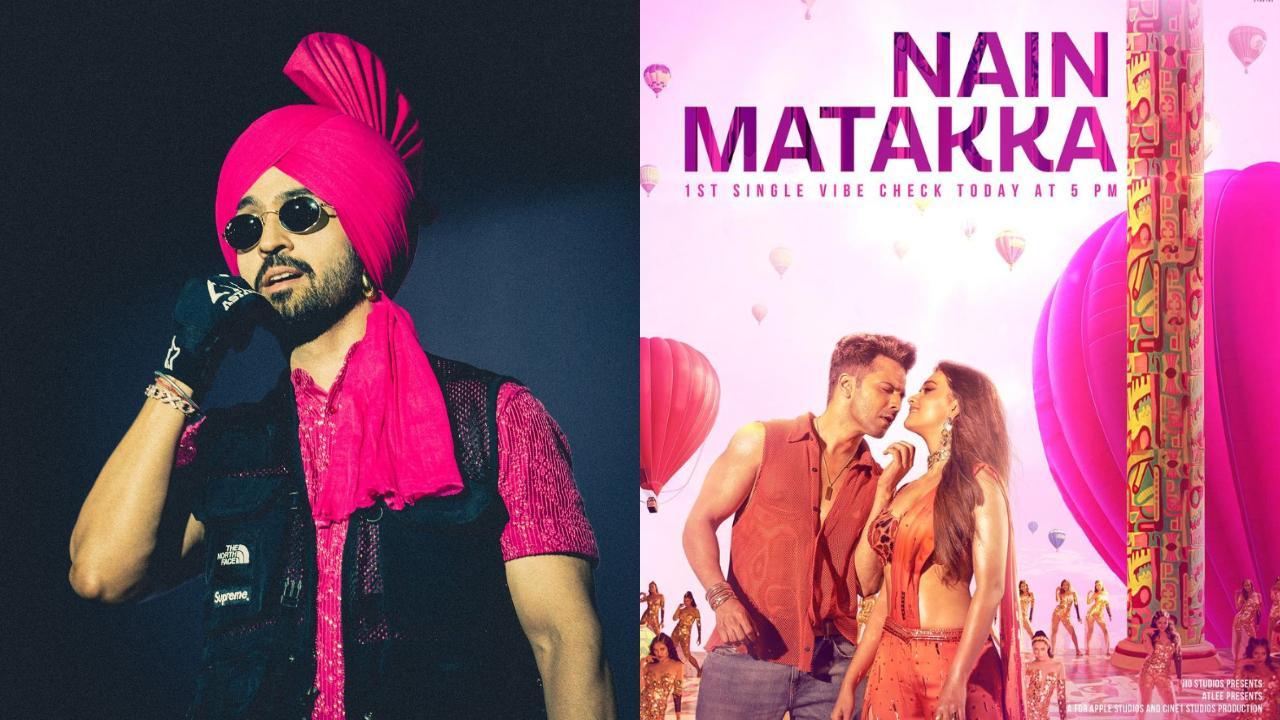

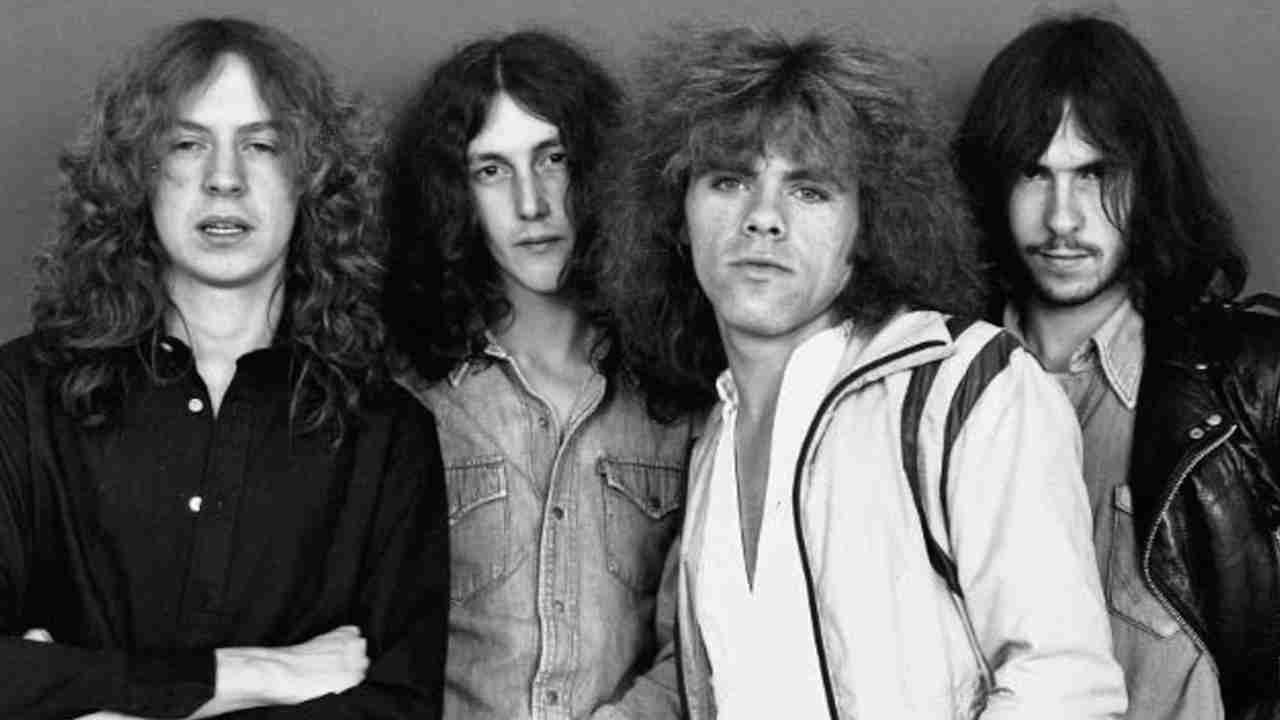

At the start of the 1980s, Diamond Head were being touted as rock’s Next Big Thing. They were dubbed the new by the more fervent quarters of the press, while others claiming their songs had more riffs than the entire Black Sabbath back catalogue. No other band from the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal era inspired more expectancy of greatness – and none suffered such a huge crash, as those aspirations disintegrated.

It all began in the Stourbridge area of the West Midlands in 1976, when school pals Brian Tatler (guitar) and Duncan Scott (drums) decided to put a band together. Joined by vocalist Sean Harris and bassist Colin Kimberley, the young foursome christened themselves Diamond Head, after the debut solo album from Roxy Music guitarist Phil Manzanera, . Their first gig was during February 1977 at a school in Birmingham, but their big break didn’t come until nearly three years later, when the band played two shows supporting , in Newcastle and Southampton.

As the NWOBHM wagon got up a head of steam, further gigs followed in the first part of that year with Iron Maiden and Pat Travers. Diamond Head were building a formidable reputation, gaining them a growing media profile. However, they were unable to convert all this momentum into a record deal.

Forced down the independent route, they released their debut seven inch single, / , through the small Midlands label Happy Face in May 1980. It was followed a month later by debut album . “We did the album off our own back, hoping to get a label to sign us,” says Brian Tatler.

“We’d already done the single, and then our management – Sean’s mum, Linda, and her boyfriend Reg Fellows – decided that we should record an album ourselves, and then try to get that deal. With hindsight that was a mistake, because record companies like to get involved in the studio, and not just get handed a finished product.” According to Tatler, Diamond Head spent a week at the end of 1979 in the Old Smithy Studios, Worcester, recording and mixing the album.