LEWISTON — Voters in Lewiston rejected this year’s proposed school budget twice before passing it, feeling the budget increases were going to raise property taxes too dramatically for homeowners who are already reeling from other inflation-related costs. Many residents feared the increase in property taxes from the higher school budget could force some people out of their homes. Of the residents who rejected the Lewiston school budget this year, many called upon the state to increase its funding to schools and stop enacting mandates that can have a cost tied to them but are not backed by additional state funding.

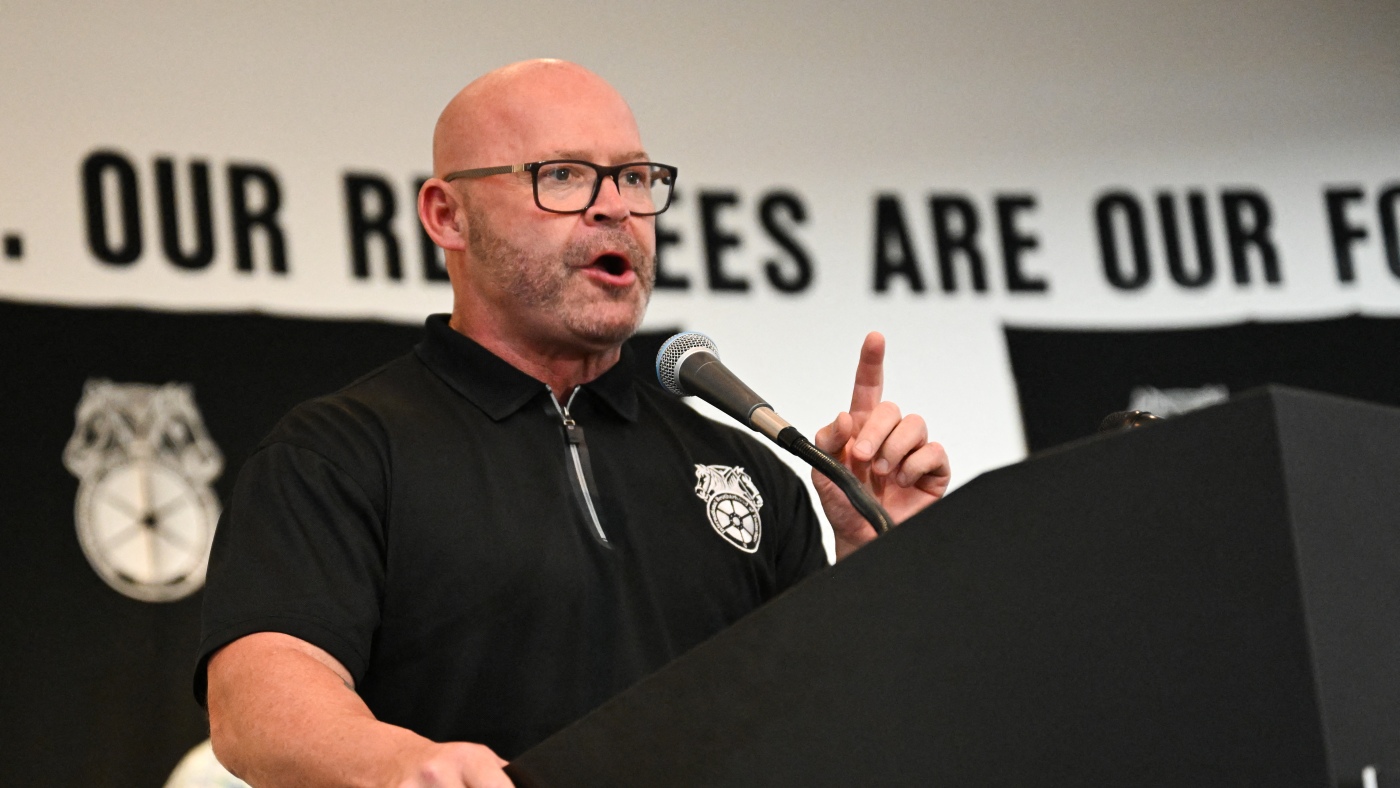

Lewiston Public Schools Superintendent Jake Langlais, seen July 22, would like to see less reliance on property taxes to pay for education and more federal funding. Daryn Slover/Sun Journal Lewiston Public Schools Superintendent Jake Langlais said recently he thinks placing so much funding responsibility for public education on local communities’ property tax is “cumbersome.” He said he would like to see more federal funding for schools that has fewer constraints on how that money is be spent.

“To fund (public education less burdensome to local taxpayers), you’d have to get to a place where you remove the property value piece, or if the property value is a component, it should be a qualifier, in that if you know that there’s lower property value or higher densities of disadvantaged (people) economically, that that becomes a factor in larger federal funding.” Those factors are considered in some federal funding to an extent, but it is not consistent and predictable enough, Langlais said. Further, federal funding is currently a small part of Maine school budgets.

