The Westminster form of government is based on the principle of collective responsibility. All ministers being bound by the collective decisions of the cabinet bear a joint responsibility for all policies and decisions of the government. This means that a decision of the cabinet or a cabinet committee is binding on all members of the cabinet regardless of whether any of them voiced different views or was absent from the meeting.

According to the "Cabinet Manual" of the UK government, all ministers are bound by the collective decisions of the cabinet, save where it is explicitly set aside, and carry joint responsibility for the government's policies and decisions (4.2). The "Ministerial Code" of the UK government also states that the principle of collective responsibility, save where it is explicitly set aside, requires that ministers should be able to express their views frankly in the expectation that they can argue freely in private while maintaining a united front when decisions have been reached.

This, in turn, requires that the privacy of opinions expressed in cabinet and ministerial committees, including in correspondence, should be maintained (2.1). It may be relevant to refer to what Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, said in this regard: a government in the parliamentary model is one united whole.

It has a joint responsibility. Each member of the government must support others so long as he remains in the government. It is quite absurd for any minister to oppose or give the impression of opposing his colleague.

Opinions may be freely expressed within the cabinet. Outside, the government should have only one opinion. It may be noted that the constitutional and legal framework of Bangladesh, as of now, is conducive to the concept of collective responsibility.

Bangladesh is a parliamentary democracy where the cabinet is collectively responsible to parliament [Article 55(3) of the constitution]. According to Rule 159 of the "Rules of Procedure of Parliament," a no-confidence motion can be moved against the cabinet, not against any individual minister. The "Rules of Business," 1996, made by the president under Article 55(6) of the constitution, provides instructions about the allocation and transaction of business in the government and also specifies the coordination and consultation mechanisms in the government.

These are further elaborated in the "Secretariat Instructions" (amended up to 2014) issued by the Ministry of Public Administration under the authority given in the "Rules of Business." While we look forward to significant changes in the existing constitutional and legal provisions on the basis of the recommendations made by the Constitutional Reforms Commission set up by the interim government, it is very likely that the Westminster model of government will continue with necessary provisions for de-concentrating of power as well as adequate checks and balances. Experiences suggest that although we had a Westminster model of government in books, it was a prime ministerial system of government in practice, as many would argue, and not a cabinet or parliamentary form.

It was customary for the chief executive of the government to make critical decisions individually instead of jointly by the cabinet. The existing provisions for in-depth consultations with relevant stakeholders from within and outside the government were also not properly followed. In this situation, in many cases, they were hardly collective decisions, and in the absence of collective decisions, the concept of "collective responsibility" becomes irrelevant.

It is also interesting to note how members of the same cabinet occasionally spoke in public on important policy issues very differently. "Rules of Business" provides that ministers shall act as official spokesmen of the government in respect of their ministries. Secretaries and other government-authorised officers may also act as official spokesmen.

No statement involving foreign policy shall normally be made by a person other than the prime minister and the foreign minister without prior consultation with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs [Rule 28 (4)]. However, we have noticed multiple ministers making public statements on issues with serious foreign policy implications, sometimes in an inconsistent manner. The concept of collective responsibility does in no way waive the minister's personal responsibility with respect to leading his or her own ministry.

According to the "Cabinet Manual" mentioned earlier, ministers remain accountable to the parliament for decisions made under their powers. The "Ministerial Code" of the UK government further elaborates that the minister in charge of a department is solely accountable to parliament for the exercise of powers on which the administration of that department depends. Bangladesh's "Rules of Business" also states that subject to other relevant provisions, all business allocated to a ministry/division shall be disposed of by, or under the general directives of the minister-in-charge.

The minister shall also be responsible for conducting the business of his ministry/division in the parliament. As administrative head and principal accounting officer of the ministry/division, the secretary is responsible for careful observance of relevant rules and regulations with regard to administrative and financial matters. The secretary is also required to keep the minister informed of the workings of the ministry/division [Rule 4].