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox! “We didn’t really need more time than that,” reckons the guitarist. “All of those songs had been really road tested – we’d done about 60 gigs by then, so knew them inside out. Those were our best songs, and it made sense to go with this list.

Sean and I effectively produced the album ourselves. There was an engineer there, a guy called Paul Robbins, but he didn’t have much of an input. We worked about 10 or 12 hours a day, so it wasn’t really all that pressurised.

” The finished album featured seven tracks, including from the single, plus , , the wired title track and the nudge-nudge wink-wink anthem , a song that barely bothered to conceal its double meaning. “I actually don’t know to this day what it’s about,” confesses Tatler. “Sometimes Sean would introduce it in our set as being about oral sex.

But then, I’ve also heard him go on about how it’s about the music business, you know, and the way they suck the lifeblood out of bands. Take your pick. It works both ways.

” But the album’s towering achievement was the seven-and-a-half minute , a slab of gothic-tinged metal that was Tatler’s attempt to match the bands he’d grown up listening to. “It took us about 18 months in all to get written to our satisfaction,” says Tatler. “It started off with me trying to beat the riff for Black Sabbath’s , which was my favourite riff.

I was determined to come up with something that was heavier. And, over a period of time, we kept adding bits and pieces, with Sean’s lyrics matching the evilness of the music. The last part was my guitar solo, which I wrote in the studio.

Little did we realise that this one song would actually feed and clothe us to this very day!” With finished, the band felt on top of the world. They’d even chosen that as the title “because it sounded so big”, according to Tatler. They were confident this would be their calling card to the big time – once labels heard it, the offers would come flowing in.

