On August 24 this year, a publication appeared in the journal Vaccines, under a special issue titled ‘Advances in Cancer Vaccines as Promising Immuno-Therapeutics’. The article detailed the use of two viruses – measles and vesicular stomatitis, to treat a patient who had recurring breast cancer. The technique involved the injection of the viruses directly into the tumour, which lead to a stop in its growth, a reduction in its size, and allowed surgeons to excise it.

Despite the success of the procedure, no journal was prepared to publish the results before Vaccines finally accepted the paper. This was because, the team did not have the approval of an ethics committee – a primary requirement for any study involving human or animal subjects. The team argued that they didn’t need an ethics committee approval because Dr.

Beata Halassy, the lead scientist on the research, had performed the experiment on herself. The idea to use specific viruses to target cancer cells is not new. Scientists have known for over 100 years that certain viral infections cause tumours to shrink.

Experimental evidence is available since 1951 , when it was shown that that certain strains of tickborne encephalitis viruses cause an inhibition of the growth of tumours in mice. However, the first large-scale clinical trial with this idea did not happen until 2004, when a modified adenovirus named H101 was used in combination with chemotherapy to treat patients with advanced cancers in China. The first FDA-approved trial came in 2015, when a modified Herpes virus called T-VEC , was used to treat skin cancer.

Usually, such experimental therapies are tested only in patients who are in advanced stages of the disease. Dr. Halassy’s case In the case of Dr.

Halassy, she was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 2016 and underwent chemotherapy and a mastectomy (breast removal surgery). In 2018, at the site of the mastectomy, the cancer reappeared, and she underwent a minor surgery once again. In 2020, when she realised that the cancer had recurred for the second time, she decided to try the unconventional method of using viruses to treat her cancer.