It may be noted that a minister cannot disown the stance of his ministry with regard to important policy or executive decisions. He cannot be bypassed in submitting a proposal to the cabinet or the prime minister. The standard last paragraph of a summary for the cabinet or a cabinet committee is, "The minister in charge of the Ministry X has seen the summary, approved it, and given his consent to send it to the Cabinet Division for consideration of the Cabinet/Cabinet Committee on Y" and signed by the secretary.

Summaries to the president and the prime minister are also submitted through the minister. The idea of a minister's individual responsibility occasionally raises scepticism mainly on two grounds. First, whether a minister can be held responsible for any failure or mistake given that in a Westminster model, government decisions entail collective responsibility.

In this context, one needs to differentiate between the decisions made by the cabinet and by the line ministry. The "Rules of Business" categorically mentions that no important policy decision shall be taken except with the approval of the cabinet [Rule 4]. It also provides an indicative list of cases that should be brought before the cabinet [Rule 16].

Other matters are decided by the respective ministries for which the minister is responsible. Here comes the second reason for being sceptical about the minister's individual responsibility. In reality, a minister is not involved in deciding on each and every case.

Much of the authority in a ministry is delegated to various levels of the bureaucracy. In this context, how can a minister be held responsible for an action taken without his approval or even knowledge? Whether a minister should step down, taking responsibility for the fault of his colleagues, is an old, unsettled question. Where a wrong action has been taken by a civil servant that the minister disapproves of and has no prior knowledge of, he is still responsible to parliament for the fact that something has gone wrong in the ministry or department, and he alone can tell parliament what happened.

In 1954, the UK Minister for Agriculture, Sir Thomas Dugdale, told the House of Commons, "I, as a minister, must accept full responsibility to Parliament for any mistakes and inefficiency of officials in my department, just as, when my officials bring off any successes on my behalf, I take full credit for them." The minister chose to step down, although the prime minister defended him. According to the UK "Cabinet Manual," civil servants are servants of the Crown.

The civil service supports the government of the day in developing and implementing its policies and delivering public services. Civil servants are accountable to ministers, who in turn are accountable to parliament (7.1).

The manual further states that ministers also have a duty to give fair consideration and due weight to informed and impartial advice from civil servants, as well as to other considerations and advice in reaching policy decisions (7.2). The same provisions are echoed in the UK "Ministerial Code" (5.

1, 5.2), which also defines the role of heads of departments and the chief executives of executive departments who are appointed as accounting officers (5.3, 5.

4, 5.5). This is similar to the provisions for the secretaries acting as principal accounting officers in Bangladesh's "Rules of Business.

" The introspection of Sir Winston Churchill, the British prime minister during the Second World War, about the fall of Singapore to the Japanese forces is still useful in understanding responsibility in the context of government. He wrote, "I ought to have known, my advisers ought to have known, and I ought to have been told, and I ought to have asked." The primary responsibility for a wrong decision or action lies with concerned officials, but the ultimate responsibility goes to the political leadership.

While officials have a responsibility to provide proper advice proactively, the leadership needs to seek advice from those who know the matter. This explains why the UK "Cabinet Manual" and "Ministerial Code" attach so much importance to acting on informed advice. In the Westminster system, the collective responsibility of the cabinet is critically important for making coherent and integrated policies and their effective implementation.

It also helps mitigate the excessive concentration of power in the hands of the chief executive and makes the decision-making process more participatory and inclusive. This holistic approach is strengthened by individual ministerial responsibility and bureaucratic accountability. Wider and deeper consultations with stakeholders are crucial for the system to perform better.

Eventually, they become instrumental for public institutions to fulfil the government's obligations to the citizens. M Musharraf Hossain Bhuiyan is former cabinet secretary, Government of Bangladesh, and currently serving as senior adviser at the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD). Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission. The Westminster form of government is based on the principle of collective responsibility.

