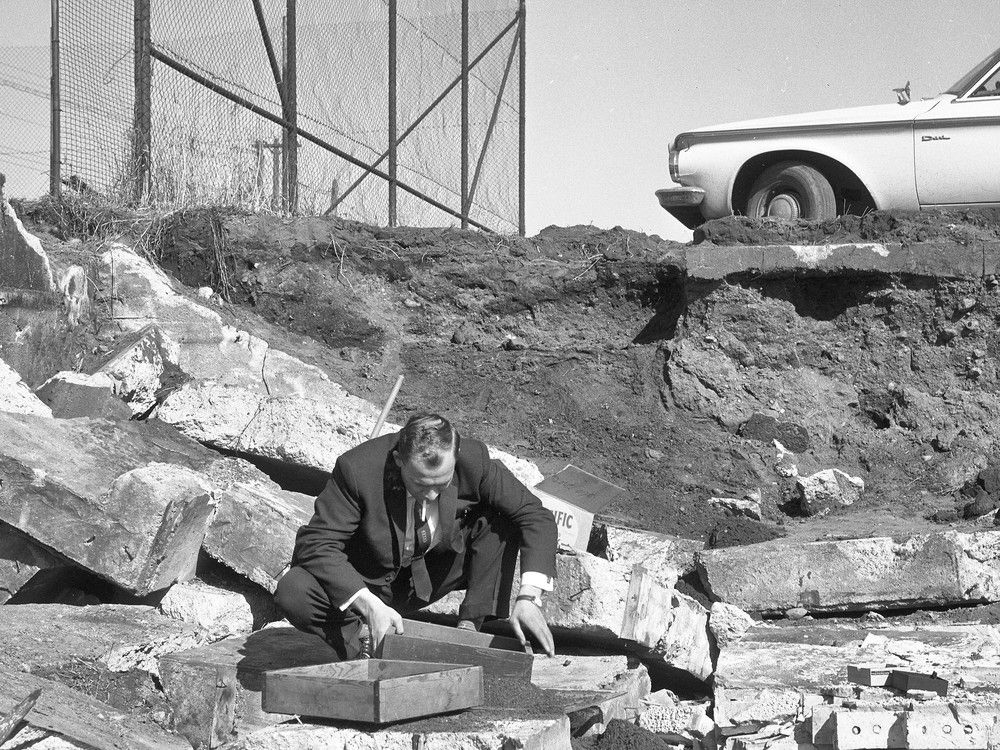

A Bangor resident last week replaced his slate roof with asphalt tiles — after city officials explicitly told him not to. Steven Farren’s home is in the Broadway Historic District, which requires him to get permission from the city to make changes that could alter the building’s exterior appearance, according to city code. On Nov.

14, 2024, Farren asked the city’s Historic Preservation Commission if he could replace the aging slate roof on his home with a type of asphalt that looks like slate, but is cheaper and more contractors are able to perform the work. After the commission told Farren no, he took the matter to the Bangor Board of Appeals on Jan. 2, where he was again denied.

But last week, Farren had his slate roof removed and replaced with the asphalt shingles that mimic slate anyway, bucking the city’s denials. In response, the city sent Farren a notice of violation on Wednesday, according to David Warren, a spokesperson for the city. It gives Farren a 30-day deadline for “fixing the violation.

” Farren told city officials that he intends to appeal the notice, Warren said, which would send the matter back to the city’s Board of Appeals. The stalemate between Bangor and Farren reveals how city rules can make purchasing and maintaining a historic home even more cost-prohibitive to some residents, particularly during a housing crunch. How the city responds could also set a precedent for other residents who want to alter their historic properties, and whether they will seek permission to do so.

Farren argued the city is burdening owners of historic homes by requiring them to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on a new roof because of “an antiquated rule,” he told the Bangor Daily News. “Overall, I think Bangor needs to do better so we can invest wisely into our historic homes instead of asking us to invest more than the houses are worth,” Farren said Friday. “The wait time alone is unreasonable for these homes to be held to such a standard.

” David Szewczyk, Bangor’s city solicitor, did not return requests for comment. It’s unclear what would happen if the Board of Appeals denies Farren and he refuses to change the roof to slate within the 30-day window. After “chasing leaks” in his slate roof for years, Farren wanted to replace the roof with asphalt tiles for two reasons: it’s more affordable and more contractors can perform the work in a shorter period of time.

