Diagnosing endometriosis is often delayed, sometimes by as much as 12 years after symptoms begin. This is due to factors like the normalization of menstrual pain, the need for invasive diagnostic surgery, limited understanding of the condition’s complexity, and frequent misdiagnoses. Conventional treatments often fall short because they do not address the whole-body nature of endometriosis.

Effective management requires an integrated, personalized approach. Chronic pelvic or lower abdominal pain: Often the most prominent symptom leading women to seek medical care. This pain may be constant or cyclical and is often worse during menstruation.

Painful periods (dysmenorrhea): Severe menstrual cramps that may begin before and extend several days into the menstrual period Back pain: Lower back pain is common, often occurring along with pelvic pain or menstruation. Heavy or irregular periods: Heavier than normal menstrual flow, bleeding between periods, or more frequent cycles Pain with sex: Deep pain during or after sexual intercourse Urinary symptoms: Pain with bladder filling or urination, or increased urinary frequency, especially during menstruation Painful bowel movements: Discomfort or pain during bowel movements, often with diarrhea, constipation, or bloating, especially during menstruation Fatigue: Chronic fatigue, often worse during menstruation Infertility: Affects 20 to 30 percent of all women with infertility The Essential Guide to Breast Cancer: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments, and Natural Approaches The Essential Guide to Osteoporosis: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments, and Natural Approaches Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments, and Natural Approaches Origins of Endometrial-like Cells Being present at birth —occurring during fetal development Retrograde menstruation— occurs when menstrual blood flows backward into the pelvic cavity, carrying endometrial cells with it. This process is not unusual and happens in 90 percent of women.

Spreading— through the lymphatic system or blood vessels Metaplasia —a process where cells change and become endometrial-like cells outside the uterus. Hormones and Immune Dysfunction in Lesion Formation Normally, the immune system would remove these misplaced cells, but in endometriosis, it malfunctions and activates them instead. Driven by estrogen, the immune system helps the cells stick to tissues and grow by forming their own blood supply and nerve connections.

Pain and Nervous System Remodeling Painful Periods and Infertility in Endometriosis Chronic inflammation: Pelvic lesions cause inflammation that leads to cramping and pain during menstruation. Disruption of reproductive processes: Inflammation can affect egg development, ovulation, and fertilization. Structural changes: Lesions and scar tissue can change the structure of pelvic organs, blocking fallopian tubes or hindering egg movement.

Hormonal imbalances and pain-inducing chemicals: Endometriosis can cause hormonal imbalances and release chemicals like prostaglandins, which intensify period pain and interfere with embryo implantation in the uterus. The Role of Microbiomes in Endometriosis Genetic and Epigenetic Factors Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) Dioxins: Found in fatty foods such as meat, dairy, and fish, industrial sites, and smoke from burning plastics or treated wood, these persistent organic pollutants are linked to an increased risk of endometriosis. Organochlorines: Used in pesticides , some, but not all, studies link organochlorines to endometriosis.

Organochlorines are found in contaminated soil, water, and fatty foods. Phthalates: Used in plastics , food packaging, vinyl flooring, cosmetics, personal care products, and some toys. Some studies link phthalates to endometriosis though results vary.