All ministers being bound by the collective decisions of the cabinet bear a joint responsibility for all policies and decisions of the government. This means that a decision of the cabinet or a cabinet committee is binding on all members of the cabinet regardless of whether any of them voiced different views or was absent from the meeting. According to the "Cabinet Manual" of the UK government, all ministers are bound by the collective decisions of the cabinet, save where it is explicitly set aside, and carry joint responsibility for the government's policies and decisions (4.

2). The "Ministerial Code" of the UK government also states that the principle of collective responsibility, save where it is explicitly set aside, requires that ministers should be able to express their views frankly in the expectation that they can argue freely in private while maintaining a united front when decisions have been reached. This, in turn, requires that the privacy of opinions expressed in cabinet and ministerial committees, including in correspondence, should be maintained (2.

1). It may be relevant to refer to what Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, said in this regard: a government in the parliamentary model is one united whole. It has a joint responsibility.

Each member of the government must support others so long as he remains in the government. It is quite absurd for any minister to oppose or give the impression of opposing his colleague. Opinions may be freely expressed within the cabinet.

Outside, the government should have only one opinion. It may be noted that the constitutional and legal framework of Bangladesh, as of now, is conducive to the concept of collective responsibility. Bangladesh is a parliamentary democracy where the cabinet is collectively responsible to parliament [Article 55(3) of the constitution].

According to Rule 159 of the "Rules of Procedure of Parliament," a no-confidence motion can be moved against the cabinet, not against any individual minister. The "Rules of Business," 1996, made by the president under Article 55(6) of the constitution, provides instructions about the allocation and transaction of business in the government and also specifies the coordination and consultation mechanisms in the government. These are further elaborated in the "Secretariat Instructions" (amended up to 2014) issued by the Ministry of Public Administration under the authority given in the "Rules of Business.

" While we look forward to significant changes in the existing constitutional and legal provisions on the basis of the recommendations made by the Constitutional Reforms Commission set up by the interim government, it is very likely that the Westminster model of government will continue with necessary provisions for de-concentrating of power as well as adequate checks and balances. Experiences suggest that although we had a Westminster model of government in books, it was a prime ministerial system of government in practice, as many would argue, and not a cabinet or parliamentary form. It was customary for the chief executive of the government to make critical decisions individually instead of jointly by the cabinet.

The existing provisions for in-depth consultations with relevant stakeholders from within and outside the government were also not properly followed. In this situation, in many cases, they were hardly collective decisions, and in the absence of collective decisions, the concept of "collective responsibility" becomes irrelevant. It is also interesting to note how members of the same cabinet occasionally spoke in public on important policy issues very differently.

"Rules of Business" provides that ministers shall act as official spokesmen of the government in respect of their ministries. Secretaries and other government-authorised officers may also act as official spokesmen. No statement involving foreign policy shall normally be made by a person other than the prime minister and the foreign minister without prior consultation with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs [Rule 28 (4)].

However, we have noticed multiple ministers making public statements on issues with serious foreign policy implications, sometimes in an inconsistent manner. The concept of collective responsibility does in no way waive the minister's personal responsibility with respect to leading his or her own ministry. According to the "Cabinet Manual" mentioned earlier, ministers remain accountable to the parliament for decisions made under their powers.

The "Ministerial Code" of the UK government further elaborates that the minister in charge of a department is solely accountable to parliament for the exercise of powers on which the administration of that department depends. Bangladesh's "Rules of Business" also states that subject to other relevant provisions, all business allocated to a ministry/division shall be disposed of by, or under the general directives of the minister-in-charge. The minister shall also be responsible for conducting the business of his ministry/division in the parliament.

As administrative head and principal accounting officer of the ministry/division, the secretary is responsible for careful observance of relevant rules and regulations with regard to administrative and financial matters. The secretary is also required to keep the minister informed of the workings of the ministry/division [Rule 4]. It may be noted that a minister cannot disown the stance of his ministry with regard to important policy or executive decisions.

