It’s easy to miss the Auric Room 1915, the new private members’ club at Lone Mountain Ranch resort on Montana ’s North Fork Gallatin River. It opened this past spring, tucked away upstairs above the lobby and reached via a small mahogany elevator in the wood-framed main-lodge building. Those who know to step inside are whisked up to a cramped corridor, where a hostess offers a polite greeting and coats—a floor-length vintage fur, perhaps, or an oversize woolen shrug—in case you need to duck out onto the cigar terrace.

Then she requires everyone to hand over their phones, which she stows in a wall of vintage safe-deposit boxes. Auric Room 1915, named after the year this ranch was established, is a small space, barely 1,200 square feet, with high ceilings and dark wooden paneling. The decor is wittily maximalist—Elton John’s idea of a cowboy saloon—with rawhide banquettes and giant antlers for a chandelier.

The same goes for the food: Tables are piled high with fist-size pots of caviar, which is scooped up with crispy homemade chips, and drinks are served in hefty crystal glassware. Most notable, though, is how conversation spills over between strangers mingling together in this speakeasy-like hideaway; one group waves a newcomer over to ask about his boots, and soon he’s sitting down to chat. “We wanted this to be a mannered environment, one where if you sit next to each other at the bar, you can be social,” says Paul Makarechian, noting that the cell-phone ban forces old-fashioned socializing, “We have strict non-solicitation rules.

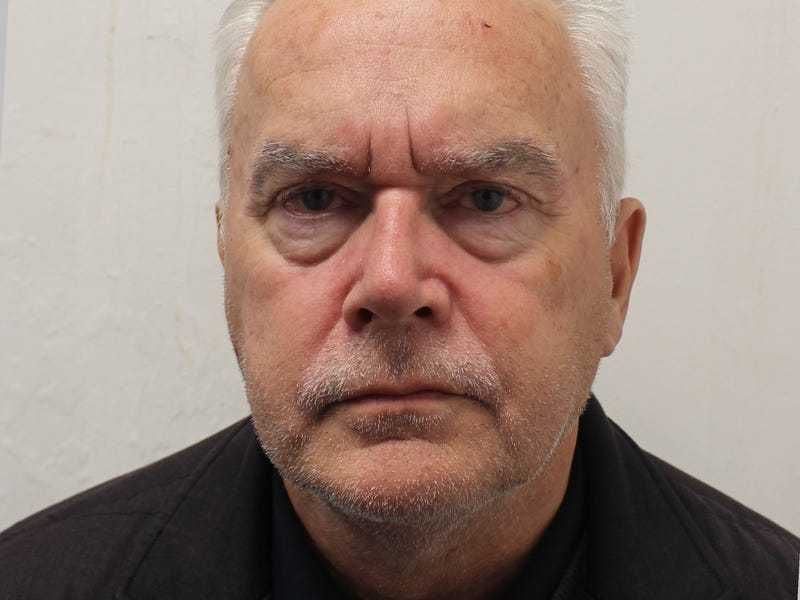

It eliminates that quick, ‘Let me text you my number,’ though after a few drinks, people are trying to memorize them.” Makarechian is cofounder of the resort and its CEO, a real-estate developer–turned-hotelier who lives with his family nearby. He’s dressed in classic Western wear, with a jaunty Stetson at hand.

The members’ club is mentioned only in passing on the hotel’s website—a deliberate choice, he says—and will be picky as to whom it allows to pay the $5,000 initiation fee and $5,000 annual dues; for the first year, he has capped membership at 144, though hotel guests are invited to spend an evening there if they wish. The focus is squarely on anyone who’s seriously connected to Montana, whether a longtime local or one of the wealthy new Big Sky arrivals. “If somebody ends up making Montana part of their committed lifestyle, how do they mingle with other individuals who are here? he explains.

“We wanted to curate a small community, fun people from different walks of life, whether those who had four or five generations of history here or the new Montana, someone who’s just bought a home and is trying to enjoy it.” That new Montana is growing fast. Well-heeled newcomers in nearby Bozeman arrive from California at such a clip now that it has earned a new nickname: Boz Angeles.