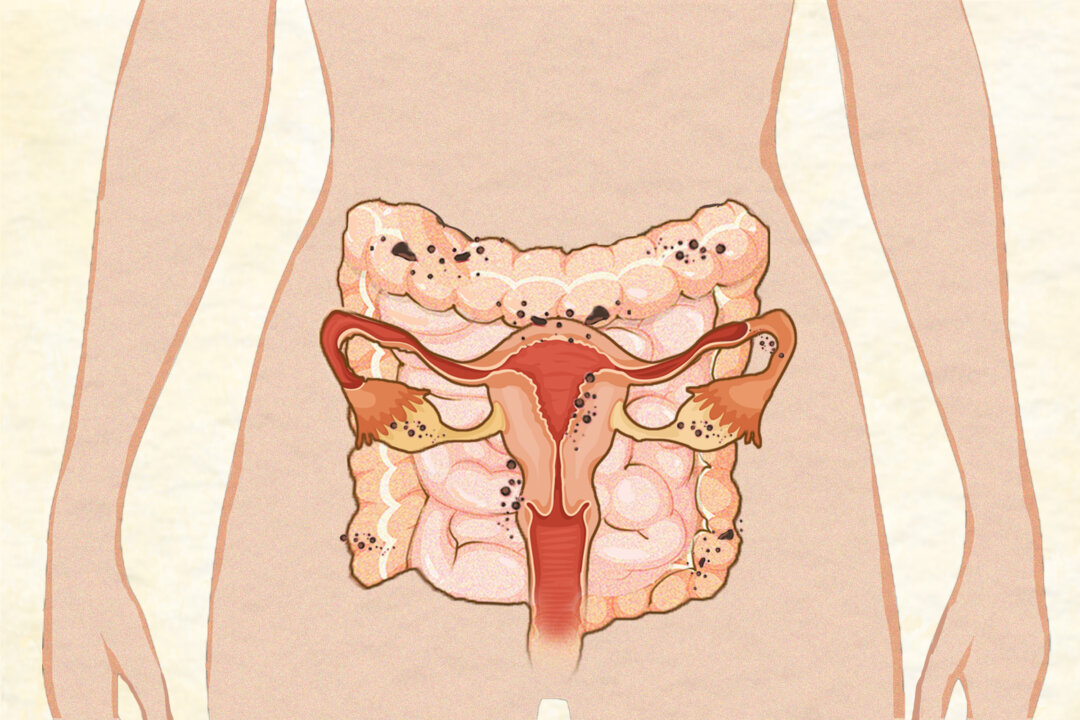

Bisphenol A (BPA): A plastic component with estrogen-like properties, BPA is found in food containers, can linings, dental sealants, and cash register receipts. Superficial peritoneal endometriosis: Lesions form on the pelvic peritoneum (the thin lining inside the pelvis) and account for 15 to 50 percent of cases. Ovarian endometrioma: Ovarian cysts present in 2 to 10 percent of cases and 50 percent of those with infertility.

Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Lesions grow into tissues and organs behind the abdominal lining, such as the vagina, bladder, and bowel. This type occurs in 20 percent of cases, with bowel involvement in 5 to 12 percent. Stage I: mild (AFS) or minimal (ASRM) Stage II: moderate (AFS) or mild (ASRM) Stage III: severe (AFS) or moderate (ASRM) Stage IV: extensive (AFS) or severe (ASRM) Sex: Endometriosis primarily affects females or those born female with intact female reproductive organs.

Rare cases have been reported in men, possibly due to residual tissue from fetal development. Age: The highest risk is in women aged 25 to 45, though it can also occur in 2 to 5 percent of postmenopausal women, adolescents after menstruation begins, and rarely, in girls before their first period. Menstrual and reproductive history: Early onset of periods and short menstrual cycles increase risk, likely due to higher circulating estrogens.

Having given birth and using oral contraceptives are linked to a lower risk. Ethnicity: Endometriosis may be more common in women of Asian descent and less common in women of African and Hispanic descent, though further research is needed to confirm whether these differences are biological, due to sociocultural factors, or access to health care. Family history: Having a first-degree relative with endometriosis increases a woman’s risk up to sevenfold .

Omega-6 fatty acids: Inflammatory omega-6 fatty acids may increase risk. Conversely, higher intake of omega-3 fatty acids is associated with reduced risk, likely due to anti-inflammatory effects. Body mass index (BMI): Some studies suggest both high BMI (over 30) and low BMI may increase the risk.

Obese women often report more severe menstrual pain, possibly because body fat produces estrogen and inflammation-causing substances. Alcohol: Research shows mixed findings, with some studies indicating increased risk and others showing no effect. A higher risk is noted with more than three drinks per week, possibly due to alcohol’s impact on estrogen levels and inflammation.

Caffeine: Studies on caffeine’s effects on endometriosis are also mixed. Some show no effect, while one suggests a potential link, particularly with coffee intake above 300 milligrams of caffeine per day, which is 16 ounces for some brands. Regular exercise: Findings vary depending on the type of exercise.

However, doing aerobic exercise three or more times a week and strength training twice a week may lower the risk of endometriosis by 40 to 80 percent. Prolonged sitting: Long periods of sitting are associated with an increased risk. Night work: Working rotating night shifts for five years or more raises risk.

Abuse: Those who have experienced physical and sexual abuse are more likely to develop endometriosis. Doctors usually order basic blood tests, such as a complete blood count with differential, to rule out other conditions and check for anemia, which is common in women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Despite research on inflammatory and immune markers and the microbiome, no biomarkers have been approved to diagnose endometriosis.

Imaging tests like ultrasound and MRI cannot reliably detect small or superficial lesions, so a definitive diagnosis requires microscopic evaluation of a biopsy obtained surgically. Functional Medicine Testing Environmental toxicity screen: Detects toxins or endocrine disruptors that may cause hormonal imbalances or inflammation. Heavy metals assessment: Identifies toxic metal accumulation that could affect immune function and health.

