Art teacher Daniil Klyuka believes the headmistress of the provincial Russian school where he worked reported him for doodling horns on pictures of officials in a newspaper. The 28-year-old was later sentenced to 20 years in jail. His case illustrates the severity of the crackdown on dissent -- both real and imagined -- in Russia since the invasion of Ukraine.

And how ordinary Russians are again living under the shadow of denunciation, the old Soviet practice of informing on colleagues, neighbours, friends and even family. Until last winter, Klyuka lived a quiet life in Dankov, a town 300 kilometres (190 miles) south of Moscow, whose chief claim to fame is that the renowned novelist Leo Tolstoy died at a railway station nearby. On the website of the state school where he worked, there are still photos of the classroom where he taught, decorated with posters of famous paintings, including a self-portrait by Van Gogh.

But Klyuka's life took a nightmarish turn one day in February 2023 when he was arrested by masked members of Russia's feared FSB security service. He was accused of sending 135,000 rubles (around $1,380) in cryptocurrency to Ukraine's ultranationalist Azov brigade, classified as "terrorist" in Russia -- a charge he denies. Klyuka believes all this happened because he idly scribbled moustaches, horns and beards onto photos of officials in a pro-Kremlin newspaper that staff at his school were expected to read.

AFP has been able to piece together his descent into the depths of the Russian penal system, where prisoners can sometimes disappear without a trace, through letters he has exchanged with a Russian anti-war activist exiled in Italy. Antonina Polishchuk, 43, gradually learned what had happened to him after responding last year to an appeal to write to Russian political prisoners, some of whom have the right to receive letters. She decided to write to Klyuka because of a shared love of architecture and anime.

"I'm interested in architecture and my daughter is interested in anime, so I thought we could write to him together," she told AFP. Through the letters they exchanged on an official government platform, she found out Klyuka was being prosecuted for "treason" and "financing a terrorist organisation" -- charges often used by Russia to crush opposition to the war in Ukraine. Klyuka believes his headteacher secretly informed on him.

Contacted on social media, Irina Kuzicheva did not reply to AFP's requests for comment. A wave of denunciations has swept the country since March 2022 when President Vladimir Putin called for "traitors" to be hunted and for "society to purge itself", after the invasion of Ukraine. Groups such as "Veterans of Russia", led by Ildar Rezyapov, have denounced hundreds of people to prosecutors, including actors and artists.

Civil servants as well as ordinary Russians have also taken it upon themselves to report neighbours and colleagues -- some driven by greed, ambition or envy, others by the desire to remove an adversary. Klyuka's mistake was to leave the newspaper he had doodled on behind at work. "I would sometimes write 'demon' on the foreheads of some of the government representatives" in the photos, he wrote in one letter.

Klyuka said FSB agents searched his home, confiscated his phone and then tortured him "in a cellar". The agents said they found suspicious money transfers on the phone. The teacher said he was tortured into confessing that he had donated to the Ukrainian military, before insisting he had sent money to a Ukrainian cousin whose family had fled the invasion.

The cousin, Mykyta Laptiev, confirmed to AFP that he received the money and had used it to take care of his sick father, Klyuka's uncle. It was impossible to verify the prisoner's other claims since the case was classified as secret by the FSB and lawyers can be jailed for discussing it. After corresponding for six months, Polishchuk realised that Klyuka had no real legal representative -- only a state-appointed lawyer who "de facto worked for the government".

His family could have hired a lawyer themselves, she said, but "they were really intimidated. The FSB scares everybody." Finally the banned Memorial rights organisation, which is active in exile, paid for a new lawyer.

