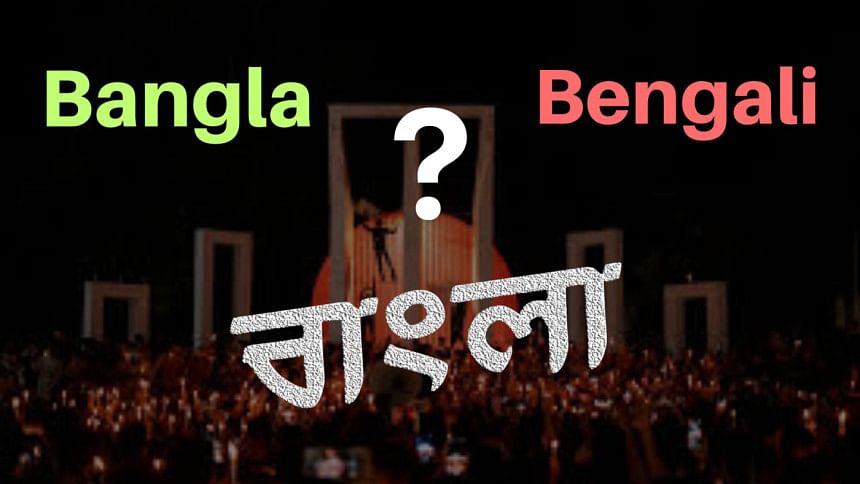

Bangla is what we native Bangalees call the language. And so that is what it should be known as. Just like Hindi, Urdu, or Tamil.

So why not use the word Bangla globally, instead of "Bengali?" After all it's a proper noun that can't really be translated. Besides this is not just any language. Bangla has a glorious past.

In fact, to show respect to our Language Movement of 1952, the International Mother Language Day is observed on February 21 or as we call it Ekushey February. Bangla enjoys the rare distinction of being a language that gave rise to a movement that ultimately paved the way towards a liberation war. Proponents will also point out that Bengali is derived from Bengal, which itself is rooted in the British colonial era anglicisation.

Surely, a language so steeped with the legacy of freedom should by all means seek to shed this burden and be known by its native name. That should be the end of the debate really. But not quite.

Languages have their own conventions and customs. Each language has its unique way of referring to countries as well as their languages depending on how the words evolved. For instance, Türkiye (pronounced tur-key-eh, or Turkey in English) is called Turoshko in Bangla.

England is Bilaat, and London we call Bilet! The language is Ingreji. We have adopted names of most other countries from the vocabulary of our colonial masters. It is always Ireland, Sweden, or Spain, never Éire, Sverige, or España.

We never say Deutsch or Français, but German and, perhaps, Forashi, if not French. And yes, those wiggly things do make a huge difference in pronunciation. But does this Banglicisation (or, if we insist on "Bangla," should it be Bangalification?—this brings up another point that we will get to shortly) of Français make any difference to the spirit of the French Revolution? Not adopting Ruuski and sticking to the Bangla Ruush, hardly erodes the magic of Pushkin's poetry.

Or does it mean we are being insensitive? Should the Swedes or the French take offence? On the other hand, however, if the French were to insist we retain their native name, it would be a nightmare for most to pronounce and we have not even broached the native languages of Africa full of clicks. But if others were to tell us how we should write the names of their languages and countries in Bangla, it would certainly rub us the wrong way. And more importantly, communication would become difficult.

We would not be able to convey which language or country we mean, without explanations and annotations, if one were to suddenly start referring to them by the native names deserting the customary ones. Another problem that arises from foisting a word upon another language is that it will entail invention of a whole new range of vocabulary. For instance, if it is Bangla, how do I express my Bengaliness? Or would it be Bangaliness or Bangaliana? Banglicisation or Bengalification? Do we then start saying, "O my golden Bangla" abandoning the age-old translation "O my golden Bengal?" Do the Sundarban tigers then become Royal Bangla Tigers? And what of the East Bengal Regiments or, for that matter, the Bengal Lancers from the colonial era? And let's not forget the "Bay of Bangla.

" But these are examples from the fringe. We really don't need to overthink it. So long as they call the language Bangla, we are happy, one might say.

But who are they? Perhaps, in our strong desire to shed the colonial anglicisation, we are rather fixated with the English terms. We are hardly bothered with what they call us in Mandarin, Kiswahili, or Russian. So long as we can set the English speakers straight and get them to say Bangla instead of Bengali, it would be considered a job well done.

