For more than four years since 2020, Filipino journalist Frenchie Mae Cumpio has been languishing in a Tacloban City jail, with the first hearing conducted in June of that year and, after long pauses, the latest held last Monday, Nov. 11, 2024. It has been a long campaign for the release of this young community journalist who served as the executive director of the online news group Eastern Vista and radio anchor of Lingganay han Kamatuoran (Bells of Truth) that aired over Aksyon Radyo Tacloban DYVL 819.

Eastern Vista is affiliated with AlterMidya network. Last Monday, Gabriela Women’s party Rep. Arlene Brosas delivered a privilege speech in Congress calling for Cumpio’s immediate release and speedy trial.

Brosas said Cumpio’s absence “left a void in the community’s access to critical information, a void that we fear is now being filled with disinformation and cripples the people’s participation in governance and society.” Cumpio, along with four others, were arrested on Feb. 7, 2020 during a pre-dawn raid on their apartment by the Philippine National Police and Armed Forces operatives.

This was during the Rodrigo Duterte presidency when “Red-tagging” of anti-government critics (suspected communist sympathizers) was the order of the day and a task force was created to silence dissent and sow fear. The charges against Cumpio, et al. (known as the “Tacloban 5”): illegal possession of firearms and explosives and the nonbailable offense of “terrorist financing” under Republic Act No.

10168. Cumpio’s lawyers called the illegal possession of firearms charge as a way to “justify the illegal arrest.” The cases, Brosas decried, have moved at a slow pace “due in no small part to the delaying tactics of the prosecution.

” The campaign to speed up the handling of the cases has gone through government institutions, including the Commission on Human Rights and the Office of the Ombudsman, but sadly, the quest for justice is fraught with delays. Terrorism financing, a fancy byword in the Duterte government’s anti-terrorism campaign, means financially aiding the enemy, or what else could it be? But who is a terrorist and who is not? During the raid and arrest of the Tacloban 5, a reported amount of money (half a million pesos plus) was found, an aggravating matter, indeed, in the eyes of the raiders. If seized or planted firearms can make one a terrorist, seized cash and proofs of cash deposits can easily make one a terrorist financier? The Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) has come into the picture by initiating a “civil forfeiture” case related to the terrorism financing charges, AlterMidya said.

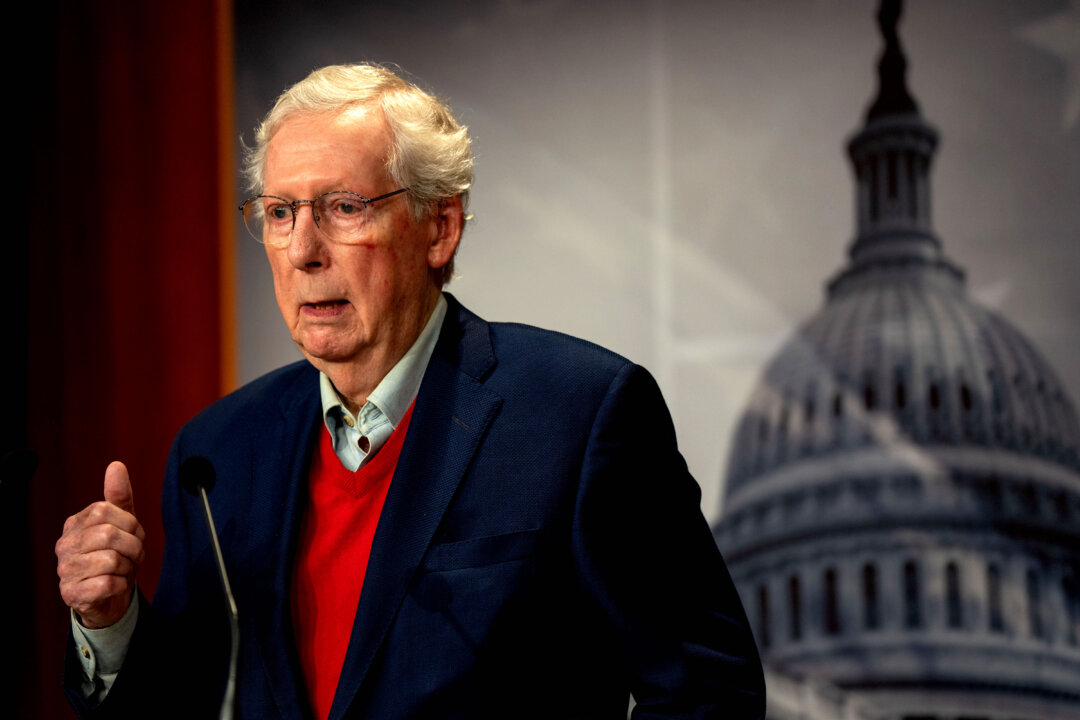

With AMLC’s freezing of assets of suspected so-called “terrorism financiers,” one fears that it is becoming more weaponized against nongovernment and people’s organizations as in the case of the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines’ frozen bank account. The big-time money launderers are able to get away. According to the 2023 Global Prison Census of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Cumpio remains to be the only journalist behind bars in the Philippines, an added black eye on the Philippines’ record of media workers killed.

What had Cumpio done to deserve her prison ordeal? She is only in her mid-twenties. Cumpio had been covering police and military matters and abuses as well. Before her arrest, she had experienced harassment and intimidation, a throwback to the dark years of martial rule under the Marcos dictatorship when journalists lived in a climate of fear but fought back anyway with the power of the word.

And paid dearly for it. The CPJ fears that if Cumpio “is convicted of illegally possessing firearms, [she] could face six to 12 years in prison, according to the Philippine law governing firearms and ammunition. If convicted under Section 8 and other provisions related to terrorism financing of the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020, she faces a maximum of 40 years in prison as defined by ‘reclusion perpetua’ penalties.

” Early this year, a United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression in the person of Irene Khan, visited Cumpio and her co-accused at the Tacloban City Jail. Khan saw the need for a reassessment of the treatment of journalists in the Philippines and its chilling effect on truth-tellers and communicators. We all know that hereabouts a hired assassin simply enters the broadcast booth and fires as in the case of broadcaster Percy Lapid in 2022.

With 204 documented murders of journalists since 1986 when democracy was restored, the Philippines is at a miserable 134th ranking out of 180 in the Reporters Without Borders’ 2024 World Press Freedom Index. There is more to the Cumpio, et al. case than meets the eye.

Community journalists, vulnerable that they are, are in the front lines of news reporting, especially in remote areas. They are in the line of fire. I, as a working journalist who had been in the trenches, know what it is like.

May Frenchie Mae Cumpio not lose heart. Subscribe to our daily newsletter By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

—————- Send feedback to [email protected].