Except there was a problem. “We couldn’t get arrested,” says Tatler. “EMI and Phonogram dismissed us, because they had Maiden and Leppard.

And none of the others would touch us.” Snubbed by the major labels, the band decided to release themselves. The studio they’d recorded it in was owned by a guy named Muff Murfin, who also ran a label, Happy Face, which would put the album out.

“We pressed up 1,000 copies and sold them for £3.50 through mail order, and also at gigs,” says Tatler. The initial run of was memorably packaged in a white sleeve that was completely blank aside from a signature on each copy – no title, no band name, no tracklisting, no info on the label of the record, all which gave it the nickname ‘he White Album’.

A stroke of marketing genius positioning Diamond Head as an excitingly enigmatic band? Not exactly. The story goes that the band’s co-manager, Reg Fellows, owned a cardboard factory and was able to make the blank sleeves cheaply. “We didn’t have the funds to do artwork, so had to go for a bootleg look,” admits Tatler.

“That’s the truth. We were gonna have all four of us autograph every copy, but that would have meant doing 1,000 copies, which was way too much. We were too lazy, so in the end we agreed to do 250 each.

There was no big marketing game plan, or anything like that.” (A second pressing of 1, 000 was also printed up, only this time there was a printed label, giving it a bit more of a professional air). The band placed an advert in magazine, which ran for four consecutive weeks.

It was enough to conjure up a buzz. One of the copies of the album even made it into the hands of a teenage metal fanatic in Denmark named Lars Ulrich. “Lars wrote to us, and became a big friend,” says Tatler.

At the time, the future Metallica drummer’s fandom failed to help Diamond Head in real terms. Despite the quality of , it would be another two years before they finally bagged the major label deal they’d been seeking. MCA released their second album, (featuring a re-recorded version of Lightning To The Nations and Am I Evil?).

While it reached No.24 in the UK charts, it neutered all their epic virtuosity and power. Worse was to come with the following year’s Canterbury album, recorded with new bassist Merv Goldsworthy and drummer Robbie France, plus keyboard player Chris Heaton.

Fans didn’t react well to its attempts to change the Diamond Head sound, while its success was stymied by the fact that the first 20,000 vinyl copies featured a glitch that caused the songs to jump. The band were dropped by MCA the following year, and they fell apart soon afterwards, the promise they once had never really attained. But that wasn’t the end of the story.

In their absence, Diamond Head were held up as an influence by several bands in the emerging thrash scene. Chief among them Metallica, the outfit founded by Lars Ulrich, who would go on to record covers of four songs from : , , and, most famously, . Metallica’s version of the latter became so successful that many fans didn’t even realise it wasn’t one of their own songs.

“Am I hurt when I hear people refer to it as Metallica’s song?” says Tatler. “Not really. I’ve learnt to take this in my stride.

And, I have to say that the royalties we’ve made from Metallica covering has meant that Sean and I haven’t had to go back to our day jobs. If they’d decided to do another band’s song instead of that, then we would have found ourselves with some serious financial problems over the years.” Metallica’s run of Diamond Head covers spurred interest in the band.

Tatler and Harris reunited in 1990, and released a new album, 1993’s (featuring contributions from Black Sabbath’s Tony Iommi and Dave Mustaine of Megadeth). Despite a high-profile appearance opening for Metallica at the Milton Keynes Bowl in June 1993, the band fell apart. Tatler and Harris resurrected Diamond Head in 2000.

Harris left a couple of years later, but the guitarist has steered the band ever since with a cast of different singers and musicians. itself has been reissued and remixed several times over the years (repackaged with several different covers). Diamond Head still tour, and the songs from feature heavily in their set.

“I doubt Diamond Head could ever get away with leaving out, could we?” says Tatler with a laugh. might not have turned the band that made it into superstars, but it remains one of the most influential debut albums of the NWOBHM era. “I wish ‘Lightning To The Nations’ would have been the springboard to us making it big.

But it wasn’t to be. We got a lot of media praise, and all those comparisons to Zeppelin and Sabbath, which were a little embarrassing. However, it astonishes me that a record which sold so few copies in the first place can have made the sort of impact it has.

2025 Grammy nominations revealed: Metallica, Judas Priest, Spiritbox, Knocked Loose, Gojira, Pearl Jam and St. Vincent amongst metal and rock names nominated The 12 best new metal songs you need to hear right now “I remember knowing deeply it was a very special song”: Stone Temple Pilots’ Dean DeLeo on the making of their classic hit Interstate Love Song Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for magazine in the late 70s and in the early 80s before joining at its launch in 1981. His first book, , published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year.

Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the song in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. .

.