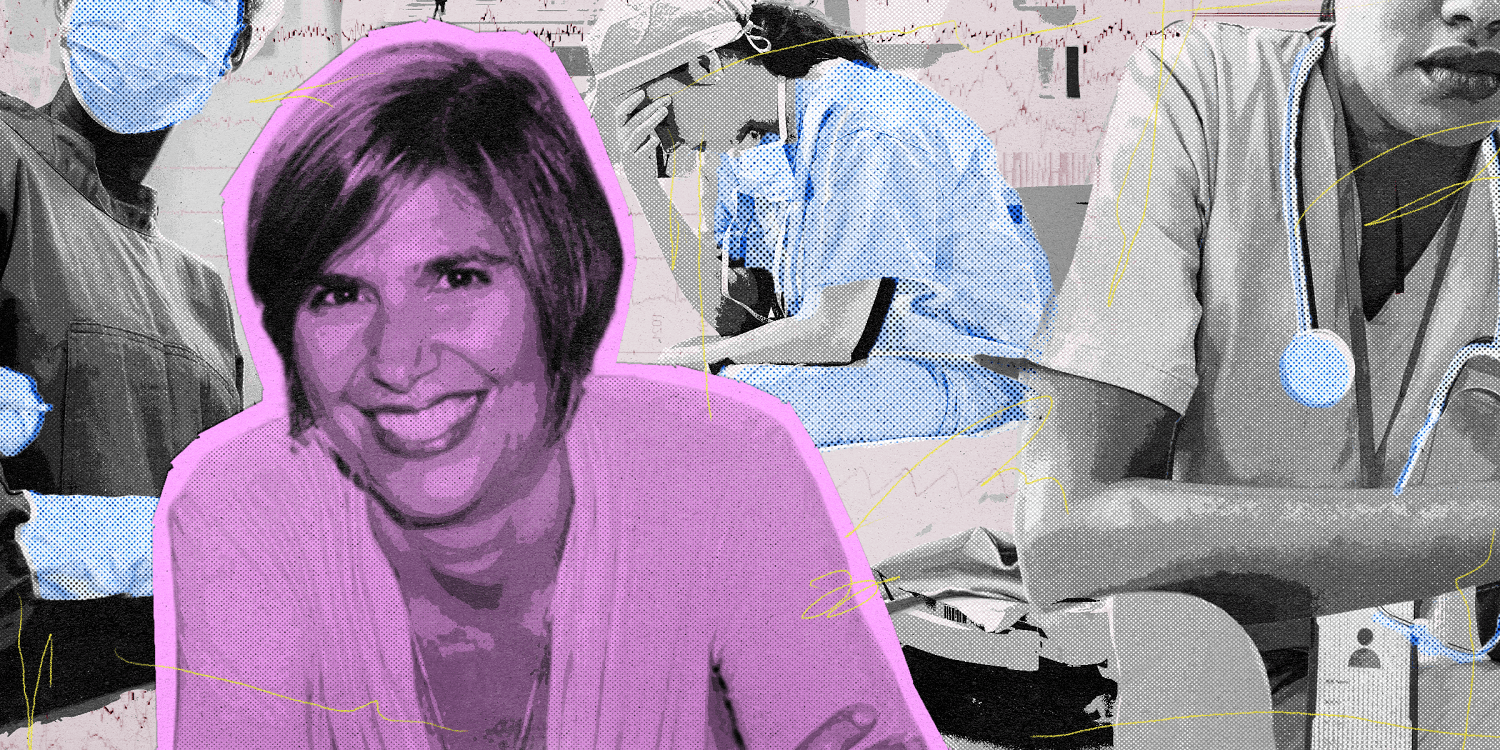

During her pediatric critical care training in 2023, Dr. Juliana Romano started feeling “pretty broken.” “I was coming to work and giving 100% of myself at work, but at the end of the day, there really wasn’t much left,” Romano, a pediatric critical care physician in New York City, tells TODAY.

com. “I was ..