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) breath test: Ordered if gastrointestinal symptoms are present, given the link between irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), SIBO , and endometriosis. Comprehensive stool analysis: Provides detailed information about gut health, including microbial composition, parasites, and markers for digestion, inflammation, and intestinal permeability. Vaginal microbiome assessment: Evaluates vaginal microbial composition or pH levels to identify dysbiosis.

Vaginal pH of 4.5 or above may indicate an issue. Hormone and metabolites panel: Assesses hormonal imbalances and estrogen metabolites to understand estrogen processing.

Inflammatory markers tests: Tests like C-reactive protein and Galectin-3 evaluate inflammation and scarring risks. Other possible tests: May include food allergy and sensitivity panels, celiac and gluten sensitivity evaluation, nutrient levels, and omega fatty acids. Decreased quality of life, affecting social, emotional, and sexual well-being Anatomical abnormalities from adhesions Organ dysfunction (e.

g., bowel or bladder) Infertility or subfertility Ovarian cancer (associated with ovarian endometriomas) Reduced work productivity and physical activity Poor sleep quality Pregnancy complications, such as miscarriage, preterm birth, bleeding, placental issues, fetal growth restriction, high blood pressure, and cesarean delivery. Surgery can increase pregnancy rates by up to 60 percent in cases of infertility, but it does not stop endometriosis from progressing.

The condition returns in 20 to 30 percent of individuals within five years, and about 36 percent require additional surgeries. Endometriosis can also come back after a hysterectomy. Comprehensive care should be personalized and involve a multidisciplinary team.

Conventional treatments include: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs and antagonists: Induce a low-estrogen state to alleviate symptoms Aromatase inhibitors: Lower estrogen levels Oral contraceptives: Regulate hormones to reduce pain and bleeding Progestins (dienogest, norethindrone acetate, medroxyprogesterone): Synthetic progesterone to reduce pain and slow endometriosis growth. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Manage pain and inflammation Acetaminophen: Pain relief Opioids: Severe pain management Laparoscopic excision: Removes entire lesions, including deeper tissue, for better long-term results. Limited access to skilled surgeons and insurance coverage can be challenging.

Laparoscopic ablation: Destroys lesions using heat or laser. Hysterectomy: Removes part or all of the uterus, sometimes including ovaries. Integrative Treatments Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM): Small studies suggest TCM, including herbal medicine, acupuncture, enemas, and external applications, can achieve effectiveness rates of 90 percent or higher in relieving symptoms like dysmenorrhea and infertility.

Some herbal treatments promote lesion regression with few side effects and long-lasting benefits by enhancing blood circulation and removing stasis. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS): Uses electrical stimulation on the skin to relieve pain. Evidence suggests it may reduce chronic pelvic pain and pain during intercourse, improving quality of life.

TENS is considered safe with minimal side effects when used properly. Cannabis: Some women with endometriosis and researchers report cannabis is effective for pain relief due to its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. Research on its long-term use and overall effectiveness is ongoing.

Low dose naltrexone (LDN): Originally used to treat addiction, LDN at lower doses is recognized for its potential as an immunomodulator , anti-inflammatory, and pain reliever. While specific research on endometriosis is lacking, its ability to regulate immune function in other conditions suggests it could be a helpful treatment, warranting further study. Emerging Treatments Immunomodulators: Target immune system components like macrophages, NK cells, and T cell responses, but human trial benefits are limited so far.

Anti-angiogenic agents: Aim to prevent new blood vessel growth to reduce lesion development and spread. Mind-body practices, like yoga and meditation, can improve the quality of life and well-being of women with endometriosis. Some women feel insecure about their bodies due to symptoms or treatments, which can lead to disordered eating.

Hatha yoga specifically can help boost self-image, potentially reducing the risk of disordered eating. Dietary Foundations for Managing Endometriosis Fiber: Aim for at least 25 grams daily to help reduce circulating estrogen levels and feed beneficial gut bacteria. Sources include vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains.

Fat: Limit trans fats and conventionally raised red meat; increase omega-3 fatty acids from fish and plant sources such as flaxseeds, chia seeds, and walnuts. Gluten: Consider gluten elimination as it can increase intestinal permeability . Although studies on endometriosis are conflicting, one study found that 75 percent of women with endometriosis reported less pain after removing gluten.