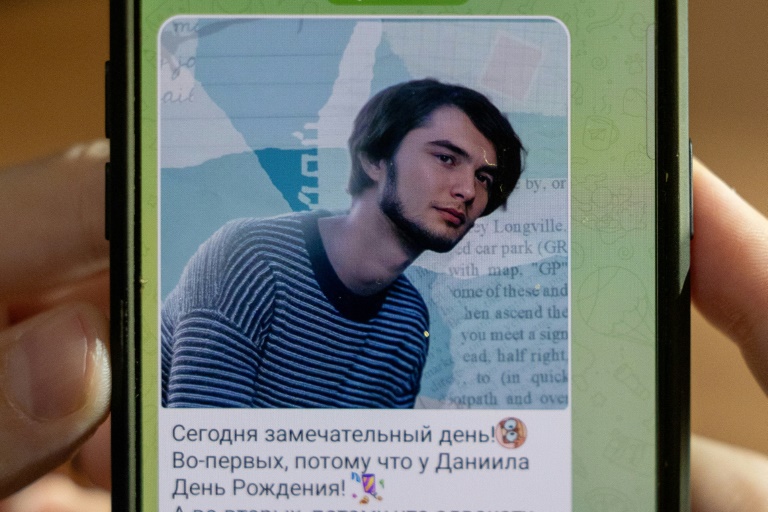

Polishchuk also created a Telegram group to support him. She struggled to find a picture of Klyuka, finally finding a photo taken during an art lesson. Slim with thick black hair, he is smiling and holding a wooden mannequin used to teach pupils how to draw.

Sergei Davidis, head of the political prisoners' support programme at Memorial, said it was typical for trials like Klyuka's to be held in secret to silence the defendant and hide the scale of repressions. He said "schools are a conservative sphere where particular attention is paid to ideological loyalty," and that Klyuka would have stood out with his anti-war views. "Denunciation was the trigger for this prosecution.

But such people are also being prosecuted without any denunciations in all of Russia's regions," he added. Without access to Klyuka's case file, Memorial -- a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022 -- is unable to add him to its official list of 778 political prisoners, which it says is the tip of the iceberg. Memorial estimates at least 10,000 people are being held for some "political" motive in Russia.

Around 7,000 are Ukrainian civilians, according to Kyiv's Center for Civil Liberties. One such prisoner, Ukrainian journalist Victoria Roshchyna, died behind bars in September. Russia's OVD-Info organisation, which monitors detentions and courts, said there are around 1,300 people behind bars on political charges, but hundreds or even thousands of other cases involve treason, sabotage and refusing to fight in Ukraine.

Rights groups often only learn of them from chance encounters between prisoners who then pass on information. Klyuka, for example, wrote to Polishchuk that he met Alexei Sivokhin, a Russian-Ukrainian dual national who fought in Ukraine and was detained in 2022 while visiting Russia, during a prison transfer. "He had been in prison for two years, alone in a cell without any other contact.

If it wasn't for Daniil, he would have remained unknown," said Polishchuk. Polishchuk is also keen to identify the informers behind these cases, so they can be brought to justice "when this regime falls". She blamed the lack of punishment for those who informed on others during Soviet times for the revival in denunciations.

Polishchuk included questions from AFP in a letter sent to Klyuka. A week later she received a reply from the Matrosskaya Tishina prison in Moscow. Polishchuk has recently received several letters from Klyuka where his entire message was scrawled out by the censor, but this one was legible.

In spidery handwriting, Klyuka said: "The person who denounced me has two brothers directly taking part in combat (in Ukraine). You can see what was going on in their head." Russia now is like "a snowball rolling down a mountain", he wrote, or "a car whose brakes have failed".

He talked of his love of drawing, which he said allowed him to "see things that have never existed". The day after his letter arrived, Klyuka lost his appeal and was finally sentenced to 20 years in a "strict regime" penal colony, able to receive just one visit and one parcel per year. He will now be taken to the colony.

Such transfers are carried out in secret, often taking many weeks, and lawyers and relatives only find out where they are after the prisoner's arrival. At the end of his letter, Klyuka wrote that Russians like him who speak out are "persecuted and hated" while "most people closed their eyes and have never opened them again." "If the world hears this message, I ask you to not close your eyes," he added.

He finished on a more upbeat and chatty note, asking Polishchuk about her work and sending her a kiss..