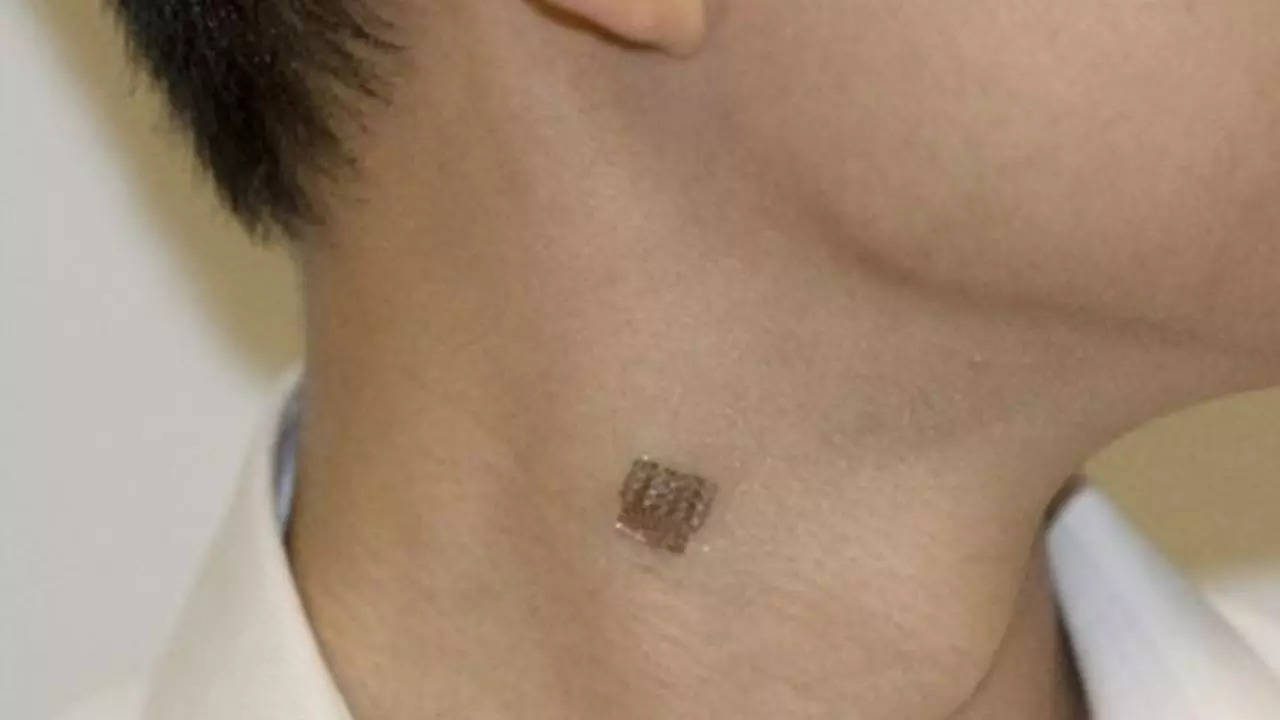

Being a virologist herself, the treatment was carried out using viruses grown in her own laboratory at the University of Zagreb, Croatia. For her treatment, she chose the measles and vesicular stomatitis viruses. The measles virus was picked because breast cancer cells are known to express two proteins called CD46 and nectin-4 on their cell surface in abundance.

Since the measles virus uses these proteins to enter the cells, and a safe strain of the virus was already available and being used as a vaccine, it was the ideal choice. Vesicular Stomatitis virus, on the other hand was chosen because of its low pathogenicity to humans , and the results of a previous study that demonstrated its effect on breast tumours in mice. The authors report that upon administration of this treatment, the tumour shrank in two months, allowing its surgical removal, and Dr.

Halassy has been cancer-free for almost four years. The authors conclude in their manuscript, that their work supports the possibility that this technique can be used to treat patients at earlier stages of cancers. While the work does indeed holds promise for future cancer treatments, that potential does little to overshadow the glaring problem in Dr.

Halassy’s research. The dangers of experimenting on oneself Experimenting on oneself is a deeply dangerous practice. Whilst it is true that the act requires a certain degree of bravery and a firm belief in the underlying science, it comes at the inevitable cost of losing objectivity in the research.

This introduces a bias in the interpretation of results, and, at the very least, undermines the rigour necessary to draw meaningful conclusions from data. For instance, in Dr. Halassy’s case, she obviously wanted the treatment to succeed, since even the most favourable among the alternatives – that of the treatment having no effect, meant she still had to deal with cancer itself.

The worst outcome was an adverse reaction to the two viruses that were injected, with a chance, albeit very small, of death itself. This means, naturally, that she cannot be an unbiased judge of the procedure since she has a stake in the outcome. While one can certainly argue that by being a virologist herself, she was better informed about the underlying risks than any other patient, and, that she was well within her rights to do it on herself, it still does not justify bypassing the ethical standards and safeguards that protect scientific research.

This is because, Dr. Halassy’s work sets a dangerous precedent — one where less-qualified scientists might take to experimenting on themselves without fully understanding the risks involved. Such actions could set the field back significantly, as any mishap would likely lead to months, or even years, of debate before new guidelines could be established to ensure safety standards.

Ironically, in her own paper, Dr. Halassy herself cautions against the use of vesicular stomatitis virus in future studies due to reports of its neurological effects on mice. Self-experimentation has, in the past, resulted in results at both extremes of the spectrum.

It has led to scientific glory, as was the case with Barry Marshal , who drank a flask containing the bacterium Helicobacter pylori to demonstrate that it is the causative agent of peptic ulcers, leading to his Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2005. It has also lead to tragedy, like Jesse Lazear, who, in 1900, allowed himself to be bitten by infected mosquitoes to show that yellow fever is transmitted by them, resulting in his death. While Dr.

Halassy has certainly escaped the latter eventuality, whether her actions will lead her to the former, only time will tell. (Arun Panchapakesan is an assistant professor at the Y.R.

Gaithonde Centre for AIDS Research and Education, Chennai. arun.panchapakesan@gmail.

com) Published - November 21, 2024 04:00 pm IST Copy link Email Facebook Twitter Telegram LinkedIn WhatsApp Reddit health / medical research / healthcare policy / cancer / non-communicable diseases / ethics.