Lewiston was not alone in struggling with its upcoming school budget. School districts based in Westbrook, Paris, Wales and Poland, among others, rejected their proposed budgets this year. Many school districts saw dramatic budget increases due to higher staffing costs and expiring federal emergency pandemic funding, along with other factors.

Traditionally public schools in Maine have been funded through a combination of state subsidies and local property taxes. Because of the substantial local property tax component, local school boards retain greater local control over local education, according to Ezekiel Kimball, interim dean of the College of Education and Human Development at the University of Maine. “That’s certainly a very important tradition in public schooling in general, in the United States and in particular in Maine, where the idea that a community should drive the decisions about what happens within the community’s schools is very much embedded in the fabric of the way that we make decisions about education,” he said.

In Maine, local property taxes often provide the largest share of funding for school districts, with state funding following close behind. Federal funds also contribute to school budgets, but at a much smaller rate. For the 2020-21 school year, 46% of school district funding in Maine came from local property taxes, while 39% came from the state, according to information on the National Center for Education Statistics website.

(These are the most recent figures comparing the rate at which schools are funded by state and local money in each state on the website.) Maine had the 11th highest rate of property tax income going toward school district funding in the nation during the 2020-21 school year, with New Hampshire, Connecticut and Massachusetts taking the top three positions, respectively, according to NCES data. For the 2020-21 school year, local property taxes made up 61% of funding for public schools in New Hampshire, 57% in Connecticut and 52% in Massachusetts, according to the data.

Maine’s school funding formula is complex and has several considerations built into it aimed at making state education funding more equitable across all school districts. The state determines a total amount of funding necessary to operate each district. It then subsidizes a portion of that, averaging statewide slightly over half of that total amount, with each local district responsible for most of the remaining amount.

Districts are free to raise more than that remaining amount if voters decide they want to spend more locally on education, which many do particularly in wealthier communities. The state’s complex formula to determine each school district’s base budget comprises multiple factors. It also uses that formula to determine how much of that amount the state will subsidize for each district.

While the average is about 50%, some districts, such as Lewiston’s, get a higher subsidy than other districts because of certain factors, including the number of disadvantaged students and English language learning students. The formula also takes into account small, isolated school districts, allocating more funds to them as well. The formula also determines how much a school gets for its gifted and talented program, special education program and transportation costs.

This formula is aimed to make education in the state more equitable while also maintaining local control over local education, Kimball said. However, some people have been critical of the formula and the state is currently examining the formula to determine if it is meeting its mission. “There is currently work ongoing in the state in order to determine whether the (Essential Programs and Services) formula does these things (and other adjustments) consistently with the policy’s goals,” Kimball said.

Despite the many factors weighed in the state’s school funding formula, an analysis indicates residents in Lewiston tend to be more burdened by local school budget costs compared to some smaller, wealthier communities. For instance, in Lewiston, the mill rate or property tax rate for the current school budget — the amount property owners are taxed per $1,000 of assessed valuation to pay for education — is $13.33.

Given the median value of owner-occupied homes in Lewiston is $189,500, that means an average residential property owner is paying $2,526 in property tax to support the education budget. Given the median household income in Lewiston is $54,317, according to the U.S.

Census Bureau, overall 4.65% of the average median household income in Lewiston goes toward funding education. In Falmouth, one of the state’s wealthiest communities, the town’s education mill rate for this year’s school budget is $9.

94. Given the median value of owner-occupied homes there is $609,500, that means the average residential property owner is paying $6,058 in property tax to support the education budget. Given the the median household income in Falmouth is $144,118, according to census data, overall 4.

2% of the average household income there goes toward local education. For the current school year, Lewiston Public Schools received most of its funding from the state, a little less than $73.2 million, which is nearly 80% of the roughly $85.

4 million base amount the state said the city needed to run its schools. Lewiston voters approved an additional $30.6 million to be raised through property taxes on top of that base amount.

In Falmouth, the state said it needs about $30.7 million to run its schools for the current year, with the state funding roughly $10 million of that. Residents voted to raise an additional roughly $40.

4 million from property taxation to fund the budget approved by residents. Ezekiel “Zeke” Kimball, professor and interim dean of the University of Maine College of Education and Human Development, said that in many cases, when states move away from local funding of education, it results in less local control. Contributed photo Lewiston’s large share of state school funding is mostly due to its high rate of economically disadvantaged students, which comprised more than half of its student body in the 2022-23 school year, according to data on the Maine Department of Education’s website.