But Auric Room 1915 is emblematic of a larger trend toward such private establishments, which are enjoying a boom unseen since America’s Gilded Age. A decade ago there were 90 high-end members’ clubs in the U.S.

, a number that has risen 66 percent, to 150 today, according to data from Pipeline Agency, a consultancy in the sector. Europe experienced a similar surge over the same period, with the count climbing from 120 to 200. More immediately, consider other hotel-adjacent openings, such as the Poodle Room, a new Rat Pack– inspired spot at the top of the 67-story hotel tower of the Fontainebleau in Las Vegas , or Aman New York ’s aggressively exclusive option, where initiation will set you back $200,000.

The San Vicente Bungalows , the celebrity favorite in Los Angeles where cell-phone cameras are theatrically covered with branded stickers, will soon have an East Coast outpost in what was once the Jane Hotel in New York’s West Village. It will be a short walk to Chez Margaux from Jean-Georges Vongerichten, which repurposes the 18,000-square-foot space he formerly ran as Spice Market. Major Food Group , which operates Carbone and other buzzy restaurants, has recently expanded into this niche, with ZZ’s Club in both Miami and New York; on the top floor of the latter is Carbone Privato, a punched-up riff on the already swaggering original.

And operations that started in London are now arriving stateside, including Maxime’s, the first American site from club scion Robin Birley (of 5 Hertford Street fame), which will soon open on New York’s Upper East Side. And that’s just in the U.S.

The global boom includes Greece’s 91 Athens Riviera , the Resort, and wine- driven 67 Pall Mall , which has cloned itself in London, Hong Kong, Singapore, the Swiss ski village of Verbier, and soon, Melbourne plus Beaune and Bordeaux in France. Meanwhile, the Arts Club Dubai is a souped-up, supersize sibling to its namesake in Mayfair, stretched across 65,000 square feet in the financial district. Perhaps the clearest sign of the potential market is the proliferation of companies established expressly to help would-be owners with a turnkey private-club solution.

The list includes Pipeline , based in Manhattan Beach, Calif.; Sevengage in London; and New York’s Collectio Group . Peter Cole is the latter’s cofounder and CEO.

“In the next three to four years, you’re going to see two things happen simultaneously: One is that clubs will continue to proliferate, but at the same time, a number of them will go out of business,” he tells Robb Report, comparing the industry’s outlook to the recent streaming wars on TV. “In the golden age of content, you couldn’t watch it all, even if you tried jumping back and forth. It’s the same thing here.

Clubs are coming out with beautiful spaces and incredible membership lists, but there’s not always enough to keep people engaged. A number of them are not going to be successful.” Melody Weir , a New York–based interior designer who moonlights as a membership consultant, agrees.

“After the pandemic, it’s like they opened Pandora’s box,” she says. “Everyone wanted to get out and be seen, but the problem is that a lot of people don’t do enough research.” The members-only model, of course, isn’t new.

The modern incarnation began in Britain, where Georgian-era coffee houses evolved into more formal, men-only meeting places such as the Garrick Club and the In & Out , a naval club nicknamed after the carriage-gate signs at its original site. Wealthy Americans adopted the idea later in the 19th century, resulting in clubs including the Knickerbocker and the Metropolitan , whose inaugural president was J. Pierpont Morgan.

There were university versions, too (Yale, Harvard, and Cornell among them), as well as societies clustered around shared interests, such as the Anglers’ Club; the Colony Club, founded in 1903, was New York City ’s first such establishment for women. All were centered in major cities and so suffered during the late 20th century when thriving suburbs siphoned off the elite into golf or country clubs instead. Today, the pendulum has swung back toward urban living, gifting private city versions momentum and an audience newly primed to join following the isolation of the pandemic.

