One of the quiet achievements of the Turnbull and Morrison governments was the reform of the family courts. Family law is always a vexed issue. Because about one in every three marriages ends in divorce, it is the area of the legal system with which Australians are most likely to have experience – either directly, or through a close relative or friend.

While there is nothing that governments can do to eliminate the emotional trauma of family breakdown, they can at least ensure the legal system that deals with it doesn’t make it worse. At the very least, they can ensure the courts are designed to mitigate two of the greatest sources of distress: cost and delay. This was the purpose of a series of structural reforms begun by Malcolm Turnbull’s government, and carried to completion under Scott Morrison’s.

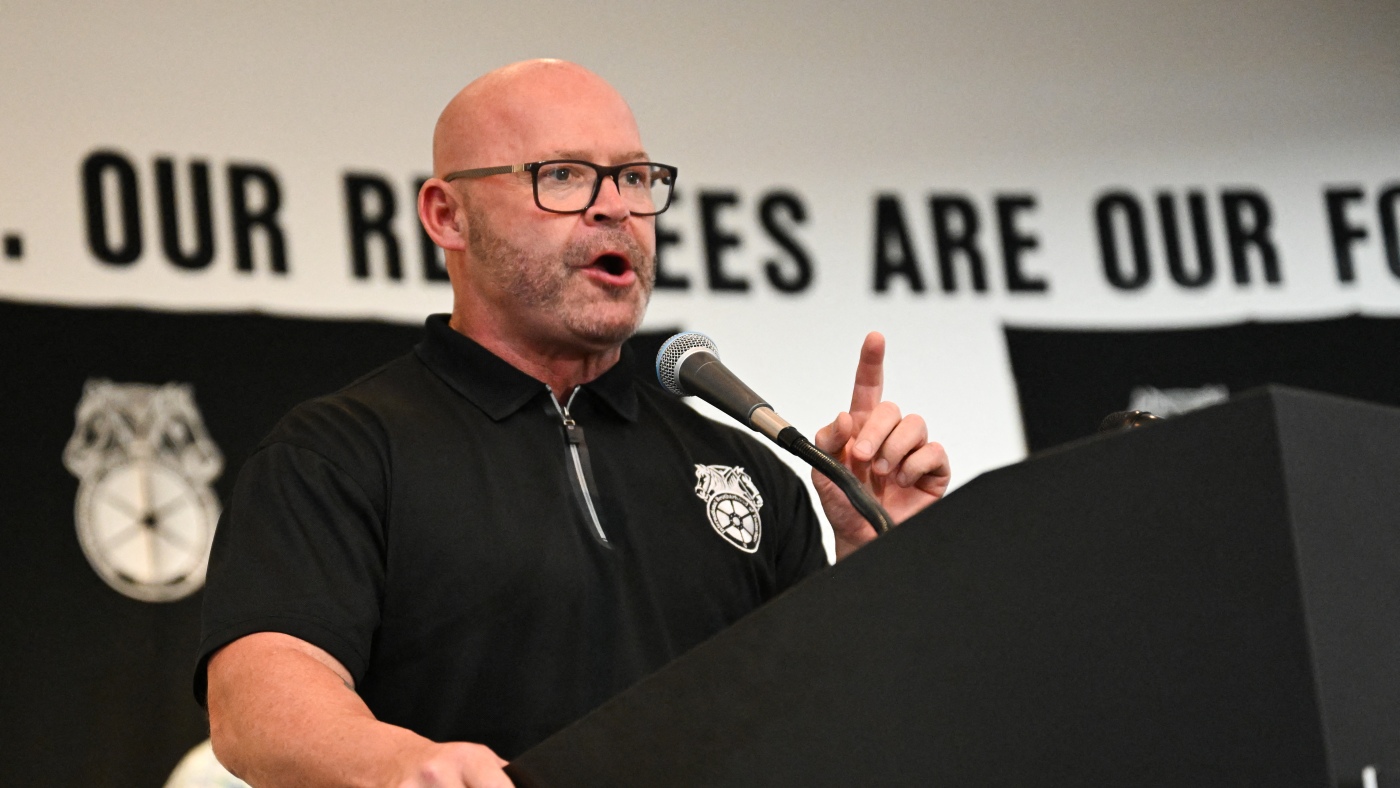

George Brandis, then attorney-general, with (left) John Pascoe and (right) William Alstergren in Canberra on October 12, 2017. Credit: Andrew Meares The key to the reforms was the restructure of the court system. Previously, two different courts – the Family Court and the Federal Circuit Court – had dealt with family law matters.

Obviously, having two different courts administering the same laws led to overlap, jurisdictional confusion and delay. As Chief Justice William Alstergren said in his keynote speech at the No To Violence conference last week: “Four or five years ago, the courts were not in the position they are now to properly meet the needs of Australian families. .

.. [T]he courts were exercising almost identical jurisdiction, but with different rules of court, different case management processes and procedures, conflicting court forms and websites, and sometimes different names for the same basic parts of court administration.

” Through the consolidation of the family law system into a single court – the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia – jurisdictional confusion and duplication were eliminated, while delay and cost were significantly reduced. Structural change alone, however, is never enough. To ensure the benefits of the reforms were achieved required dedicated judicial leadership.

With the upcoming restructure in mind, I recommended to cabinet Alstergren’s appointment as chief judge of the then Federal Circuit Court. Both as president of the Australian Bar Association, and subsequently as chief justice, he has shown himself to be a skilful leader. Importantly, as his principal area of practice had not been family law, he was not part of the self-serving club which had, for years, resisted reform.

Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus has announced a review of the family court system. Credit: Alex Ellinghausen Alstergren replaced John Pascoe, who became chief justice of the Family Court upon the retirement of the incumbent in 2017. Pascoe, a quietly spoken man who has devoted much of his life to such causes as the elimination of child slavery and improving access to justice for Indigenous Australians, brought immense moral authority to the role.

As chief justice, he laid the pathway for reform, often in the face of intense institutional resistance by some judges who were more than comfortable with the status quo..