2024 examination and stands high in the merit in his category,” the SC bench led by Justice Vikram Nath ruled in Kabir’s case earlier this month. Also Read: What’s missing in govt’s plan to secure ‘accessibility’ for persons with disabilities Kabir studied at Montfort School in Delhi’s Ashok Vihar, and currently resides at his Shalimar Bagh home, with his father, mother and uncle. An football fan and FC Barcelona supporter, his room is adorned with sketches of players, like Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo, that he drew himself.

He also enjoys watching films by Christopher Nolan. Kabir tells ThePrint that he never faced any difficulty during his years of preparation for the undergraduate medical exam, and his family decided to get a disability or PwD certificate for him on the advice of one of his coaching centre teachers, and over fears that the non-disclosure of his condition may hamper his chances of selection for medical studies. “Once I chose my subjects and started studying and attending coaching classes, I never actually faced any problems.

Initially, my family and I were unaware of the rules and regulations surrounding the selection process. Shockingly, most of these rules are not really public. You cannot even find them on Google, and we were told about them at the stage of counselling (post award of NEET scorecard) in September 2024,” he says.

Kabir added that his family got the disability certificate made only two months prior to the exam in June last year. The delay was due to the family’s dilemma that despite Kabir’s “congenital absence of multiple fingers on both hands and the left foot”, he is extremely functional, to the extent that he can play sports like football, participate in athletics and also sketches with precision. He scored 90 percent marks overall in his 12th board exam, he says.

It took the family and Kabir some time to realise that his “disability” would become a hurdle in his medical studies. Sketches made by Kabir over the years | Photo: Khadija Khan/ThePrint “On the basis of the PwD certificate, they (medical board) started to say we won’t allow it, even though this condition does not hamper my performance or functionality,” Kabir says. “I have never even required a scribe during the exams I have given so far.

” He explains that because of his functionality, he never looked at his condition as a disability, and thus found himself at a loss of words upon being rejected for admission to medical colleges, despite putting in years of hard work and even securing the required marks. Amid his legal tussle, starting from the Delhi High Court last year to the Supreme Court now, Kabir is in the process of preparing for the NEET-UG exam all over again. Heartbroken, yet undeterred, he is yearning for a future where his hard work does not go to waste.

“With the legal battle and the blow of rejection, I have had an extremely uncertain and difficult year,” he says. Although the Supreme Court has directed the NMC to revise its guidelines, in accordance with its earlier judgments, this is yet to be done. Moreover, Kabir did not encounter any positive outcomes in his previous two assessment rounds, which were ordered by single and two-judge benches of the Delhi High Court.

In the first assessment round conducted by a medical board, Kabir said his hands were checked briefly, but the doctors did not make him do anything to test his functionality. “After this, I was told to wait outside and subsequently handed a piece of paper saying that I was ill, and had 68 percent disability,” he explained. The existing NMC guidelines with respect to persons with disabilities allow for 40-80 percent disability.

In some cases, even persons with disabilities beyond the 80 percent limit have been considered for admission to medical courses. Kabir said he met a similar fate in the second round and now has to face a third. “Here also, they did not make me do anything.

They simply took me to another room and explained to me why I could never become a doctor. This was after making me and my family wait for four hours,” he tells ThePrint. “If we had been given a legitimate reason, then we could accept the decision taken by the board.

But without any cogent reason, why would we accept the decision?” he asks. “Such shallow, loosely-defined and ambiguous NMC norms, which don’t serve anyone, have been challenged in several SC cases,” Kabir adds. “Saying that we want both hands doesn’t mean anything.

These loosely-defined rules are only exacerbating the issue.” “Even though the National Medical Commission emphasises competency-based assessment, and evaluation of students on the basis of their demonstrated abilities, these norms fail to specify what abilities the persons must have or show,” he adds. The way forward in such cases could involve testing the functionality of the candidate, which could include aspects like whether one is able to perform certain activities, he further says.

According to Kabir, if his dream to become a doctor comes true, he wishes to be one who specialises in radiology, pathology or dermatology. He has momentarily hit pause on his passions of watching movies, sketching and football, and is once again consumed by the NEET exam, while waiting for the court to announce the outcome of his case on 16 April. (Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui) Also Read: Disability rights intersect with economy, commerce, health.

Policy should reflect that var ytflag = 0;var myListener = function() {document.removeEventListener('mousemove', myListener, false);lazyloadmyframes();};document.addEventListener('mousemove', myListener, false);window.

addEventListener('scroll', function() {if (ytflag == 0) {lazyloadmyframes();ytflag = 1;}});function lazyloadmyframes() {var ytv = document.getElementsByClassName("klazyiframe");for (var i = 0; i < ytv.length; i++) {ytv[i].

src = ytv[i].getAttribute('data-src');}} Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. Δ document.

getElementById( "ak_js_1" ).setAttribute( "value", ( new Date() ).getTime() );.

Politics

How NMC’s ‘hands intact’ rule has left the fate of an MBBS aspirant with rare condition in limbo

Delhi's Kabir is in the midst of a legal battle to realise his dream of studying medicine. After SC's order, he is set to undergo fresh assessment of his disabilities—for the third time.