He cannot be bypassed in submitting a proposal to the cabinet or the prime minister. The standard last paragraph of a summary for the cabinet or a cabinet committee is, "The minister in charge of the Ministry X has seen the summary, approved it, and given his consent to send it to the Cabinet Division for consideration of the Cabinet/Cabinet Committee on Y" and signed by the secretary. Summaries to the president and the prime minister are also submitted through the minister.

The idea of a minister's individual responsibility occasionally raises scepticism mainly on two grounds. First, whether a minister can be held responsible for any failure or mistake given that in a Westminster model, government decisions entail collective responsibility. In this context, one needs to differentiate between the decisions made by the cabinet and by the line ministry.

The "Rules of Business" categorically mentions that no important policy decision shall be taken except with the approval of the cabinet [Rule 4]. It also provides an indicative list of cases that should be brought before the cabinet [Rule 16]. Other matters are decided by the respective ministries for which the minister is responsible.

Here comes the second reason for being sceptical about the minister's individual responsibility. In reality, a minister is not involved in deciding on each and every case. Much of the authority in a ministry is delegated to various levels of the bureaucracy.

In this context, how can a minister be held responsible for an action taken without his approval or even knowledge? Whether a minister should step down, taking responsibility for the fault of his colleagues, is an old, unsettled question. Where a wrong action has been taken by a civil servant that the minister disapproves of and has no prior knowledge of, he is still responsible to parliament for the fact that something has gone wrong in the ministry or department, and he alone can tell parliament what happened. In 1954, the UK Minister for Agriculture, Sir Thomas Dugdale, told the House of Commons, "I, as a minister, must accept full responsibility to Parliament for any mistakes and inefficiency of officials in my department, just as, when my officials bring off any successes on my behalf, I take full credit for them.

" The minister chose to step down, although the prime minister defended him. According to the UK "Cabinet Manual," civil servants are servants of the Crown. The civil service supports the government of the day in developing and implementing its policies and delivering public services.

Civil servants are accountable to ministers, who in turn are accountable to parliament (7.1). The manual further states that ministers also have a duty to give fair consideration and due weight to informed and impartial advice from civil servants, as well as to other considerations and advice in reaching policy decisions (7.

2). The same provisions are echoed in the UK "Ministerial Code" (5.1, 5.

2), which also defines the role of heads of departments and the chief executives of executive departments who are appointed as accounting officers (5.3, 5.4, 5.

5). This is similar to the provisions for the secretaries acting as principal accounting officers in Bangladesh's "Rules of Business." The introspection of Sir Winston Churchill, the British prime minister during the Second World War, about the fall of Singapore to the Japanese forces is still useful in understanding responsibility in the context of government.

He wrote, "I ought to have known, my advisers ought to have known, and I ought to have been told, and I ought to have asked." The primary responsibility for a wrong decision or action lies with concerned officials, but the ultimate responsibility goes to the political leadership. While officials have a responsibility to provide proper advice proactively, the leadership needs to seek advice from those who know the matter.

This explains why the UK "Cabinet Manual" and "Ministerial Code" attach so much importance to acting on informed advice. In the Westminster system, the collective responsibility of the cabinet is critically important for making coherent and integrated policies and their effective implementation. It also helps mitigate the excessive concentration of power in the hands of the chief executive and makes the decision-making process more participatory and inclusive.

This holistic approach is strengthened by individual ministerial responsibility and bureaucratic accountability. Wider and deeper consultations with stakeholders are crucial for the system to perform better. Eventually, they become instrumental for public institutions to fulfil the government's obligations to the citizens.