Macronutrient balance: Eat balanced meals with complex carbohydrates, lean proteins, and healthy fats to help stabilize blood sugar levels. Metabolic syndrome , which includes high blood sugar, is linked to endometriosis and may worsen inflammation and hormonal imbalances. Anti-inflammatory foods: Include turmeric, ginger, berries, leafy greens, fatty fish like salmon, nuts (especially walnuts), and olive oil to help reduce inflammation.

Antioxidants: Prioritize antioxidant-rich foods to counter oxidative stress. Colorful fruits and vegetables offer antioxidant benefits as well as essential fiber and anti-inflammatory polyphenols . Good sources include citrus fruits, berries, leafy greens, nuts, and seeds.

Cruciferous vegetables: Vegetables like broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, and kale, contain indole-3-carbinol, which supports detoxification and a healthier balance of estrogens in the body. They also provide sulforaphane , which helps reduce inflammation and supports cellular health. Targeted Elimination Diets Elimination diet: This approach involves removing common inflammatory foods like dairy, gluten, soy, eggs, and red meat for a period of time, typically four to six weeks.

Foods are then reintroduced one at a time while watching for symptoms. This can help identify individual food sensitivities that may be exacerbating endometriosis symptoms. Low-FODMAP diet: FODMAPs are fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols.

These fermentable carbohydrates can cause digestive symptoms. Examples of high-FODMAP foods include wheat, dairy, onions, and beans. For women with endometriosis who also have IBS, a low-FODMAP diet may help reduce bloating, gas, and abdominal pain.

The diet involves avoiding high-FODMAP foods for several weeks, then slowly reintroducing them to identify triggers. Autoimmune protocol (AIP) diet: A stricter form of the Paleo diet, the AIP diet aims to reduce inflammation and support gut health by cutting out grains, legumes, dairy, eggs, nightshades, nuts, seeds, and processed foods. While not specifically studied for endometriosis, it has been shown to reduce inflammation and modulate the immune system in women with Hashimoto’s and to reduce inflammation and achieve remission in inflammatory bowel disease .

Gut Health, Immunity, and Inflammation Management L-glutamine-rich foods: Spinach, cabbage, and grass-fed beef Zinc sources: Oysters, beef, pumpkin seeds, and lentils Omega-3 fatty acids: Fatty fish (salmon, sardines), chia seeds, and walnuts Fermented foods: Sauerkraut, kimchi, and kefir to enhance microbiome diversity Prebiotic foods: Garlic, onions, asparagus, and bananas to nourish beneficial gut bacteria Red Meat Supplements Resveratrol Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) Curcumin Extracts of Pueraria (kudzu flower), black garlic, Calligonum comosum, and Uncaria tomentosa (cat’s claw) Melatonin Modified citrus pectin Key Lifestyle Strategies for Managing Endometriosis Exercise: Regular exercise such as walking, yoga, and strength training, can reduce inflammation, insulin resistance, and pain related to endometriosis. Frequency and consistency are key for therapeutic benefits. Moderate exercise is recommended because high-intensity exercise may be linked to reproductive disorders.

Stress: Stress can worsen endometriosis symptoms by suppressing immune function, increasing inflammation, and disrupting hormonal balance, which can lead to more severe lesions. Reducing stress can help ease pain and support healing. Sleep: Circadian rhythms regulate hormones affecting sleep, immune function, and inflammation.

Poor sleep disrupts these rhythms, causing hormonal imbalances and increased inflammation. Keeping a regular sleep schedule, getting natural light, and limiting blue light exposure can support healthy rhythms. While you may not be able to completely prevent endometriosis, certain lifestyle changes can help manage inflammation, oxidative stress, and estrogen levels.

These changes might reduce the risk and ease symptoms. They could also affect gene expression, impacting your health and possibly the health of future generations. Exercise regularly to maintain a healthy weight, manage pain, and balance estrogen levels.

Follow the dietary principles discussed in the natural approaches section to manage inflammation and balance hormones. Maintain a healthy gut lining and microbiome to support immune function and reduce inflammation. Limit or avoid alcohol and caffeine to help lower estrogen production.

Choose organic foods when possible and use chemical-free cleaning products and personal care items to reduce toxic exposures. Use glass or stainless steel containers for food storage , avoid heating food in plastic containers, and avoid non-stick cookware to minimize exposure to harmful chemicals. Consider professional counseling if you have a history of trauma, such as physical or sexual abuse.

Practice at least ten minutes of deep breathing daily to help reset the stress response. Regularly engage in activities that bring joy and relaxation to support overall health and resilience..