Some are see-and-be-seen spots à la Maxime’s, while others, such as Auric Room 1915, are geographic, a way to bring together disparate groups in an outlying location. A shared interest anchors 67 Pall Mall, which is expressly intended to appeal to oenophiles, according to founder and CEO Grant Ashton, who initially funded the project with a fortune earned via three decades in banking before recruiting more than 500 investors. “The worst sort of club is the one where you have some fancy-schmancy membership person, some sort of ‘It’ person, who chooses their friends to be members,” he says.

“We have a specialist purpose: We are a community based around loving wine, and we subsidize our wine list with a chunk of our membership fees so it’s cheaper.” But, he adds, “We do make money. If you can make membership clubs work, they’re a very lucrative model.

” Indeed, experts say the appealing financials of successful social clubs are key to their current renaissance. Jamie Caring, son of billionaire restaurateur Richard Caring, was Soho House’s chief marketing officer before setting up his own consultancy, Sevengage. “If you get it right, the EBITDA [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization] graph has a 45-degree angle that carries on and keeps going up,” he explains.

“Some people look at that and think it’s easy, with a membership fee of $3,000 and 1,000 members.” But Caring warns that while it’s reasonably simple to attract people at the outset, retaining them is a labor-intensive process that requires painstaking attention to programming in order to preserve interest: “You have to play the 10-year game,” he says, “not the two-year one.” It’s why he declines to work with would-be owners who come to him attracted solely by the return, eager to cash in quickly with whatever concept he can devise for them to deploy.

“When they shrug their shoulders if I ask them to tell me about their idea, if they don’t have a passion, can’t identify what the place is and who it’s for? I know the club won’t work.” The best ones, he says, grow organically over the initial few years and have an attrition rate below 5 percent after their first anniversary. “Once you’re into double digits, you should be raising an eyebrow,” he notes.

Private clubs can be more appealing to investors than, say, boutique hotels, because they require fewer staff per guest and margins are far higher on martinis than even a penthouse suite. According to Collectio Group cofounder and chief development officer Adam Patrizia, developers are tapping his firm to help them create similar programs for high-end residential projects, aiming to claw back some of the money spent on the increasingly lavish amenities being offered. “There was this big push to create amenity floors with hammams and workspaces, but they often just lie dormant,” he says.

“They think they can create a compelling reason for an outside member to pay to use them. And with initiation fees and recurring revenue from annuals, it’s a sound model from an underwriting perspective if done correctly.” The death of the nightclub has also allowed private establishments the room to flourish.

According to the Night Time Industries Association , a club closes every two days in the U.K. (Such a brisk rate, if untrammeled, will result in an extinction-level event by 2030.

) Local authorities are leery of granting licenses for all-night raving in cities where residents have gentrified the warehouses districts once home to such parties, but they’ll readily approve a discreet, upscale private spot. Just take Zero Bond , from longtime nightlife fixture Scott Sartiano, which cannily cloaks its party vibe in the veneer of membership. The exclusivity of a watering hole where others are vetted (whether or not their mobile phones are confiscated) has strong contemporary appeal, as does the fact that capacity is capped.

“In the social-media era, if you have a hot place and it isn’t private, it gets overrun,” Caring says. Patrizia, of Collectio, notes that “it’s harder than ever to get reservations anywhere, because there’s too much wealth out there—the wealthy are fighting each other to get a seat on a private jet.” A private club gives a certain clientele “the ability to go somewhere that they’ll always have a place at the table, where they’ll always be with interesting people,” he says.

It’s the basic idea behind ZZ’s Club, a clone of Major Food Group’s red-hot restaurants, but cordoned off from the hoi polloi who threaten to clog up the originals. Hotel-adjacent spaces, meanwhile, act as on-property halo destinations and add a handy frisson of exclusivity. They also better connect to the community by engaging residents as allies, rather than keeping them at bay, since local revenue streams are fundamental for a hotel’s survival.