Asphalt tiles cost $600 to $850 per square foot compared with slate roofs, which cost roughly $2,500 per square foot, Farren told the Bangor Board of Appeals in January. At that price, Farren said replacing his roof with a new slate one would cost him “well over $200,000, which isn’t economically possible.” Farren told the Historic Preservation Commission in November that the slate roofing contractors he spoke with were unwilling to give him a final cost estimate for replacing his slate roof.

Instead, the contractors only supplied starting estimates, which ranged from $125,000 to $140,000. The seven repairs that were already made to his slate roof each cost between $3,000 to $4,000, Farren said. Additionally, there are very few contractors in the state who specialize in slate roofs, and those who do have a waitlist of a year to a year and a half long, Farren told the BDN.

The slate roofing contractor Farren previously relied on, Walter Musson, died in 2019 . “This isn’t about money, it’s about reason,” Farren said. “There are new technological advances in roofing that are better, look just like slate and can be installed by any roofing contractor.

” The home was built in 1880 and Farren bought the property in 2017, according to city property records. The value of Farren’s home is currently assessed at nearly $472,000. During the November Historic Preservation Commission meeting, member Liam Riordan said the group’s role is to ensure any changes to homes in Bangor’s historic neighborhoods “preserve or enhance” the appearance of the building.

Removing a slate roof and replacing it with asphalt, in his opinion, does not preserve or enhance the home. Additionally, materials on historic homes should be repaired whenever possible rather than replaced, Riordan said. If an element must be replaced, the commission said it should be replaced with the same materials.

The roof needed to be replaced in full rather than repaired because a contractor told Farren that the slate tiles were “too brittle,” he told the Historic Preservation Commission. Farren’s insurance company agreed he needed a new roof to protect the home’s interior, as the roof was leaking in four places, he told the BDN. Farren believes his slate roof was installed after the Great Fire of 1911 — which his home survived — making it more than 100 years old and well past the 75 to 100 years slate roofs usually last, he said to the Board of Appeals.

At the time of the Great Fire, many homes in the area had cedar shakes, Matthew Weitkamp, a member of the Historic Preservation Commission, said in the November meeting. Many of the city’s slate roofs were installed after the fire as a way to protect homes from another fire. In the case of Farren’s home, slate tiles were laid over the cedar shakes, he told the city’s appeals board in January.

After Farren made his request to the Historic Preservation Commission, employees from Bangor-based Blackstone Restoration — which specializes in slate roof repair and is owned by Weitkamp — gave a presentation on the merits of slate roofs. The employees said they’re in favor of using slate because it’s a natural material, more durable than asphalt and is “serviceable” because crews can replace only the tiles that are broken, if needed. Weitkamp later told the Board of Appeals that he didn’t ask them to make a presentation on the benefits of slate roofs.

After he was denied, Farren pointed to the numerous homes around him, which are also in the Broadway Historic District, that likely once had slate roofs but now have asphalt roofs and never asked the city for permission. “I made the mistake of asking to replace the roof on my house rather than just doing what everyone else does and doing it without consequences,” Farren said. “It seems we’re being punished for trying to do things the right way.

” The Broadway Historic District contains dozens of properties and is one of nine such historic areas in Bangor, according to a city map . In the five years Liam Riordan has sat on the Historic Preservation Commission, the body has never allowed a property owner to replace the slate roof on their building with asphalt, he told the Board of Appeals. Riordan is aware of only one building that has been allowed to replace its slate roof with asphalt — the Bangor Waterworks Building.

That was allowed because the building isn’t in a historic neighborhood and was in otherwise poor condition, he said in January. After receiving the city’s violation notice, Farren said he’s not concerned about what action the city could take against him for replacing his roof with asphalt. Instead, he said his concern is preserving his home so that it remains structurally sound and beautiful.

“A precedent has been set by the 23 properties on Broadway and West Broadway that already have asphalt,” Farren said. “I don’t know how that came to be, but no one has taken any action against those properties. I don’t see how it’d be fair for the city to take action against me.

” More articles from the BDN.