When Premier Doug Ford’s administration in 2021 to extend a Toronto subway line to Richmond Hill, it looked different from what the previous government intended to build. Instead of going straight north, a portion of the Yonge north subway would swerve eastward off Yonge Street, then run under a residential neighbourhood, a public school and a tributary of the East Don River before for its final stretch. It would also include two new stations in the middle of land owned by some of Ontario’s most prominent developers.

The route change, selected by Metrolinx and endorsed by the Ford government, paves the way for a profitable boon for the developers, who plan to build and sell more than 40,000 new condo units in a thicket of skyscrapers surrounding the two stations. With Ontario facing a housing shortage and a growing population, a spokesperson for the premier’s office said it’s important that transit lines be accessible to new communities — and called the new route “the best option.” But it has also resurrected some of the same concerns that surrounded the , where decisions disproportionately favouring certain developers were sprung on local communities, leaving them questioning whose needs were being prioritized.

The new route, according to an internal assessment of three options, offered the poorest performance for commuters, with the fewest expected riders and lowest travel time savings. Meanwhile, the government has made a series of moves to make it easier for the developers’ work to proceed, overriding opposition from local governments who said they don’t have the infrastructure to support the proposed 64 new condo towers. The province made new rules that will spare the developers from having to pay billions of dollars to one of the impacted cities.

Around the same time, the Ford government struck deals with the developers, under which it says the builders will pay money to offset the costs of an extra subway station and other public infrastructure. The terms of those deals, however, are secret — and are even being withheld from the Markham and Richmond Hill municipal governments most affected by the decisions. The Premier’s office said the new route, chosen by Metrolinx, is “the best option” to serve the needs of York Region’s growing population.

“Our focus remains squarely on building the transit, homes and infrastructure that Ontario needs to support the province’s growth,” the premier’s office’s spokesperson said in a written response, adding that previous plans along the original route for the Yonge subway extension “did not meet the needs of York Region’s rapidly growing population.” The new route, which is the most cost-efficient option to build the $5.6-billion subway extension, allows “expansion of the line and more stations to better connect people across the region, while addressing concerns raised by the municipality.

” Local and provincial officials have for decades wanted a Yonge subway extension. In 2009, the environment minister of the Liberal provincial government of the day greenlit a plan for a fully underground, six-station route. The project remained unfunded and dormant until 2019 when the Ford government introduced legislation to upload the delivery of Toronto’s future rapid transit projects, including the Yonge subway extension, to the provincial agency Metrolinx.

At that time, the cost for the originally planned six-station route was estimated to be $9.3 billion, nearly doubling what the Ford government had budgeted. They could only afford to build three new stations, Metrolinx said at that time.

The agency had quietly considered three alignments. Eric Miller, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Toronto. The chosen option, referred to in Metrolinx’s initial business case as Option 3, was the cheapest.

It was also the poorest performer from a transit perspective. It offers the fewest expected daily riders, fewest daily travel minutes saved and fewest “net new transit users” projected. “It’s building an inferior, suboptimal alignment.

And you see it in their own numbers if you go into this business case,” said Eric Miller, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Toronto. The agency also compared the travel time of different trips between York Region and Toronto and concluded Option 3 gave the least total time savings. It’s also expected to draw nearly 16,000 fewer daily boardings than the original route.

Metrolinx’s analysis suggests the chosen route could also result in less ridership revenue, more greenhouse gas, and more traffic on the road in the area than the other two options. The premier’s office said the route choice was “based on the engineering expertise and maximized community benefits.” The route change also requires less excavation and is less disruptive to the community.

While Option 3 was estimated to cost less than the original route to maintain and operate, tight curves would make it more complex to build, and could also lead to higher maintenance bills in the long run, transit experts told the Star — costs that would end up being the responsibility of the Toronto Transit Commission. “It’s going to be an ongoing maintenance cost because the tracks will wear out faster, and it’ll be a slightly slower trip,” Toronto transit expert Steve Munro said. The new route will create a “transit hub” at Bridge Station, Metrolinx and the premier’s office said, connecting the Yonge subway line with GO Transit and local buses.

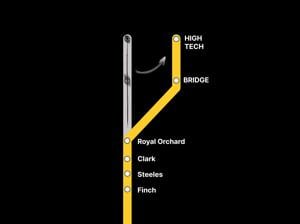

It will also make it easier to extend the subway north along the existing rail line, something that wasn’t possible under the other options. Option 3 is also at least $1 billion cheaper than a three-station version of the original route in capital costs, according to Metrolinx’s analysis. The new route will include five stations.