It’s a lesson hoteliers were forced to relearn, painfully, during the pandemic’s border shutdowns and movement restrictions. Ben Pundole, who started out tending bar at the Groucho Club in London before becoming a promoter in Miami Beach 20 years ago and then Ian Schrager’s de facto social director, is about to spearhead a new offering that observes many of those maxims for success. The Wilde is intended as a small, global chain—perhaps five or six sites in the next decade or so—and will debut in Milan this fall, inside Santo Versace’s former residence on Via dei Giardini.

Forgoing guest rooms and a spa, it will focus entirely on food and beverage, with all-day dining and a rooftop garden. The roster will hover around 2,000 people at the outset, each of whom will pay about $1,360 to join plus annual dues of about $3,800 (those under 40 pay approximately $1,100 for initiation and $2,190 annually). Pundole, who’s about to turn 50, says it’s aimed at his peers, those roughly between 35 and 60, who experienced vintage Soho House.

He’s laser-focused on programming—that key member-retainer—but will go beyond simple screenings or on-site talks. Pundole says he hopes to secure partnerships with local museums and other cultural institutions, so those who join can expect perks throughout the city (think private viewings) that are about embedding the Wilde into their lives. “It’s one thing obtaining a member, but another thing retaining them,” he says.

“You can’t ever take a member for granted.” Indeed, that’s emblematic of a surprising tonal shift: New clubs are putting out welcome mats more often than erecting velvet ropes. Their proliferation is making it a buyer’s market, which leads to fewer exclusionary tactics and a vetting process that could be described as more business casual than formal.

Montana’s Auric Room 1915 roster has been expanding organically, with recommendations coming from the 50 or so founding members, all of whom live locally, while Grant Ashton’s criterion at 67 Pall Mall is simple: “They like wine and so would like to join a wine club.” Small wonder, then, that consulting firm GGA Partners says that 60 percent of clubs reported growth in 2022. Those who hopscotch around the globe typically acquire memberships the way they do cars, with several examples, each of which serves a different purpose.

“They’re collecting memberships,” says Peter Cole, of Collectio Group. “ ‘I’ve got my ski one, my drink one’—and we’re starting to see people collecting different geographies as well.” Cole estimates that affluent Londoners belong to 2.

7 clubs on average, and he expects the new international approach means that regulars will soon be pledging dues to about five each year. Membership directors now are tasked less with keeping out undesirables and more with ensuring that those who’ve joined stay engaged—and happy to keep paying their fees. (It’s worth noting that this makes the strategy of San Vicente Bungalows oddly old-fashioned among new clubs, in that it’s aggressively exclusive and secretive, with a rumored 3,000 board-vetted members in L.

A. and purportedly more than triple that on the waiting list for the upcoming New York site, which none of them have even seen.) Operators must also focus far more on staffing than they might assume and keep their radar on alert for those adept at learning the likes and dislikes of regulars.

“A great club encourages its staff to be themselves and celebrates their character,” says the consultant Caring. Landing the right membership director requires supreme effort and inventiveness; Caring recalls one such project, in a city he declines to name due to confidentiality agreements, in which the ideal figure for that role was the head of an important talent agency. “They were so powerful that we couldn’t ask them to give up their job and work for us,” he says.

“But why not hire that person’s personal assistant? She had the same contact book and knew everyone, but we could afford her, and she was happy to make the jump.” Likewise, when working to fill the position for a European venture, he took an even more unusual route: “We needed to find someone charismatic and ended up hiring this guy who had worked in sales for a sex-toy company—he grew up in the U.S.

but had moved to that country and learned the language. He was a flamboyant Black gay guy with a sense of humor, everyone knew who he was in that city, and he smashed the target for founder membership. But the people behind the club would never have looked at him in a million years.

” Melody Weir fits the bill in New York, where she’s discreetly helping wrangle member lists for a slew of upcoming openings. An even bigger sign of her confidence in predicting the zeitgeist: She and a friend have plans to create their own dinner club in the city soon. “More and more people are becoming more private,” she says of the broader cultural movement powering the boom.

“They’re jumping off Instagram and other social media. There’s decorum in keeping things special.”.