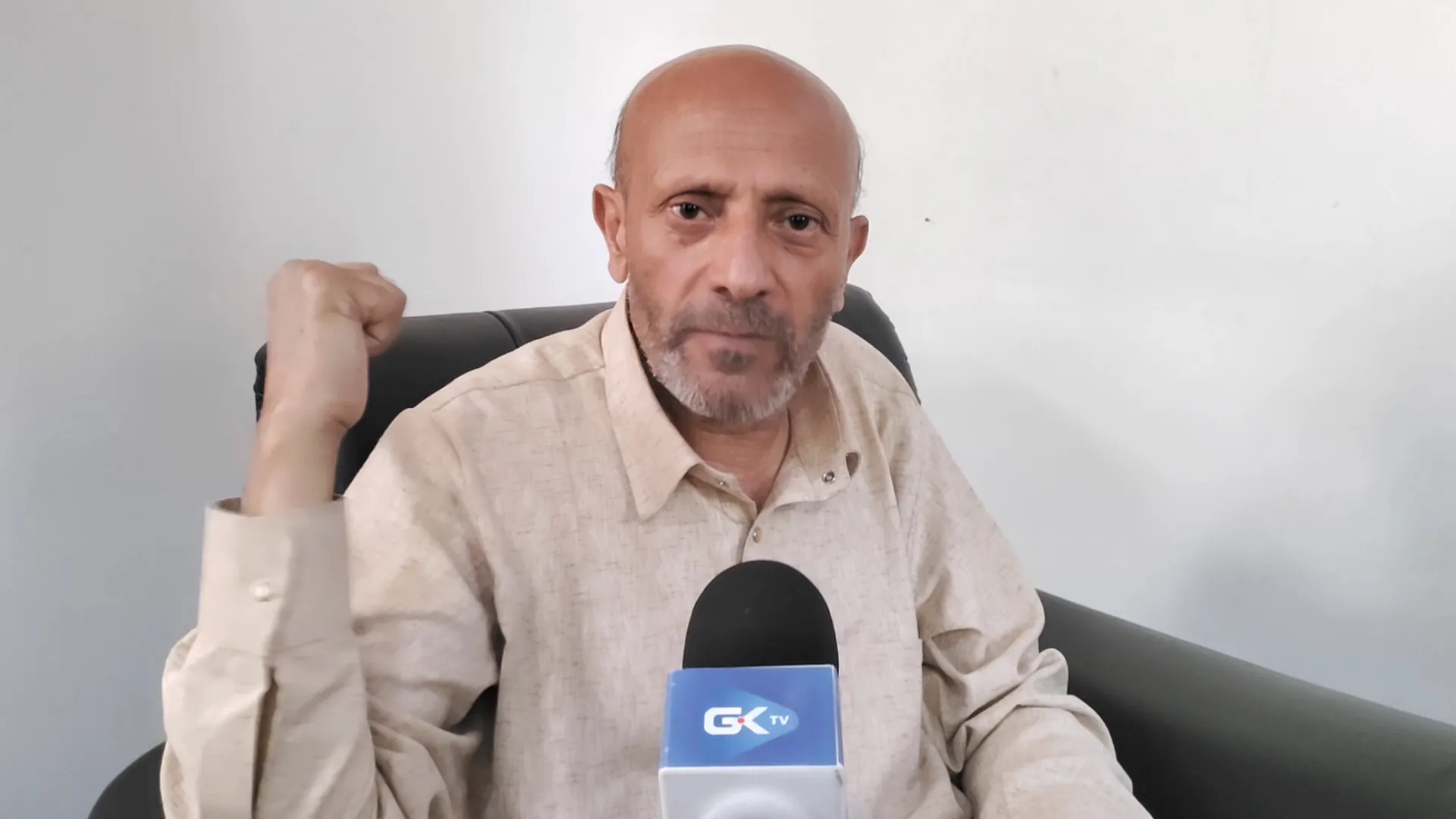

M Musharraf Hossain Bhuiyan is former cabinet secretary, Government of Bangladesh, and currently serving as senior adviser at the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD). Views expressed in this article are the author's own. Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals.

To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission..

.jpeg?crop=1200%3A800&height=800&trim=0%2C4%2C0%2C4&width=1200)