The city also has a high rate of English language learners, a factor that also influences how much the city receives from the state under the funding formula. By comparison, Falmouth schools had a much lower rate of students in those categories during that school year. There are few popular funding models in the United States that move away from funding public schools by local or state taxes, according to Kimball.

There are many states in the United States that fund school budgets differently, but most tend to be a combination of federal, state and local property taxes. How much of those funds come from which level of government tends to vary by state. The federal or state government usually issues money and in return has certain expectations around staffing levels, types of curricular expenditures and other things, Kimball said.

“The main challenge is that when you get money either from the federal government or from the state government, it often comes with expectations about how that money is used, whether intentional or not, because of the way that that funding is granted,” he said. “..

. It has to be used in certain ways.” The power between local control and state control over education tends to teeter on how much of the school budget is funded by either source.

States where more of the funding comes from the state government tend to see less local control, whereas places where funding mostly comes from local property taxes tend to have more control over education in their district or city, Kimball said. All schools in the entire state of Hawaii are managed under one large state-based school district, along with all school funding coming from the state. Local governments are not allowed to raise money for schools through property taxation.

The single school board in the state formulates statewide educational policy and appoints executive officers in the public school system, public library system and members to the State Public Charter School Commission. The state’s school funding formula is based on a per-pupil cost, with a starting amount established per student and additional funds allocated on top of that for students who need extra support. Those funds are then given to schools based on student population.

If Maine were to move to a statewide school district, similar to Hawaii, it would require sweeping changes. Historically, there has been opposition to consolidating school districts, most recently in 2007 when Gov. John Baldacci signed a law requiring 290 existing school districts to consolidate into just 80, according to information on the University of Maine’s website .

Just five years after that policy was enacted, the number of school districts went from 290 to 164 by the 2011-12 school year. Many districts had not consolidated as was required, and a number of those that had consolidated wanted to dissolve. In 2022, Maine had 192 school districts, according to Ballotpedia .

Most public school funding in New Mexico comes from the state, with a smaller amount collected through property taxation. In New Mexico, 71% of school funding came from the state for the 2020-21 school year, while 14% came from property taxation that school year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics . The state allocates a certain amount of funding per student based on their level of need.

The funding formula gives the same funding to students in the same circumstances based on grade level, along with additional funding for other needs. The idea of giving all students in similar circumstances the same funding aims to equalize educational opportunities, according to information compiled by the state’s Legislative Education Study Committee. Schools have general discretion over how those state funds are used, but there are mandatory requirements and other factors that ensure schools are using those funds on priority programs and student achievement, according to the committee.

In the last year, state officials passed new rules implementing stricter requirements for schools, including requiring all school districts to have a minimum number of school days per school year — drawing criticism from local school officials over fear the measure erodes local control, according to a May 22 Santa Fe Reporter article . The most obvious barrier to funding Maine schools similarly would be determining where state funds would come from to fund that much of Maine schools’ budgets, Kimball said. The state could create new sources of revenue, it could cut state spending elsewhere and reallocate that to education, or it could shift funds raised by local municipalities to the state.

Vermont has a public school funding system in which much of the school budget is funded through local property taxes that are essentially collected by the state. Those property taxes are distributed by the state through its complex funding formula in an effort to better fund school districts equitably, according to information in the 2023 Report on Vermont’s Education Financing. Local school officials still develop a budget, which is then voted on by residents.

Each district has a set amount of state, federal and other predetermined revenues. Additional funding sources for educational costs not tied to property taxes include the state’s sales and use taxes, among others. These funding sources account for about 35% of education revenue, according to the report.

Remaining revenue must be raised through property taxes through a special tax rate set annually by the state legislature. The state’s funding system has been widely criticized. The state’s education property taxes increased this year in nearly every town, with some seeing a more than 30% increase on their property bill, according to an Aug.

14 article by Vermont Public. About a third of school budgets statewide failed to pass on the local level on the first vote. Maine used a similar model to fund education after the State Uniform Property Tax bill was passed in 1974, according to information on the University of Maine website.

It collected property taxes established by a specific property tax rate from all towns and combined that with state funds to be redistributed to schools. The model was unpopular among towns with high property tax bases, which tended to pay more into the system than they received for their local schools, according to the information. The legislation was repealed by referendum in 1977.

After the legislation was repealed, the state started providing a certain level of state funding to school districts using sources other than property taxes, with changes being made over the years, leading to the funding formula that is in place today. We invite you to add your comments, and we encourage a thoughtful, open and lively exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use .

You can also read our FAQs . You can modify your screen name here . Readers may now see a Top Comments tab, which is an experimental software feature to detect and highlight comments that demonstrate compassion, reasoning, personal stories and curiosity, and encourage and promote civil discourse.

Please sign into your Sun Journal account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe . Questions? Please see our FAQs .

Your commenting screen name has been updated. Send questions/comments to the editors..