T oday, when I watch the latest news on international channels about Israel’s shelling of hospitals, schools, houses in Gaza and civilian targets in Beirut, I recall a German play on the Holocaust during the European Theatre Week organised two decades ago at the Alhamra Arts Centre in Lahore. Its dialogue, props and acting revolved around the calculated extermination of Jews by the Nazis. Since the play featured a single performer, the plight of the Jews (their death by gassing) was represented through used frocks, shirts and pairs of shoes scattered around the stage.

T-shirts, trousers, frocks, shawls, shirts and shoes are also scattered every day across the electronic and print media, reporting the strategic destruction, eradication and annihilation of Palestinians — most of them children, mothers and the elderly — none of whom are responsible for or accomplices in last October’s debacle. The genocide of the innocent of Gaza by a nation that was itself once the victim of another power is now transmitted in the form of blood-stained shoes, torn clothes and broken belongings. A tragedy is unfolding on a scale far larger and more real than what was portrayed by the unnamed actor and director of that drama in Lahore.

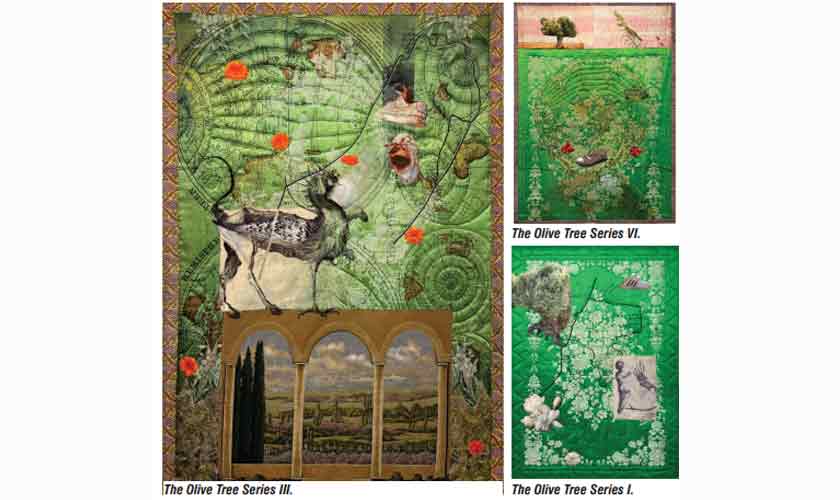

Shoes appear in almost every work of Risham Syed from her solo exhibition Chait Vasraand (what the rain remembers), being held from November 19–28 at Canvas Gallery, Karachi. Alongside footwear of different sizes, designs and degrees of wear, one encounters a range of images stitched – both physically and in printed layers – onto vintage Chinese jacquard silk panels inherited by the artist from her late mother. In previous years, Syed has created mixed media images with tapestry, typically installed against walls or suspended in space.

However, in her current show, the display of large fabric pieces (72 x 52 inches each) placed on the gallery floor expands the meaning and context of two key pictorial motifs: shoes and maps. Shoes, which provide a protective layer for human feet, are typically connected to the ground – rooted in territory, arguably more so than humans themselves. They also serve as an outer skin, traditionally made of animal hide.

A pair of shoes, in the absence of their owner or wearer, holds and rekindles the memory of that person – much like the abandoned boots, sandals, slippers and sneakers seen among the rubble of schools, hospitals and apartments destroyed by Israeli fighter planes in Gaza. The other element connected to the land is the map. It serves as a minimised – but meticulously measured — substitute for a terrain rendered on a sheet of paper, a piece of vellum carved into stone, etched onto metal, or wrapped around a sphere.

In Risham Syed’s artworks, the outlines of the world are either stitched with threads and needles, printed on fabric, or both. In some pieces, multiple cartographies overlap, preserving a diversity of geography, perception and precision within a single image. An important feature of maps, regardless of their time, location or scale, is their sense of orientation.

A map has a centre – whether it represents the centre of the earth, the universe, a city, a neighbourhood, or a building complex. That central point is directed towards the maker or user, aligning with their body, beliefs, residential address, or current position (as seen in large plaza maps with an arrow stating, “You are here”). This navel delineates a specific context – of being or being at the centre of the entire world: the shopper in a mall, a structure like the Kaaba for Muslim communities, or a city like Jerusalem for Christians and Jews, especially in maps created during the Middle Ages.

The situation has not changed much, as the state of that city and its surrounding areas remains a global concern due to Israel’s ongoing airstrikes and ground attacks. In Risham Syed’s new work, one observes the map of (undivided) Palestine inscribed in the centre of a rectangular composition, occasionally marked with red spots, splashes and strokes. These visuals, with their complexity of pictorial construction, evoke medieval maps, particularly the Catalan Atlas created by Abraham Cresques in 1377 CE on vellum.

This world map, much like the Google Maps of the Twenty-First Century, can be viewed from all sides rather than as a fixed, upside-down image and is most effectively observed when laid flat on a table—similar to Syed’s display choices for her works in the current exhibition. Usually, we consider a map to be a factual document of distances, places and directions, drawn as a diagram of simplified, stylised and geometric shapes. However, Google Maps on our smart-phones not only provide a detailed plan of an area but also offers elevation views, traffic updates, estimated travel times based on various modes of transportation and alternative route options.

This functionality parallels medieval maps, which included not only places and paths but also travellers, local inhabitants and elements from different eras of history. These maps did more than “provide outlines of countries and features in the landscape.” Like the Catalan Atlas , they combined “a mixture of myth, history, and stories reported by early travellers,” making them both functional and richly narrative.

In Risham Syed’s creations, one discovers a blend of the present and the past—not merely an observation but a commentary on what is unfolding in our milieu. In each part of The Olive Tree Series , the artist, as she states, has assembled “fragments of memory, testimony, and resilience. Imbued with the weight of history, these fragments witness the human capacity for endurance.

” These seven mixed-media tapestry panels reference the loss of human life, lands (Palestine and the world — first known and then captured in maps), real and fantastical fauna, red flowers, pomegranates, historic documentation of European cities, snippets of landscapes, floral patterns, smears of red colour and the inescapable presence of China (visible in the material and fabrication of every surface). If the olive tree in the title of this body of work refers to the ancient land of Palestine, it also emphasises the urgency of peace in that tormented territory. As an artist who, in the past – particularly for her project that won the Abraaj Capital Art Prize in 2012 – conducted extensive research on colonisation, the manipulation of human labour and the unjust cartography of trade, Risham Syed observes that political cruelty is inherently linked to economic exploitation.

This connection has historically led to wars, conflicts and bloodshed. It now manifests in the contemporary occupation of natural resources, market control and the proliferation of arms production. What elevates Risham Syed’s work beyond being purely political and analytical is her innate ability to transform facts into fiction without distorting their truth.

The introduction of poetic language, steeped in tradition, invites viewers to enter these worlds. Emerging from maps to real locations, these narratives reflect events that are not merely transient but form memories capable of outliving death. The writer is an art critic, curator and a professor at the School of Visual Arts and Design, Beaconhouse National University, Lahore.