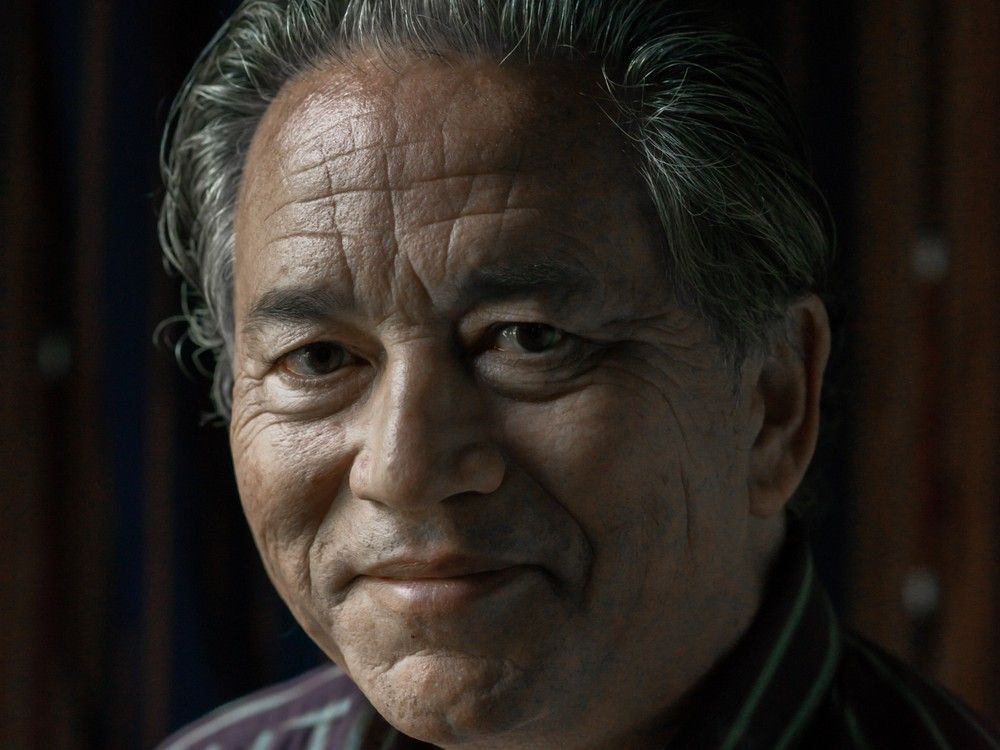

Friends, family and readers are feeling the gap left by an Alberta luminary on the Canadian literary scene. Treaty 8 Cree author Darrel J. McLeod died on Aug.

29. Many people have reached out to his family, said nephew Joey Schroeder. “It’s been overwhelming,” he said in a phone interview.

McLeod, 67, had been hospitalized for two days before passing away from a sudden illness. A true renaissance man, McLeod had been healthy and active, running and going to the gym, and he had just completed the Mamaskatch Jazz project with a concert at Beacon Hill Park in Victoria, his nephew said. “He had a beautiful jazz voice, very soft and elegant.

And when he needed to hit a note, he hit it.” McLeod, who hails from the hamlet of Smith in northern Alberta, made two recordings, “and we’ve been listening to them pretty much non-stop,” Schroeder said. After McLeod’s sister died when her son Joey was six, the writer became a father figure to his nephew.

“He was like a guiding light to me all my life,” Schroeder recalled. “We had lots of fun together, lots of singing, lots of cooking. He was always there for my four kids.

He was a wonderful man, and anytime I needed anything or help or guidance, he was there. “Love is his biggest legacy. He had so much love for everybody, and he wore it on his sleeve.

“And he never put up with any bull—-, which was another thing I admired about my uncle. He always stood up for people.” McLeod’s 2018 best-selling memoir titled Mamaskatch: A Cree Coming of Age, was a frank and nuanced account of a childhood fraught with the perils of physical and sexual abuse and the impacts of the residential school system.

It earned him the Governor General’s Award for English-language non-fiction. McLeod worked in education and health care, then as a land claims negotiator and director of education and international affairs for the Assembly of First Nations, eventually heading an Indigenous delegation to the United Nations in Geneva, according to his publisher. He studied at Simon Fraser University’s The Writers Studio with Oscar of Between author Betsy Warland, where he began crafting Peyakow: Reclaiming Cree Dignity, A Memoir.

“By reconnecting stories torn apart by poverty, tragic deaths, racism, homophobia and bureaucratic white privilege, McLeod performs a sacred act,” Warland wrote. Jake Cardinal of Alberta Native News called Peyakow “an epic tale of one man’s journey to find his culture and to help his people.” “McLeod carries the emotion found only at the end of life through each scene and sentence to create a cacophony of first-hand, Indigenous experience,” Cardinal is quoted on the D&M website.

Francine Cunningham is an Edmonton-raised Cree-Metis writer now living in Strathmore. The author of God Isn’t Here Today she met McLeod at the Banff Centre for the Arts where they were in residency. “He was always very kind, always smiling, always laughing.

He was always a cheerleader. Anytime I posted any good news about anything I was doing, he was one of the first people to comment, to say, ‘Way to go! Looking forward to reading anything that you write,’” she told Postmedia. “He was basically like the CanLit cheerleader, always willing to share posts of other people, of what they were doing.

Positive energy — only positive.” Queen’s University Chancellor and former CBC Next Chapter host Shelagh Rogers remembers McLeod as an interviewee and friend. “He brought that aura of kindness, although he didn’t suffer fools, and he could be righteously angry about things,” she recalled.

“On my Facebook post, I called him love on legs. He walked in love the way some people walk in beauty, and he was so generous with it. “He always led with kindness and love.

” Rogers said McLeod was a great storyteller. “If you’re going to be a memoirist, you have to be open about what you’re writing about. And he was,” she said.

“He had such a strong authorial voice, and he was proud of who he was, he was really proud of where he came from. He was proud of where he’d gotten to in his life, and the activism he had done, and how that crossed-stitched with his writing so beautifully.” She last saw him when his novel A Season in Chezgh’un came out.

“I can’t believe it’s the last time, because, of course, you always think there’s more time,” Rogers said. Now that he’s gone, she sees the epigraph from Peyakow coming to life. “’Love is something that you can leave behind when you die.

It is that powerful,’” she said, quoting the words of Lakota holy man John Fire Lame Deer. “(McLeod’s) spirit of love will go on and on and on. I’m so glad we have three of his books, because all of his stories will go on and on and on,” Rogers said.

“He’s just an amazing force, and that force hasn’t gone.”.