The two northernmost stations — “Bridge” and “High Tech” — are both in the middle of 42 hectares of land owned by the same group of developers. Premier Doug Ford, seen in 2019 with a map that featured the original planned route for the Yonge subway extension. Land records show that since the mid-2000s, that group of development companies had been assembling lands that would become the Bridge station area.

By 2021, the firms already owned more than 60 per cent of the land in a 25-hectare area. These companies all list Angelo De Gasperis as a director. Angelo, alongside his brothers Tony and Fred De Gasperis, founded Condrain in 1954 as a concrete and drainage company which has now developed into a major construction empire based in Concord, Ont.

To the north of Highway 7, on the Richmond Hill side of what will become the new route, four De Gasperis-controlled companies own much of the land, which they started acquiring in the late 1990s. Some of these properties also abut the terminus station on the original route. Three of the corporations list Angelo as a director and the other is headed by Angelo’s nephew Jim De Gasperis and their business partner Marc Muzzo.

Developer Sam Balsamo is also a director of two of the companies. None of them responded to repeated requests for comment. Representatives from Condor Properties and politicians celebrate the August 2020 groundbreaking of the new Walmart distribution centre.

Among the attendees are developers’ Marc Muzzo (left) and Angelo De Gasperis (second from the left). The De Gasperis-controlled companies Condor and Metrus hired former Progressive Conservative MPP Frank Klees to lobby on their behalf (Klees did not respond to the Star’s questions.).

A week before the new route was announced in March 2021, Klees updated his information on Ontario’s lobbyist registry to include a new lobbying goal: to “facilitate and assist” in negotiations with the province to develop a “proposed transit oriented community” on their land. Transit-oriented communities, or TOCs, are part of a provincial program introduced in July 2020 to build new transit. Under the program led by Infrastructure Ontario, developers are allowed to build higher-density buildings near transit, which are more profitable for them, and they offset the public cost of building public transportation.

The goal is to make vibrant, high-density communities connected to a public transit station. All TOC negotiations with developers are handled by “non-partisan, arms-length agency officials” inside Infrastructure Ontario, the premier’s office said. After the Ford government announced the new subway route, the De Gasperis companies started acquiring more land.

One company purchased a 2.55-hectare plot of land near the proposed Bridge station from the provincial government for $175 million. The land was considered surplus, the spokesperson for the premier’s office said, and was “identified as needed for a TOC priority project.

” The land was sold to the De Gasperis company at fair market value. Another company called 10 Cedar Avenue — headed by Angelo De Gasperis — also bought two parcels of land for $30 million from a landscape supply company in early 2022. The lots are located just east of the CN rail lines where the developers are planning to erect a 65-storey condo tower.

“I didn’t want to sell the land,” said Tony Pacitto, president of the landscape company. Pacitto said he felt compelled to sell when a representative from Condor approached and told him the province “only wanted” to partner with them, not an individual landowner like him. “When these guys come and kind of push you and they’re with the government, they’ve got the power to do it.

Sometimes you’ve got to take what you can and move on,” he said. In September 2021, the Ford government graced the De Gasperis group’s lands surrounding the planned Bridge and High Tech stations with TOC status. With the TOC designation, the developers proposed to build about 18,000 additional condo units than they would’ve been able to before the province stepped in.

The planned development was met with immediate pushback from Richmond Hill and Markham councils. The developers’ proposal would see a total of 64 condo towers, many as high as 80 storeys, built between the two sites over several decades. They are expected to bring in roughly 80,000 residents.

Since 2008, Markham officials had eyed the area around what will now be Bridge station as a vibrant community. Building plans envisioned walkable streets, public transit and open space — a little bit of everything for locals so that the area could more seamlessly integrate with neighbouring communities. In Richmond Hill, the land around what will become High Tech station had been expected to transform into “a new downtown” with a diversity of architecture and building types.

The new plans, and the dense grouping of towers they would bring, did not adequately consider the additional schools, libraries, and community centres that would be required with the expected influx of future residents, the region cautioned the province. York Region’s chief planner wrote four letters appealing the Ford government to revise the plans. One of his reports warned of “unanticipated consequences” if they went ahead.