. isolating myself from others, from activities that would normally bring me joy.” At the time, she didn’t realize she was severely depressed.

When she began to suspect something was wrong, she felt disheartened because she thought she couldn't receive treatment. Health care workers often hesitate to ask for mental health help, in part, because , research shows. “I had no hope of a future that included getting better,” Romano says.

“It was scary in the context of being a physician and wondering how that was going to impact my career and my co-workers’ ability to trust me.” The COVID pandemic has led to increased awareness of the mental toll of being a health care worker, especially after the , an emergency room physician at New York-Presbyterian Allen Hospital in New York City. Following her death, her family started a nonprofit, the Dr.

Lorna Breen Heroes Foundation, to support the mental health of health care employees and reduce barriers to obtaining treatment. While there have been some positive changes over the past five years, more still needs to be done, experts say. “Our ability to have this conversation in a very public way — even though (Breen’s death) crushed our family at the time — has really helped to normalize the conversation around seeking help,” Corey Feist, chief executive officer at the foundation and Breen’s brother-in-law, tells TODAY.

com. “We still have a way to go.” A from the U.

S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests that health workers' mental health has gotten worse since the pandemic began. Respondents were more likely to feel burnt out in 2022 compared to 2018, and they reported more harassment at work and a greater number of days where they had poor mental health, all of which can increase suicide risk.

also notes that physicians have a higher risk of suicide and suicidal thoughts than the rest of the population. In 2020, at the height of the pandemic, Dr. Lorna Breen, 49, felt overwhelmed by treating so many patients very ill with COVID-19.

Then, she contracted COVID-19 and grappled with depression. Her family knew that Breen felt as if she couldn’t ask for help. “She couldn’t stop working, and she certainly couldn’t tell anybody that she was struggling,” Jennifer Feist, Breen’s sister and Corey Feist’s wife, told .

“That needs to be a conversation that changes. People need to be able to say they’re suffering and to take a break." Romano, too, fretted about asking for help.

Luckily, her fellowship director noticed she was struggling and spoke with her. Romano says the interaction was "absolutely pivotal" in her getting the help she needed, adding that this positive experience makes her "an outlier, especially for people in health care." Romano's hospital also has a program that made it easy for her to access urgent mental health care.

"There are no doubts in my mind that this program and the providers that I was connected through it to ultimately are what saved my life," she says. Romano underwent acute electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for depression and took six months off. “Despite being a doctor and a medically savvy person, it still carried with it for me a lot of negative stigma,” she says.

“I felt like I was making this choice between my life and my career ...

I was deeply worried about its impact on my ability to be a doctor.” In reality, treatment helped her, and she was able to return to work. “I still see my same psychiatrist.

I am still involved in therapy,” she says. “Seeking help saved my life and therefore saved my career. In so many ways, it’s made me a better doctor.

” Back in 2015, Dr. Courtney Barrows McKeown refused to tell anyone about her mental health because she worried it could change her career dramatically. While in training, she began experiencing generalized anxiety disorder and started taking stimulants to keep up with her workload.

“I don’t have any ADHD,” the general surgeon from Tennessee tells TODAY.com. She thought, "Oh, I’ll just start taking something to make me get better.

’ I wouldn’t say no to projects. I thought I could pack more into the day." Over time, she needed to take more and more medication, which led to panic attacks and bouts of psychosis by 2017.

Even after being admitted to in-patient care, she wouldn't admit she was taking stimulants. But a urine drug test uncovered the substance use. Still, Barrows McKeown continued lying because she worried that needing treatment would prevent her from practicing medicine.

“Even my psychotic self honestly knew that part,” she says. “I was terrified.” Her training program connected her to a physician health program and psychiatrist, and she had to undergo monitoring to make sure she wasn't using drugs or alcohol.

Despite her sobriety, her mental health didn't improve. “I wasn’t really working a recovery program,” Barrows McKeown recalls. “I was doing the things I needed to do to be compliant with this monitoring agreement.

” In the next stage of her training, "a prestigious fellowship," she recalls that her mental health was “barely hanging on by a thread.” She was still being monitored, and in early 2021, one of her urine tests indicated alcohol in her system from the night before. Although she had not taken substances while seeing patients, the state she lived in required her test results be reported to the medical board, and her license was automatically suspended.

She was also dismissed from her fellowship. "I was terrified to tell my husband about what happened ..

. I was Googling a lot about physician suicide,” she says. She worked with her psychiatrist to create a safety plan and did six weeks of outpatient therapy.

After 90 days, she got her license back and got another job out of state. “I am leaps and bounds from where I was in 2017 and ..

. certainly in 2021 and even a year ago, honestly,” she says. She points out that if she had this experience more recently, she might've never lost her license and may've been allowed to enter a recovery program instead, as more state policies are allowing doctors to seek treatment.

“If you’re going to treatment ...

that same thing would not have happened today,” she says. Breen's sister and brother-in-law started the foundation because "we both committed that this would be worth doing if we could at least save a life,” Corey Feist says. Since the organization’s start five years ago, Feist has noticed some changes, such as more willingness among health care workers to have meaningful discussions about mental health.

But many employees still worry seeking treatment could hurt their careers. “Health care workers identify that the No. 1 reason why they don’t receive mental health care is fear of stigma,” Dr.

Stefanie Simmons, chief medical officer at the Dr. Lorna Breen Healthcare Heroes’ Foundation, tells TODAY.com.

“Licensed and credentialed health care workers (worry) that they will lose their hospital credentialing or their state licensing.” That's why the foundation launched its , which recognizes medical licensing boards and hospitals that don't require health care workers to report their full mental health histories, a standard practice before the pandemic. “That had a huge chilling effect on the willingness of health care workers to seek care,” Simmons notes.

“What we’ve seen over the past five years is a willingness of licensing and credentialing organizations to eliminate look-back questions from their applications so that health care workers are not being asked, ‘Have you ever been diagnosed or treated for a mental health condition?’” she explains. “Instead (it's), ‘Are you currently impaired in your practice for any reason?’ This is a big change.” Another initiative honoring Breen's legacy is the , signed into law in 2022 and up for reauthorization by Congress this year.

“The first iteration of the law impacted thousands of health workers,” Feist says. “It provided suicide prevention resources and training materials ..

. but it just began to make an impact on the lives of health workers, and we’ve got to extend it for five years. We are optimistic, but we need all the help we can get.

” Feist says that hospitals who have received grants hope “to continue to do the work,” while many others have asked for support. The nonprofit also launched aimed members of the health care community with the goal of further reducing stigma around mental health. It focuses on accessible, affordable care, privacy, increased training, and helping people return to work.

Some workplaces already embrace such measures, while others still are catching up. “Some health care leaders (understand) that the ability of their organization to survive relies on the professional wellbeing of the health care workforce,” Simmons says. “It’s my belief that those organizations will have a competitive advantage.

” Barrows McKeown and Romano also hope that more workers can start to see the benefit in prioritizing their own mental health. “In the last year or so, I made a lot of progress with (my mental health) and part of it was sharing my story, which helped eliminate a lot of the shame," Barrows McKeown says. Romano wants her story to encourage others to talk about their struggles and get help.

“It’s possible ...

to get the help you need and still have a really successful career, and it’s not going to impact who you are as a person or a physician,” she says. As Breen’s loved ones prepare to mark five years since her death, they say her legacy is reflected in the progress they're fighting for.“Lorna cared as deeply about the wellbeing of her colleagues and the students as she did about the patients she took care of,” Feist says.

“She would be most moved by the lives that we’ve heard that we saved.” Meghan Holohan is a digital health reporter for TODAY.com and covers patient-centered stories, women’s health, disability and rare diseases.

.