The youth in Britain has been plunged into a ‘happiness recession’, according to well-being experts. Mental health has become a growing concern among teenagers in the U.K.

for some time now, impacting their school participation and overall well-being. That problem has become especially dire among teenagers. British 15-year-olds have reported the lowest life satisfaction compared to their peers in other parts of Europe, according to the Children’s Society’s 13th annual children’s well-being report .

The study published Thursday asked over 2,000 10 to 15-year-olds how they feel about family, friends, school and more to gauge their overall happiness. It also uses data from the latest U.K.

Longitudinal Household Study and OECD’s program to evaluate educational systems (called PISA) to draw comparisons. The charity found that a staggering number of youngsters in Britain are struggling—25% of the 15-year-olds surveyed reported low life satisfaction. That’s significantly higher than the European average of 16.

6% and the satisfaction seen among teenagers in the Nordics. For instance, only 6.7% of Dutch 15-year-olds said they weren’t satisfied with life, while 11.

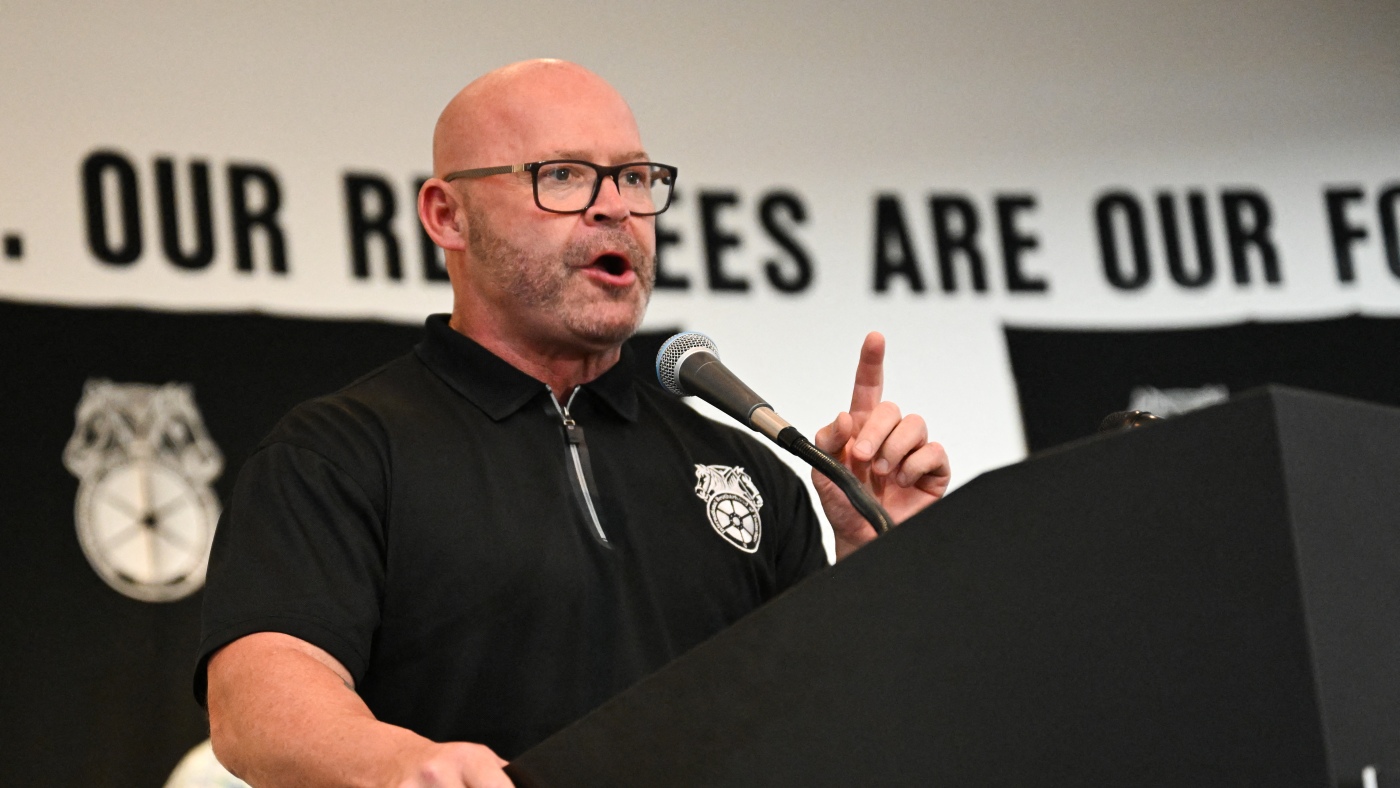

6% shared that sentiment in Portugal. “Alarm bells are ringing,” said Children’s Society chief Mark Russell. “U.

K. teenagers are facing a happiness recession, with 15-year-olds recording the lowest life satisfaction on average across 27 European nations.” Some of the youth’s concerns include the high cost of living and schoolwork.

The report noted that satisfaction levels had dropped sharply since the first report in 2009/10 on all fronts—whether friendships or personal appearance. The growing number of unhappy children could impact their well-being as they enter adulthood by limiting their ability to live fulfilling lives. This can manifest in various ways—school absences have been on the uptick .

Meanwhile, young workers have been taking more sick leaves than their seniors citing mental health reasons. This not only impacts productivity but also costs the economy hundreds of billions in lost output . More young workers are also economically inactive in the U.

K., attributed to mental disorders and lacking appropriate support services. A report by health insurer Vitality cautioned earlier this year that the U.

K. risked becoming a “ burnt-out nation ” as a result of the aggravating mental health crisis. These concerns have been observed globally and were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Young people in the U.S., for instance, are also the victims of a loneliness epidemic gripping the country.

The youth mental health crisis in the U.K. reflects the shortcomings of the country’s healthcare system and its accessibility for those in need.

Long NHS wait times and difficulty in getting support for children’s mental health crises have become alarmingly high—which Prime Minister Keir Starmer has acknowledged . The silver lining: children reported being most happy with their families, even though parents were struggling to find their financial footing. Historically, that metric has stayed consistent and could serve as a potential advantage for healthcare systems and policies to target through family support schemes.

The children of today will become the workforce and decision-makers of tomorrow. Addressing their needs and tending to their well-being could make or break the future..