In April 2022, the province sealed the fate of the two TOCs by wielding another of its developer-friendly tools. Former Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing Steve Clark issued two enhanced (MZOs) to override the local authorities and greenlight the large-scale development plan. MZOs bypass municipal planning rules and can be used to fast-track developments.

The MZOs cannot be appealed. “There’s a lot of overlap between this development and the Greenbelt deal. They all follow the same kind of pattern,” said Graham Churchill, a former director of the Federation of Urban Neighbourhoods.

“Let me do a deal with the developer but give away some value so that we can get some money to get something done, but without thinking about the broader impact of how does this solve the problem of the overall region.” In a 93-page report to the legislature, Bonnie Lysyk said the Tories did not need the 15 parcels of land to achieve their promised target of The government’s zealous use of MZOs came under scrutiny amid the Greenbelt scandal, which put a spotlight on Premier Ford’s decision to open up the protected area for development and how a flawed process favoured well-connected developers. (The branch of the De Gasperis family behind the companies set to benefit from the Yonge subway extension did not own land included in the Greenbelt land swap.

) Following damning reports by the Auditor General and Integrity Commissioner, Ford reversed his government’s plans to open up the Greenbelt and apologized to Ontarians. Clark, the housing minister, resigned. His successor Paul Calandra began reviewing the minister’s zoning orders issued during Clark’s time.

The two enhanced MZOs for the TOCs in York Region are considered “provincial priorities” and not part of the review, the government said. The province’s actions along the planned subway extension don’t just pave the way for possible big profits for the developers — they may also offer them great savings. Previously, Markham had the power to require developers to contribute land to the city for parks or pay cash-in-lieu for the impacted TOC land.

That cash amount was to be calculated based on the numbers of proposed units and land value and enforced through a city bylaw. Markham was expected to rake in $2.2 billion.

That is about four times the city’s entire budget in 2024. But new legislation would change that. The More Homes for Everyone Act altered the parkland requirements for transit-oriented communities.

In Markham, it means the developers in the Bridge TOC will no longer have to pay any cash-in-lieu to the city. This “will have a lasting impact on the city’s ability to provide for adequate parkland to support complete communities,” Pody Lui, Markham’s spokesperson said. The premier’s office said the changes for parkland dedication on these sites “will increase cost certainty and the speed with which subways and increased housing will be built.

” The developers in the TOCs will still pay development charges and community benefit charges to Richmond Hill and Markham. Both cities said they cannot yet calculate how much money the developers are expected to contribute as the development plans are not finalized. The province will also collect money from the developers, which it says will offset the cost to build Royal Orchard Station in Markham, to be located just south of where the subway line will veer off Yonge Street.

As part of the province’s agreement with building partners at these TOCs, a portion of revenues realized by the province will go toward the building of libraries, community centres and affordable housing, according to the premier’s office. The premier’s office would not say how much money the province will receive from the developers in the deal. A knock on the door was all the heads-up Dwight Richardson got before he and his family found out just how much the Yonge north subway reroute was going to impact their home.

It was December 2021 when the homeowners heard from the provincial agency for the first time that the subway extension will tunnel directly under their two-storey house, Richardson said. This was more than a year after Metrolinx had already started eyeing the new route and six months after it had announced it had chosen it over other options. “The whole problem with this .

.. is the silence,” Richardson said.

Frustrated with the amount of information Metrolinx shared in open houses and community meetings, the homeowner took it upon himself to find out more. He filed a freedom of information request seeking records that included the detailed drawings and the concept design for the subway extension. They were denied.

He said the secrecy just foments more questions and suspicion among residents. “If these are all such good plans, then tell us about it.” The provincial transit agency says it has listened to the public and continues to refine plans for a route that could save billions while delivering more transit benefits for the people of York Region and Toronto.

The latest version of Metrolinx’s plan will tunnel under 20 homes and 15 other properties, updated from its earlier design that would have run under 63 properties. The tunnel will also run deeper to lessen its impact. “We are determined to make the project the best possible fit for the communities it will serve, and there will be many more opportunities to share feedback,” said Metrolinx spokesperson Andrea Ernesaks.

When it comes to the deals made on the transit-oriented communities, even York Region and the city governments of Markham and Richmond Hill were kept out of the loop. In April 2022, the provincial government entered into confidential commercial agreements with Metrus and Condor for the developments of the TOC lands. York Region is not privy to the details of the deals between the province and the De Gasperis companies.

.