Use of "Bangla" is indeed gaining more currency, especially in Bangladesh, although not as much on the other side of the border—India's West Bengal, where people speak the same language but still stick to the traditional English name—Bengali. The purpose of language is to communicate efficiently and towards that end, languages have a life of their own. They tend to adopt the most effective lingo as they gain currency or abandon words as they go out of fashion.

So long as people speak them, languages keep evolving. There are always different forces at play. The traditional pull factors and the youthful push factors together shape the course of languages.

Which is probably why, a Big Mac and a weekend are just "le Big Mac" and "le weekend" in France. But that is not a reason to let up and relent. Let "Bangla" be our little project.

We will keep pushing for it till we get everyone to say it right. Tanim Ahmed is digital editor at The Daily Star. Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission . Bangla is what we native Bangalees call the language.

And so that is what it should be known as. Just like Hindi, Urdu, or Tamil. So why not use the word Bangla globally, instead of "Bengali?" After all it's a proper noun that can't really be translated.

Besides this is not just any language. Bangla has a glorious past. In fact, to show respect to our Language Movement of 1952, the International Mother Language Day is observed on February 21 or as we call it Ekushey February.

Bangla enjoys the rare distinction of being a language that gave rise to a movement that ultimately paved the way towards a liberation war. Proponents will also point out that Bengali is derived from Bengal, which itself is rooted in the British colonial era anglicisation. Surely, a language so steeped with the legacy of freedom should by all means seek to shed this burden and be known by its native name.

That should be the end of the debate really. But not quite. Languages have their own conventions and customs.

Each language has its unique way of referring to countries as well as their languages depending on how the words evolved. For instance, Türkiye (pronounced tur-key-eh, or Turkey in English) is called Turoshko in Bangla. England is Bilaat, and London we call Bilet! The language is Ingreji.

We have adopted names of most other countries from the vocabulary of our colonial masters. It is always Ireland, Sweden, or Spain, never Éire, Sverige, or España. We never say Deutsch or Français, but German and, perhaps, Forashi, if not French.

And yes, those wiggly things do make a huge difference in pronunciation. But does this Banglicisation (or, if we insist on "Bangla," should it be Bangalification?—this brings up another point that we will get to shortly) of Français make any difference to the spirit of the French Revolution? Not adopting Ruuski and sticking to the Bangla Ruush, hardly erodes the magic of Pushkin's poetry. Or does it mean we are being insensitive? Should the Swedes or the French take offence? On the other hand, however, if the French were to insist we retain their native name, it would be a nightmare for most to pronounce and we have not even broached the native languages of Africa full of clicks.

But if others were to tell us how we should write the names of their languages and countries in Bangla, it would certainly rub us the wrong way. And more importantly, communication would become difficult. We would not be able to convey which language or country we mean, without explanations and annotations, if one were to suddenly start referring to them by the native names deserting the customary ones.

Another problem that arises from foisting a word upon another language is that it will entail invention of a whole new range of vocabulary. For instance, if it is Bangla, how do I express my Bengaliness? Or would it be Bangaliness or Bangaliana? Banglicisation or Bengalification? Do we then start saying, "O my golden Bangla" abandoning the age-old translation "O my golden Bengal?" Do the Sundarban tigers then become Royal Bangla Tigers? And what of the East Bengal Regiments or, for that matter, the Bengal Lancers from the colonial era? And let's not forget the "Bay of Bangla." But these are examples from the fringe.

We really don't need to overthink it. So long as they call the language Bangla, we are happy, one might say. But who are they? Perhaps, in our strong desire to shed the colonial anglicisation, we are rather fixated with the English terms.

We are hardly bothered with what they call us in Mandarin, Kiswahili, or Russian. So long as we can set the English speakers straight and get them to say Bangla instead of Bengali, it would be considered a job well done. Use of "Bangla" is indeed gaining more currency, especially in Bangladesh, although not as much on the other side of the border—India's West Bengal, where people speak the same language but still stick to the traditional English name—Bengali.

The purpose of language is to communicate efficiently and towards that end, languages have a life of their own. They tend to adopt the most effective lingo as they gain currency or abandon words as they go out of fashion. So long as people speak them, languages keep evolving.

There are always different forces at play. The traditional pull factors and the youthful push factors together shape the course of languages. Which is probably why, a Big Mac and a weekend are just "le Big Mac" and "le weekend" in France.

But that is not a reason to let up and relent. Let "Bangla" be our little project. We will keep pushing for it till we get everyone to say it right.

Tanim Ahmed is digital editor at The Daily Star. Views expressed in this article are the author's own. Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals.

To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission ..